Ian Bell: England's Ashes hero puts fear of failure behind him

- Published

Fast bowlers you can duck. Spinners you can try to attack.

Form? Now there's the real frightener for a Test batsman: illogical and invisible; with you one moment, gone the next. And, when it inexplicably departs, as capable of reducing a man to rubble as any rampaging paceman.

"There are times when you don't even want to go to the ground," says Ian Bell, England's leading man as they fly to Australia, but in the past sometimes frozen in the spotlight. "It can be that hard.

"Can it change you as person? 100%. It can obsess you. It did in the early part of my career. There are times when getting to 30 feels a million miles away. And then suddenly you're in form, and getting to 30 just happens."

This summer, it just happened.

In 16 Test innings against Australia at home before the start of the year, Bell averaged 21. In six weeks this time around, he racked up 562 runs at an average of 62, equalling the English record for a five-match home Ashes set by Denis Compton back in 1948.

Why the transformation? Even in the preceding series against New Zealand he averaged just 18, with a top score of 31. What brought his mojo mysteriously back?

"We had a three-day training session at Loughborough before the Ashes," he says, sitting in the home dressing room at Edgbaston on a brisk autumn morning, "and something just clicked in the nets.

"It was only a slight technical thing - a slight backlift tweak - but because I'd spotted that thing, although I didn't have a lot of runs behind me, I went into the first Test feeling very confident.

"I got 26 in the first innings, under lights, in swinging conditions, and although it was only 26, I felt really good. I felt that was the best I'd played all summer.

"Suddenly it felt like a different game altogether."

Different game, different result. Without Bell's runs, England might have lost a series they went on to take 3-0.

"Gooch's training is about the physical as much as the technical: net sessions where each delivery is followed by 10 burpees, shuttle-runs between bouncers"

In each of those victories, Australia had a crowbar in the safe door: at Trent Bridge, with the hosts four down in their second innings and just 66 runs ahead; on the first morning at Lord's, with England teetering at 23-3; at Durham, when England lost their third second-innings wicket with the lead at just 17. On each occasion it was a Bell hundred that first saved the day and then set up the win.

If those cold stats were critical, the elegance of their assembly set him further apart. On low-scoring pitches where not one other England batsman got to within 20 runs of his average, Bell sometimes appeared to have twice the time to play his shots, and half the trouble timing them.

"Speed?" remarked Jackie Stewart, a few months after winning the first of his three Formula 1 world titles in 1969. "The whole business is the reverse of speed. Speed doesn't exist for me unless I'm driving poorly. Then things seem to be coming at me quickly instead of passing in slow motion.

"In form, I see things a long way off, in fine detail. A corner will come towards me very slowly… everything is clear, neither hurried nor distorted, like a slowed-down movie film."

Bell, a man whose delicate, caressing late cut sliced the Australian pace attack to pieces, nods in recognition.

"It's exactly the same for a batsman. When you're playing well, it feels as if the entire game has slowed down. You can pick the length that split second quicker.

"The late cut might look easy - well, when you're playing well, it feels like that. When you're out of form it feels quicker, and you look like that too - you're later into position, you're later with the shot. That's the difference with form. One tiny little thing, and you go from easy to rushed.

"But form, generally, is about outcomes. Runs. That's what people notice. And that can be frustrating, because as a batsman you might make 10, and think - that is the best 10 runs I've ever got.

"There's a certain confidence when you've got runs behind you. When you're searching for that big score, you sometimes try too hard. When you're playing well, not only does it look slowed down, but you allow things to happen. You don't go looking for it."

Not once in his big innings last summer did Bell look to be playing at anything other than the pace he wanted: not in his six-and-a-half-hour 109 on that low, slow Trent Bridge track, in compiling the same score in five hours at Lord's, or in making 113 off 210 balls to set up the win at Chester-le-Street.

Gilding the intense application was that gossamer late cut, a shot to make cricket aesthetes purr and turn the game's romantics weak at the knees.

Bell, who admits to trying to look too perfect a stylist as a kid, is aware of the spell it can cast. But it is rooted entirely in the practical - the prosaic solution to the most straightforward of cricketing sums. As spectators we might appreciate elegance as a discrete virtue. The professional, by definition, thinks only of results.

Bell was dubbed 'Sherminator' by Australia leg-spinner Shane Warne during the 2005 Ashes

"Goochie [England Test batting coach Graham Gooch] is always talking about hitting the gaps," he explains. "And that's what the late cut has been about - on the wickets that we played on last summer, it was more effective to let the ball come on to you and not try to hit it too hard. Whereas in Australia, on quicker pitches, the gap might be in front of square, so that's where you'd hit it.

"I know the late cut makes you look like you're in control, but it's not meant to be arrogant in any way. It's just the right shot for this wicket, against this bowling, on this ball."

The relationship with Gooch has been critical to Bell's ripening as a Test batsman, just as his old Warwickshire mentors Neal Abberley, Bob Woolmer and John Inverarity helped nourish the roots of his game.

Gooch being Gooch, it is about the physical as much as the technical: net sessions where each delivery is followed by 10 burpees, shuttle-runs between bouncers.

Bell has always oozed natural ability. Aged 14, he averaged over 100 for Warwickshire's under-16 side; two years later he was touring New Zealand with England's under-19s. But such latent talent is harnessed by the dedication of a self-admitted cricket geek. Bradman famously practised by hitting a golf ball with a stump; Bell, wherever he goes, takes with him a modified bat the width of a ball and another three-quarters as wide again.

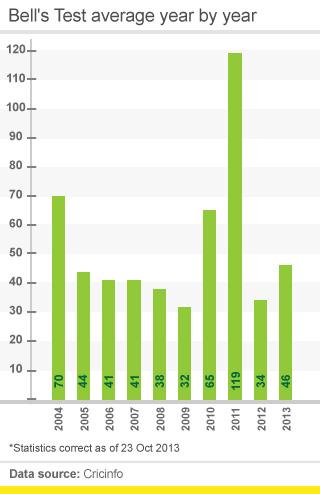

And it has taken time. You can split his Test career into three chunks: from debut to being dropped in 2006 (average: 39); his renaissance against Pakistan later that year to being dropped again early in 2009 (average: 41); and from his recall during the 2009 Ashes to the present day (average: 53).

"As a young player you concentrate a lot on technique," he says. "You prepare yourself technically, because you know you're going to get a certain number of balls that are going to challenge you around off stump, or lots of bouncers.

"But what I wasn't ready for was the mental side. And it was a bit of a shock to discover that's what top-notch cricket is all about."

There were times, in Bell's first Ashes campaign in 2005, when he looked like the new kid being picked on in the playground - surrounded, at the crease, by gum-munching bullies like Matthew Hayden, Ricky Ponting and Shane Warne, all hyena grins and relentless abuse.

Bell, famously dubbed 'Sherminator' by his cackling inquisitor Warne,, external smiles at the memory. "If someone has a go at you when you get out to the middle, be prepared for it. If someone ignores you, be prepared for that too. If it's a shock, if you can't cope with it mentally, then the technical battle is lost.

"Sometimes, when you're out there in the middle, it can be hard. If you look up at the dressing-room and there's no-one watching… It's 11 against one, most of the time. That's why it's important to bat as a pair. And as a team we talk now about 'balcony presence'.

"You need that mental method, just as you need the technical method, to be able to cope. Early in my career I didn't have that."

Like Stuart Broad, Jimmy Anderson and several other of his England team-mates, Bell prizes the input of team psychologist Mark Bawden. For this generation there are no hang-ups about utilising a profession that some older players, all stiff upper lips and manly silences, would have swerved as instinctively as they would a bouncer.

"I think he's been outstanding," says Bell. "He talks about this mental method, on and off the field. And just like having a batting or bowling coach, having someone who can help with that method is so important.

"When you come in as a young player, you want to impress everyone. You waste a lot of time trying to do a lot of things that aren't very important. There's no doubt that if I had a bad day I'd be thinking about it all the time, and if I had a good day I'd be right up.

"The skill - and you want to try to do it as early in your career as you can - is to be level. You want it so that people can't tell from you whether you've scored 100 or 10.

"That's the way to be in cricket because there are a lot of things that are outside of your control. Someone might bowl you an absolute jaffa. It takes time as a young player to learn that."

There is an equanimity to the 31-year-old Bell that was absent from the talented but timid tyro of a decade ago. He has his young family, although he will be on duty in Brisbane on his son Joe's first birthday. He has Gooch, and Bawden, and his team-mates.

Bell relishing Ashes challenge

"I've certainly got better at it over the years. I could still get better at it, because in cricket you always want to be perfect. But it's hard to be perfect. Bradman's the only one who's got close," he said.

"But as long as you've done everything you can, then if you get a great delivery, you can go home and be happy. The only time you don't feel like that is when you think, did I train hard enough, could I have been a bit fitter, could I have done more in the morning? Then it can eat away at you."

And what of that fickle companion, form? Does he fear it abandoning him during this winter's Ashes tour?

"There are obviously things technically you want to keep with you," he added. "The appreciation of your team-mates is where you get a lot of confidence from. If you know the dressing-room believes in you and backs you. It's about rhythm, and about confidence. And that comes from scoring runs.

"Before, while I had a good technical game, I didn't have a way of coping with the bad days. Now I've got more resilience about everything, to deal with the good and the bad days too."

You can hear the full interview with Ian Bell on Test Match Special this winter.

- Published23 October 2013

- Published26 August 2013

- Published25 August 2013

- Published11 August 2013

- Published11 August 2013

- Published25 July 2013