How beating cancer set Will Bayley on path to table tennis success

- Published

Paralympic silver medllist Will Bayley on beating cancer & opponents

Cancer is an undiscriminating destroyer of lives, yet Paralympic silver medallist Will Bayley feels he owes his career to the disease.

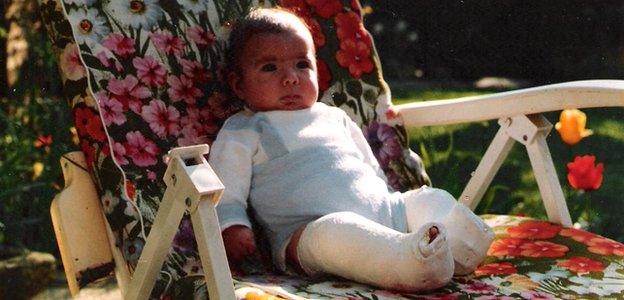

Born with arthrogryposis,, external which inhibits the movement of all four limbs, Bayley underwent 12 agonising bone-breaking operations as a child to re-shape his feet.

Then, at the age of seven when he and his family thought they were finally through the worst years, came the devastating diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, external.

"Chemotherapy was really tough, I went through a lot of pain and hardship as a kid and I kept having setbacks," Bayley told BBC Sport.

"I got infections, ulcers and had to keep going back to hospital. Sometimes I felt like giving up.

"At that age, though, I still don't think I understood just how bad it was. If I got it now I would probably freak out and be really scared!"

To help distract Bayley from the torturous treatment and aid his active rehabilitation, his grandmother bought him a table tennis set.

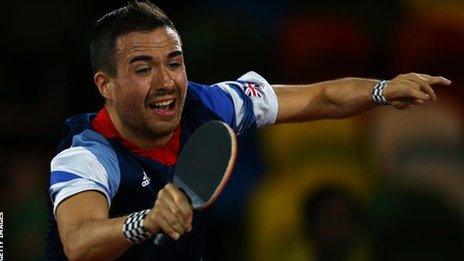

Fifteen years on, that path took him to the Paralympic podium in London where he collected individual silver and team bronze.

"It's weird really, it's like it was meant to be," he said.

"It's strange to think what I would have been doing if it wasn't for that [cancer], because table tennis is my life."

Bayley believes these experiences developed his "unrivalled winning mentality" - something he aims to utilise this week when bidding to retain the European crown he first claimed two years ago.

Will Bayley had to undergo 12 bone-breaking operations on his feet as a child due to arthrogryposis.

Gold medals and the pursuit of world number one status are a far cry from the struggles of his early years.

"We knew from a scan before he was born that his feet were really bad," said his mother Chrissie - who has a milder form of arthrogryposis.

"It was desperately heartbreaking because you would go through anything rather than see your child suffer."

The condition runs in Chrissie's side of the family, affecting her feet and her brother's hands.

"The only way they could get his foot flat was to pin and cement it to the floor," she said. "The next stage would have been to take off [amputate] from the knee down which would have been the worse possible scenario. Fortunately it worked out."

Due to his numerous operations, Bayley spent much of his childhood at London's Great Ormond Street Hospital, external, but visits became even more frequent in 1995.

A course of antibiotics to treat an 'inflammation' in Bayley's neck failed to remove a lump, but a subsequent second-opinion, scan and biopsy brought the correct diagnosis.

"We were asked if we wanted Will to be one of 10 children used as guinea-pigs where he would be given chemotherapy that had never been tested on children before," Chrissie said.

"They weren't sure of the long-term consequences to kidney, muscles around the heart and even puberty as it was a stronger dose - usually for adults - but we agreed to it."

Chrissie admits it was an "intense" six-months but that she always believed her son had the fight to come through the ordeal - even though he had the occasional doubt.

"We were just watching the television one day and he said 'I don't want to do this anymore,' but then asked me 'will I die if I stop?' and I said yes," recalls Bayley's mother.

"The next morning when I got up, he was already sat by the door with his bag packed ready to go [for treatment]."

Losing his hair was a difficult side-effect to the procedure for Bayley to cope with, but time in hospital offered some reprieve to the self-consciousness he felt in public.

"He was much happier when he got back to hospital because then he could take his cap off like everybody else so he fitted in better then than he did at school," said Chrissie.

Will added: "I quite enjoyed being in hospital, even though I felt awful at the time, because there were loads of kids going through similar things and we all played and painted together."

He was finally given the all-clear around 18 months after the initial treatment and began playing table tennis regularly.

It remained a hobby rather than a career until Bayley moved from his home in in Tunbridge Wells and joined the British disability table tennis team, external in Sheffield ahead of the Beijing Paralympics.

He was eliminated in the group-phase in China, but after learning to remove any 'showboating' from his game, he went on to claim his maiden European crown in 2011.

"I like entertaining the crowds and when I'm playing table tennis I want people to say 'wow, this is great' and enjoy watching me play," said Bayley, who spent two years studying at the 'BRIT School', external for Performing Arts.

"I understand now that the most important thing is winning and if I can entertain whilst I'm winning, that's even better."

Bayley's energetic and passionate celebration after winning his semi-final encounter in London became one of the iconic images of the 2012 Paralympics.

However, his emotions were a stark contrast to when he was denied gold by Germany's Jochen Wollmert.

"It was really tough to lose the final," admitted the 25-year-old.

"I respect Jochen, he's a great champion but I feel like I'm the better player and I'm now really hungry for success."

Bayley, who also claimed bronze as part of the GB men's team event, continued; "I always have that drive because I know how lucky I am to be here [after overcoming cancer].

"I want a gold in Rio," he concluded.

- Published12 September 2016

- Published21 September 2018

- Published13 September 2016

- Published26 September 2013

- Published31 August 2016