FA Cup final: Wigan's Whelan makes poignant Wembley return

- Published

- comments

You'll be familiar with the theory. The romance of the FA Cup has fizzled out, the magic has long since leaked away. The cup final itself? Bumped into the fag-end of an afternoon, lost amid the clamour and clout of a Premier League weekend.

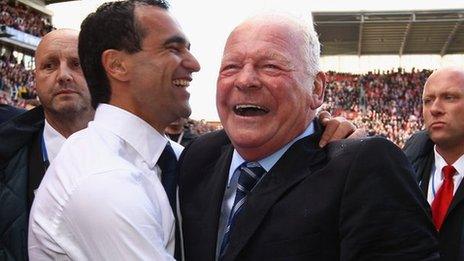

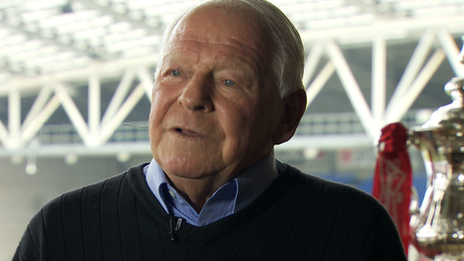

Bah-humbug to theories. Boo-hiss to the naysayers and bean-counters. This Saturday, when Wigan owner Dave Whelan leads his team out at Wembley to face Manchester City, a footballing fairytale that is equal parts darkness and light will come full circle.

It is the story of one career wrecked and another built from the ruins, of painful struggle and mercantile success, of an old man returning to see where his younger self changed forever. And it begins, on that lush Wembley turf, almost exactly 53 years ago.

THE FATEFUL MOMENT

7 May 1960. Whelan, then 23, 77 games into his burgeoning Blackburn career, lined up against Wolves in the FA Cup final knowing the sporting world was watching on.

Whelan is stretchered off after a tackle by Wolves winger Norman Deeley in the 43rd minute

"He was a fearsome full-back, a real tough guy," remembers Bryan Douglas, veteran of 438 league appearances for Blackburn, Whelan's team-mate and life-long friend.

"I wouldn't have liked to play against him; he gave 110% every game. He wasn't particularly good on the ball, but he was very fit and very fast. Opposing wingers never enjoyed playing against him."

Just before half-time, the young left-back - nicknamed 'Crunch' Whelan by Rovers supporters in tribute to his robust tackling - went in for a challenge on Wolves winger Norman Deeley. In that fleeting moment, all would change.

"I knew immediately when he hit me that my leg was broken," says Whelan. "I was running at full pace - obviously you can't stop.

"I saw my leg bend in mid-air. I managed to grab it before I fell to the ground, because otherwise it could have been a compound fracture, the bone straight out of my leg."

THE IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH

"I was near him when he went down," recalls Douglas. "I had a few words with him as he was carried off, and near enough told him we would win the cup for him. It wasn't to be."

Whelan in his hospital bed the day after the final

With no substitutes allowed, Blackburn played on with 10 men. They were beaten 3-0, Deeley scoring twice. Whelan, without a pain-killing injection or gas and air, was in an ambulance racing through the north London streets.

"The first thing I remember after coming round is being wheeled down a hospital corridor with the surgeon at my side," says Whelan. "I opened my eyes and asked him, 'How have Blackburn got on?' He said, 'I'm sorry. You've lost 3-0'.

"I started crying. It just burst out of me. I was absolutely desperate, in despair as I lay in that hospital bed."

Douglas, an England stalwart who played every minute of his country's matches at the 1958 and 1962 World Cups, had to fly straight to Portugal on international duty. In his absence, another family member would step into the breach.

"Our families used to go on holiday together, not just me and him but three or four of the team, all with their wives and children, in those days down to Bournemouth or Newquay," he said.

"My wife had driven down to watch the match. She was expecting, and my second son was born just afterwards. She ended up in hospital in London, about half a mile from where Dave was in hospital, with me away with England. She and Dave comforted each other by ringing each other up."

THE LONG ROAD BACK

Whelan, desperate to return to football, convinced he had been close to joining Douglas in the England squad, put his faith in a radical new treatment.

"It was an experiment, and I was the guinea pig," he explains. "A specialist said he could make players who had broken bones walk.

"They put another plaster on top of the one I had and it went up to my hip. He said the hip would carry the weight, which sounded right. He took me outside on a stretcher and said, 'I want you to get up and walk'.

"I said, 'I can't do that'. He replied, 'I promise you you'll be able to walk. Trust me.' So he gave me these two sticks, and I got up.

"I took three steps and just fell over. They had to take the whole plaster off me and re-do it, because I was getting gangrene in my instep."

Whelan kept that cast on for 10 months. For five months he could only walk with a stick. When the plaster came off, his injured leg was half an inch shorter than the other. After prolonged inactivity, it had also wasted away.

"It was 18 months before I could start to train, and close to two years before I managed to play again. In my mind I knew I'd lost pace and strength, and you can't just build that back.

"When finally I played again, in the old Central League, for Rovers reserves against Sheffield Wednesday at Hillsborough, I cracked it again, in exactly the same place."

NEW BEGINNINGS

Whelan, on just £20 a week, having been paid only £29 for playing in the FA Cup final, knew he desperately needed an alternative source of income. Accustomed to hard physical training, missing the dressing-room banter at Ewood Park, he was also in dire need of stimulation.

"My wife and I had already bought a grocery shop. It used to get busy in the morning and busy in the evening, but was quiet the rest of the time, so in the day I used to go into Blackburn market," says Whelan.

"There was a stall there called the Howard Brothers store, which sold toiletries and medicines. One day I went to buy something there and told Bill, who owned it, 'I'm bored out of my brain-box, I've nothing to do'. He said, 'Why don't you come and work here?'."

Whelan would work on the stall twice a week for the next three months, learning about margins, purchase taxes, "that tuppence in every shilling made 16% in gross margin".

Eileen Hargreaves, now retired, was a member of the Blackburn Market Traders' Association.

"Dave did well, because he was an ex-Rovers player," she says. "People felt they knew him already. And he was very good at pitching his wares - he would be shouting all the time, and the enthusiasm never dropped."

ONE DOOR CLOSES

Even as he used that experience to open his own market stall in his home town of Wigan, Whelan harboured dreams of returning to his first career. Now aged 28, he won a contract with Fourth Division Crewe Alexandra.

"I was never, ever, the same player again," he admits. "I'd lost my pace and without pace in the top division you're dead in the water.

"I had an idea that my football career was coming to an end. I got more interested in business every day and the more I worked on that stall, the more I learned.

"Growing up during the war, when there was no food, and with my dad away in the army for five years, you learn to have your wits about you. Being streetwise helps you in business. I was always good at maths as well. And I loved every single day working on the market.

"You used to get a benefit payment after you'd played football for five years. At Blackburn I'd only been in the first team for three years, even though I'd signed my first professional contract at 17. So they gave me £500, rather than the £750 you could get for the full five years. Less tax, that was £400 I got. I used it to buy stock for my stall."

ANOTHER DOOR OPENS

Douglas and his Rovers team-mates were not surprised to see Whelan wheeling and dealing.

"When you were in the first team, you had a bit of time on your hands, and Dave realised early on what he could do, and how he could put that time to good use," recalled Douglas.

"We always knew that he would be successful in business. He was a hard-working lad through and through. Even as a player he'd come into the dressing room with little offers - 'Have you got any of this, I'll get you some of that…'."

Whelan, fired by a desire to succeed, channelling all his competitive energies into his burgeoning business, would need little encouragement.

"The other players at Blackburn used to get orders off their wives - 'Get this off Dave'. And I used to sell some patent medicines cheap, like Alka Seltzers, which I'd knock sixpence off.

"In the Jewish community in Manchester you could get anything. They had a duty-free supermarket and would do some fantastic deals, all for cash, on the nail."

BUILDING AGAIN

Eager to expand, keen to learn yet more about his new trade, Whelan flew to the US and immersed himself in retailing the American way.

"I knew we were always a year behind them when it came to retailing. When I was there I saw supermarkets selling food and hard goods, all self-service. This had never been heard of in England.

"A shop came empty in Wigan and I thought, 'Mmm, that would make a fabulous supermarket'. So we sold food but also carpets, irons, toasters, all sorts of electrical goods, and it was an absolutely roaring success. They used to queue to get in."

Whelan exported his model across Lancashire. By the late 1960s there were 10 of his 'Whelan's Discount Stores' across the county, attracting the attention of Yorkshire supermarket tycoon Ken Morrison.

Selling out for a then-huge £1.5m, Whelan - the kid left stranded on £20 a week - briefly contemplated a second retirement.

But the bug had bitten. Buying up a local sports shop called JJ Bradburn, he used his American experiences once again.

"Over there, they were laying out all the merchandise in the store - trainers, clothes, the lot," he recalls. "You could pick a tennis racket up and try it, swing it about. In England everything used to be behind the counter in cabinets. So I came back and did it their way."

BACK TO THE START

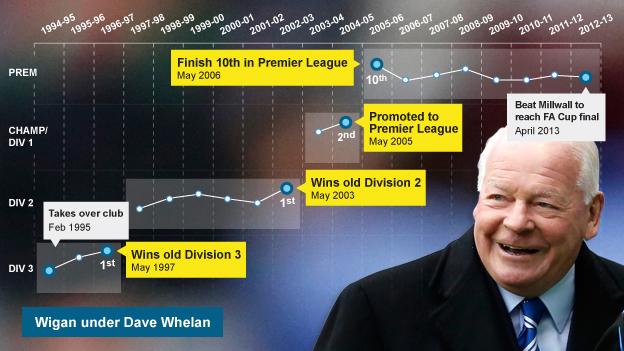

Within six years Whelan had 450 shops nationwide. When, in 1995, Wigan Athletic director Stan Jackson looked around for a wealthy local man to loan the Fourth Division club £760 to cover the players' wages for a week, there was one obvious choice.

Tapped up, Whelan soon dived in. Within a decade the club had made good on what seemed to be a well-intentioned yet empty promise from their new chairman and made it into the Premier League.

Eight years further on, having won through to the FA Cup final, they have returned that largesse with a gift of their own: a return to Wembley, a return to where it all began. For the 76-year-old Whelan, it will be a day of over-powering, and conflicting, sentiments.

"When you play professional football at the highest level, there is nothing like it," he says. "The adrenalin that flows through your body at five to three on a Saturday afternoon is unbelievable.

"There's nothing like it. Not even business or doing a deal can match that. But [Wigan manager] Roberto Martinez has given me the honour of leading the team out, and where I'll come out will be very close to the spot where I broke my leg.

"I'll be really, really proud, I can tell you that. I've always felt I had unfinished business on that pitch. This will finish off one hell of a journey."

Additional reporting by Simon Austin.

- Published7 May 2012

- Published13 November 2012

- Published11 March 2013

- Published9 April 2013

- Published4 May 2013

- Published13 April 2013

- Published12 April 2013