Why are Coventry City at their lowest ebb for nearly 50 years?

- Published

There was warm applause at half-time in Coventry's home defeat by Doncaster, the match that sealed City's relegation to the third tier of English football for the first time since 1964.

But it was for the appearance on the pitch of the Sky Blues' 1987 FA Cup-winning squad, and it came in sharp contrast to the boos that moments before had rung round the Ricoh Arena at the end of a first half bereft of ideas or energy.

Coventry's decline over the 25 years since Keith Houchen's spectacular diving header helped them to a 3-2 extra-time win over Spurs at Wembley has been a steady one.

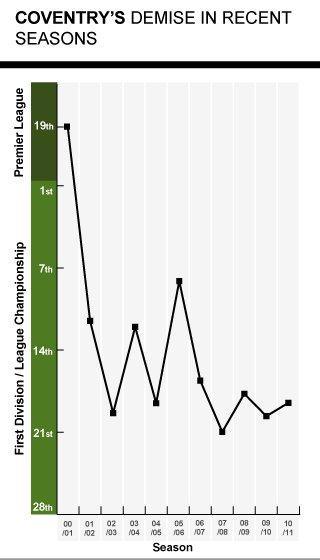

Since they were relegated from the Premier League in 2001, after 34 seasons in the top flight, the Sky Blues have never seriously threatened to bounce back - in fact, the team has not finished in the top six of any division since 1969-70. Tellingly, they are on their 10th manager in 11 years.

"I've never seen a bunch of players looking so jaded and spent as I did on Saturday," said Jonathan Strange, head of Coventry's London Supporters' Club.

Those are just the on-field problems.

Off the field, the club are heavily in debt, do not own their stadium, and are under a Football League transfer embargo for not filing their accounts.

"This is a crystallisation of years of mismanagement," added Strange. "The present owners [a hedge-fund called Sisu] underestimated the huge responsibility of taking over a football club."

And, according to Andy Turner, external of the Coventry Telegraph, it could get worse. "There is more talk of liquidation than administration," he said.

"Sisu are estimated to have spent £35-40m on the club since they took over in late 2007. At that time, the club was losing about £500,000 per month. Those losses have come down through cost-cutting - but that hasn't helped the team.

Keith Houchen's diving header beats Ray Clemence during the 1987 FA Cup final

"Sisu came in with good intentions. But instead of building a squad, outstanding prospects were sold, including Danny Fox and Scott Dann. New contracts for Keiren Westwood, Aron Gunnarsson and Marlon King were never agreed, meaning they all left for nothing."

And, for Turner, the "great killer was last summer - nine players out, three in. You can't survive by doing that. Had King still been here, Coventry would still be a Championship club. He was offered five grand a week more by Birmingham but the owners were not willing to match the terms."

Others reckon the seeds for the Sky Blues' latest relegation were sown years ago, and bear more than a passing resemblance to what happened at Leeds United under Peter Ridsdale., external

Rick Gekoski, who enjoyed unprecedented behind-the-scenes access at Highfield Road during the 1997-98 season when researching his book, Staying Up, argued that former chairman Bryan Richardson had spent heavily in an attempt to keep his side in the top division.

"I have a lot of time for Bryan - I admired his vision and guts in trying to build the club. The fact it didn't work doesn't mean it's wrong. Bryan used to say 'we're having a punt' and they got very close to making it."

Richardson is still clearly hurt by those who suggest the club's current plight is down to him.

"I gave 10 years of my life to run the club full-time and to see what has happened is tragic," he told BBC Sport.

"For nine years I was very popular but for one year it was 'all your fault'. For any club like Coventry it is very difficult to survive year after year.

"Reports that we were £59m in debt when I left in 2002 are rubbish - the actual overdraft was £7m after we sold players following relegation."

The timing of relegation was disastrous, however, with the club already committed to moving from its traditional Highfield Road home to the 32,000-capacity Ricoh Arena.

Richardson had decided four years earlier that Coventry needed a bigger ground to survive.

"It was the only chance we had," he said. "We averaged 19,000 a game and brought in receipts of £5m a year. Arsenal and Manchester United make that in one match now - our break-even attendance at the time would have been 83,000."

But before Coventry finally moved in 2005, and because of the club's parlous financial state having failed to regain a Premier League spot, a deal was struck that meant they became tenants in a stadium jointly owned by a local charity and the city council.

This means the club pay rent - thought to be in the region of £1.2m a year - and do not profit from the sale of food and drink, or the lucrative sell-out pop concerts held there each summer.

When the most recent rent instalment was not paid, there was speculation that Sisu wanted to renegotiate the terms of the deal.

Richardson believes that is exactly what they must do.

"The rent just doesn't stack up. Manchester City did a rental deal with the council based on share of gate receipts. The only way somebody will buy the club is to renegotiate the rent."

As tenants in a barely half-full stadium, and with owners seemingly unwilling or unable to pump sufficient resources into the team, it is going to be hard for the Sky Blues to bounce back next season.