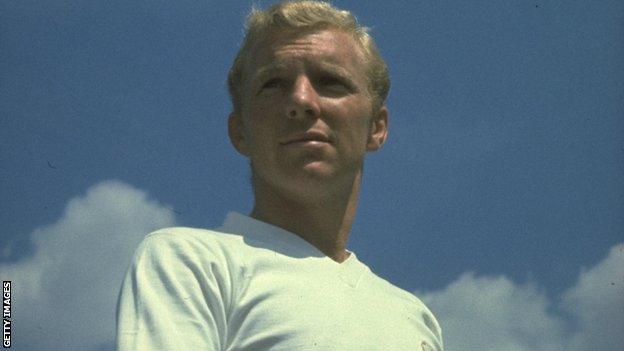

Bobby Moore: Modest, generous, meticulous and very, very funny

- Published

This article and further tributes to Bobby Moore first appeared in The Times newspaper, external and are available online to subscribers. You can also listen again to a special BBC Radio 5 live, external tribute programme

The death of England's greatest captain, 20 years ago today, left a void in the lives of those who knew him that has never been filled. Can it really be two decades since we worked together building Capital Gold from a London radio station into a national sports network?

Others far better qualified than I have judged him as a footballer.

Franz Beckenbauer and Pele have named him the best defender ever.

For me, he was one of the finest men I have ever known. He was meticulous in everything, generous with time and money, modest and very, very funny.

The question is often asked: "Were you in awe of him?" Bobby would never have allowed that to happen. He put everyone at their ease. He treated princes and paupers in the same endearing way. He always made you feel as if you were the most important person in any situation.

For three astonishing years, we travelled around Europe commentating on matches. He always insisted on driving to domestic games because "You do all the real work 'Pearco' and need to be fresh". He would enchant us with football stories of the 1960s, but the tales always threw others into the spotlight. Such a humble man, he never spoke of his own glorious successes.

Sir Alf Ramsey's instructions to Nobby Stiles in the World Cup in 1966 often got an airing. He spoke in hushed tones of the occasion he broke curfew abroad and Sir Alf had his captain's passport placed on his hotel bed for his return. It was a quiet warning of future banishment for miscreants. Bobby heeded it. In his own quiet way, he adored the England manager.

He loved the great Brazil side of 1970, but never mentioned the Bogotá bracelet. He preferred to concentrate on the contemporary game and we'd gossip for hours about players, managers and tactics. In his commentary he urged defenders to stay on their feet and to play out from the back. He told me that a young lad at West Ham United, Rio Ferdinand, would be a star.

Some people denigrate his radio work because he should have been given a loftier role by football's authorities. Of course he should. It's a national disgrace that he was never handed an ambassadorial position. But he was thrilled by his commentary work and the team of young reporters around him. He shared their banter.

Football fans everywhere loved him. Managers and players would turn their heads when he entered a press conference. There would be a nod and a respectful smile. But if they invited him into their office after a game, he would only go if I could accompany him. He didn't want me to be left out.

Hours after their penalty shoot-out defeat by Ireland in the last 16 of the 1990 World Cup, the Romania players entered a small trattoria. They saw Bobby sitting with Mick Lowes, my radio colleague. Led by Gheorghe Hagi, the captain, they instantly walked out. Twenty minutes later Hagi brought them back in, armed with autograph books. Bobby signed them all.

He took me to the eve of the World Cup final banquet. I was hopelessly out of place. But Bob insisted I might get an interview with Pelé. As the crowd parted, the pair embraced as they had done in Guadalajara. Bob waved me over. I rolled the tape machine and started: "Hello, Mr Pelé."

"Hello."

"Have you been in Italy long?"

"Two weeks."

"Has the weather been good?"

"Yes!"

"Thank you, Mr Pelé."

I shuffled away, distraught at my inept interview. Bob put an arm on my shoulder and whispered: "Don't do that to me again, old son." It was a rare cross word, but he could get angry. He fumed if anyone criticised England unfairly. He was England's number one fan. The players knew it.

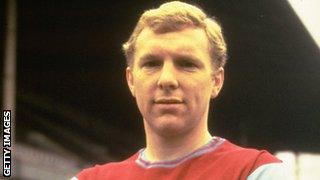

Bobby Moore made 544 league appearances for West Ham

In 1992, leaving Moscow after England's 2-2 draw with the Commonwealth of Independent States (former Soviet republics), Bobby was rudely accosted by armed, burly airport security men because he had unknowingly purchased more jars of caviar than allowed.

One by one the England players came back through the scanner and picked up a jar telling police they had asked Bobby to carry it for them. They all revered the captain of 1966.

Bobby's generosity was boundless. At those wretched 1992 European finals when I had to double up as commentator and hooligan reporter, he saved my skin after two 18-hour days. On the third night of street violence involving England fans, when again I should have been on news duty, I crashed out.

The phone rang in the room with an irate news editor demanding my whereabouts.

"He's asleep," Mooro explained.

"What? There's a riot outside your hotel. Get him there," came the order.

"I'm sorry but there's not. We've moved into the countryside. Listen. I'll put the phone to the window."

But instead of exposing the mouthpiece to the Malmö city centre of smashing bottles and shop windows, our greatest-ever captain slipped it between two feather pillows. Silence.

"So sorry. My mistake. Let him sleep and send a 'voicer' in the morning," said the confused editor. Bobby smiled an enigmatic smile.

Julian Waters, now at Sky TV, was a young reporter with us then. He'd dreamt of seeing a major final. But the station recalled him for financial reasons when England were knocked out. Bobby asked me to his room and gave me enough cash to pay for Julian to stay with the proviso that no one knew. It was a typically kind gesture.

The morning after England were knocked out, we met Alan Ball near the team hotel. He tearfully explained that some of the squad weren't that bothered. Bobby calmed him. They cuddled on an open street in Stockholm. But there was sadness about my hero. He understood by then that he'd never see England lift another trophy. He knew the doctors could not cure the cancer that had started to destroy him. But he never told me.

In the final nine months he was as immaculate as ever. Well groomed and outwardly fit from his daily running routine, he knew time was short. I started to suspect he was poorly. But he kept his own counsel.

In early 1993, I suffered my own cancer scare. Night-time terrors were calmed by calls from Bob. Reassuring as ever, not once did he complain about his own health.

On 13 February, 1993, as I was leaving to cover an FA Cup tie, Nigel Clarke, of the Daily Mirror, tipped me off that the Sunday papers were going to run a story that Bobby was dying. I rang his Putney home. He confirmed it. I was bereft. He was stoic.

He asked me to go to his house to record a global media interview on the Monday. Jeff Powell, of the Daily Mail, a long-term friend, was to write the story for the world. Two days later TV footage cruelly spotlighted his gaunt face in our commentary box at the England v San Marino game. Bobby had been to Wembley one last time.

Two days later Stephanie, his amazing wife, asked me to stop him going to our planned West Ham v Newcastle commentary. We both feared a media circus. So I told this wonderful, brave man that it was unwise to go to his old ground.

"I respect you, JP. I always will. I accept your decision. But you've disappointed me." Bobby never got to Upton Park again. Those were the last words he ever said to me. The following Wednesday morning, he died.

I had flown to Goa the previous night. At the hotel, the manager told me to phone England immediately. As they had no international lines, I had to go by taxi to the nearest village post office. For some reason I must have told the driver I feared that a friend, Bobby Moore, had died.

The post office had three corrugated iron walls and no roof. In the corner was a vintage wind-up field phone. I was put through to London and given the news. I turned around in despair, not knowing what to do next. Outside, the whole street was packed with people listening. In that dusty street on the other side of the world, they knew Bobby Moore. Only then did I fully understand who he was and what he had been.

I will never replace him as a friend. The game will never know his like again. I am truly a lucky man to have shared his time, shared so much laughter and the odd bottle of white wine.

Moore's legendary Jairzinho tackle

- Published25 February 2013