Hull City: Could Assem Allam's Tigers name change benefit club?

- Published

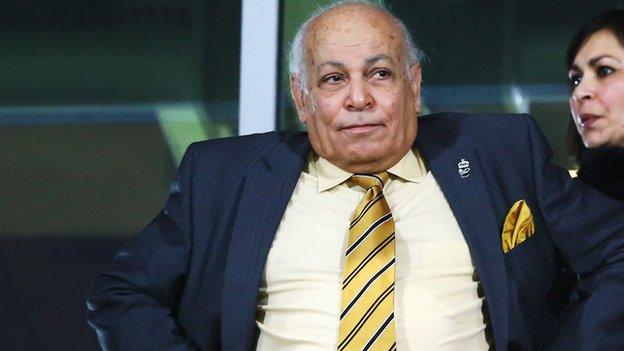

Mindless meddling or a misunderstood masterstroke? Assem Allam's plan to change Hull City's name to Hull Tigers has outraged some supporters.

'City till I die,' roar the vocal protesters as the row over one word overshadows their promising start to life back in the Premier League.

Allam, who became owner of the club in 2010, has stoked the dispute by suggesting he will walk out if the supporters do not back his plan.

But business experts believe there is sense in his desire to make the club potentially more attractive to a wider international audience.

"I think the whole process has been conducted badly with the supporters, but it's a pretty sound idea," says Nigel Currie, director of sports marketing agency Brand Rapport.

"Nearly half of the clubs in the Premier League are called City or United, but you probably think of Manchester City or Manchester United if you're outside England and hear those names.

"It's a global game now, with a pretty saturated market and plenty of competition."

Founded as Hull City Association Football Club in 1904, the club have been known as "the Tigers" for most of their history because of their amber and black kit.

Egypt-born Allam, who moved to Hull in the 1960s, said he had invested more than £70m since taking over the club and helped achieve promotion to the Premier League.

But after failing to secure ownership of the club's KC Stadium from Hull City Council, the 74-year-old claims he cannot afford further funding and additional revenue is needed.

"I think he sees Hull as being not just local to the East Riding of Yorkshire, but potentially a club with national, and international significance," says Simon Chadwick, a university professor in sports business strategy.

"For example, India has one of the biggest populations in the world, with a huge appetite for sport and a growing interest in football.

"A teenager on the streets of Mumbai might not know the difference between, say, Newcastle, Aston Villa and Hull.

"But he knows the word tiger, which has really positive connotations in India - as proud, noble, aggressive and strong."

Aiming to open up lucrative new markets for shirt sales, merchandise and broadcast deals shows commercial vision and could bring benefits, but Chadwick says this needs to be backed up by a proper marketing strategy and investment.

"It's no use thinking changing the name or the colour of the shirt will pay instant dividends," he says.

"Whether you're targeting India, Indonesia or Malaysia, you need a commercial operation set up there."

Some of Chadwick's students at Coventry University are helping the Hull City Official Supporters' Club with a survey of fans to get their views as part of a consultation before the Football Association makes a decision.

The fact HOSC and another supporters' group, City Till I Die, could not agree on a joint statement recently demonstrates a diversity of views.

Currie says it is commonplace elsewhere to have sporting sides with 'brand' names, which can give them a unique selling point.

"You only have to look at American Football, where you have teams like the New York Jets and the San Francisco 49ers," he says.

Owner Sonny Werblin changed the Titans to the Jets in 1963 because he wanted "a star-studded approach", while the 49ers title comes from gold prospectors who rushed to California in 1849.

While the US may be a land of opportunity, there is a word to the wise from one of America's biggest sports.

David Stern, commissioner of the National Basketball Association, warns: "I would say a wise owner would view his ownership as something of a public trust, in addition to the profit motive, and you really do want to allow the fans a little bit more input than I think is being allowed, with respect to Hull.

"I can understand the fans being upset with the change. We take polls, we have mini-elections and we have things like that, because if you lose the support of your home-town fans, you've lost a lot. Certainly seek input from the fans, rather than say 'I don't care what you think.'''

Allam is a successful entrepreneur, with a thriving firm which manufactures and supplies generators, and does not take kindly to his business nous being questioned. He believes the title Hull Tigers is shorter, snappier, more marketable.

"What the fans should be interested in is that I will never change the colour, I will never change the logo. I will never remove Hull," he told BBC Radio 5 live last year.

"The Tigers logo is there and I will never change this without consulting the fans.

"As for the commercial decisions, they are my decisions. The club cannot rely on my money all the time."

Chadwick, who has worked with clubs such as Barcelona and Tottenham Hotspur, states it is hard to put a price on the commercial difference a rebrand can have.

He notes that controversial Cardiff City owner Vincent Tan's decision to change the club's shirts from beloved blue to radical red has yet to cause a big stir in the Far East, where red has the reputation as a lucky colour.

"I do a lot of work in China and South Korea, and I'm not hearing anything about Cardiff," he said.

"I understand what Vincent Tan is trying to do, but I don't have the sense the numbers are there, and he needs to be transparent about that."

Rebranding exercises can come unstuck if opponents organise themselves.

"The Gap clothing company tried to change the design of its logo in 2010 without fully consulting its customers, who organised a social media campaign against it, and the company backed down," said Chadwick, a born-and-bred Middlesbrough fan.

While club merchandise sales could theoretically rise abroad under the revamped Hull Tigers banner, there could be damaging implications at home, where 25,000 fans gather for big games.

Fans have threatened to boycott matches, cancel season tickets, stop buying club products and to hold protests at the ground.

In an area famed for its rugby league roots, with Hull Kingston Rovers and Hull FC (briefly renamed Hull Sharks in the 1990s), it is worth noting that sport had a major makeover.

"It wasn't easy because in England we are largely traditionalists and don't like change," says Maurice Lindsay, who helped drive the formation of the Super League.

"When we wanted to change the names of clubs like Wigan, Leeds and Warrington there was a lot of huffing and puffing, but I think it went successfully," he said.

"Life moves on and if you look at sport around the world - from rugby league in Australia to English cricket - clubs are branded. It adds a little bit of modern youthful zing."

Allam does not see much zing about the word "City". He has called it "lousy", which is ironic given Hull recently celebrated being named UK City of Culture for 2017.

- Published15 January 2014

- Published12 December 2013

- Published2 December 2013

- Published7 June 2019