Qatar 2022: Influential Gulf state is desperate to retain World Cup

- Published

Driving in Qatar is not for the faint of heart.

At rush hour in Doha, the capital of the Gulf state, getting around town is usually a white-knuckle ride.

Buses, super-sized 4x4s, concrete mixers, trucks, motorbikes and some of the world's fastest supercars, driven by mega-rich locals, all converge on the highways that snake around the city.

World Cup 2022: Qatar determined to retain tournament

With no evidence of a common set of driving rules - or a willingness to use indicators, for that matter - the end result is often chaos, congestion and crashes.

Qatar's government believes the situation is set to improve as huge infrastructure projects near conclusion, including a £9.5bn ($16bn) underground metro system.

As one dusty billboard near the newly opened airport puts it: "Qatar deserves the best!"

That state-sponsored message sums up Qatar's level of ambition and is reflected in Doha's skyline, a dizzying array of steel and glass structures that gleam in the blistering desert sun.

It's on the 34th floor of one of those skyscrapers, the Al Bidda Tower, that the organising committee for the Qatar 2022 World Cup is based.

Despite recent allegations of corruption levelled at their bid, staff here are determined to press ahead with delivering football's premier international tournament.

That's because, for Qatar's elite at least, the World Cup is a catalyst for yet more change in the Gulf state. But it's also much more than that.

Back in the mid-1990s, Qatar successfully accessed vast reserves of natural gas and oil.

While there may be decades of fossil fuels still to be extracted beneath the desert sands, there is a recognition within the state of the need to build, diversify and prepare for a time when those natural resources become depleted.

Given the constantly shifting political plates within the Middle East, Qatar also recognised some years ago that it needed to think long and hard about its standing on the world stage.

Sport is at the very heart of its core strategy and winning the right to stage the World Cup in 2022, external is its most notable milestone to date.

Other steps have been taken, too.

The state's sovereign wealth fund, which invests in foreign companies, already owns French Ligue 1 champions Paris St Germain, while the name of Qatar's state-owned airline adorns Barcelona's famous shirt., external

World number one tennis player Rafael Nadal is a regular competitor in Doha

The world's top tennis players, golfers, cyclists and athletes are regular visitors to Doha, while Qatari-owned thoroughbreds continue to make their mark on the turf at Europe's finest racecourses.

This building of sporting bridges with the world's biggest names, brands and competitions is an example of what diplomats refer to as 'soft power' - the projection of shared cultural values designed to help protect a country's interests and build alliances with key international powers.

So the threat to strip Qatar of the 2022 World Cup following allegations of corruption and vote-buying - allegations "vehemently" denied by the tournament's organisers - strikes at more than just the prestige that hosting football's premier international event would bring.

The 2022 World Cup is the catalyst to Qatar's political, social and sporting future - and the Gulf state is determined to hang on to it.

Last week, Hassan Al Thawadi, the secretary general of the Qatar 2022 supreme committee, travelled to Oman to meet Michael Garcia, the independent ethics investigator appointed by Fifa to root out any wrongdoing in the bid process for both the 2018 and 2022 World Cups.

Qatari sources say the meeting was "comfortable" for Al Thawadi and other officials present.

But several voices within Fifa, including Uefa president Michel Platini, the only man to admit casting a vote for Qatar, have said there should be a re-run of the bidding process for 2022 if corruption is proven.

Hassan Al Thawadi has met Fifa investigator Michael Garcia to discuss claims of wrongdoing

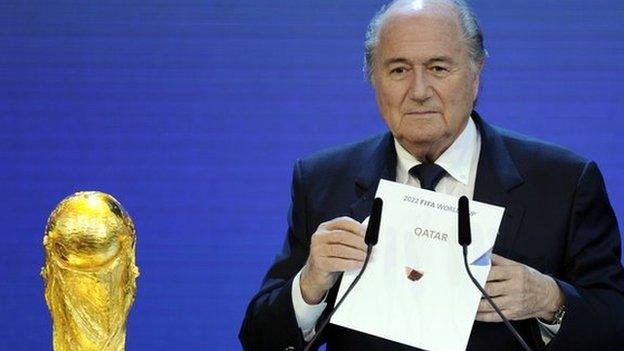

Qatar's bid committee has spent more than £298m ($500m) in the four years since Fifa president Sepp Blatter took to the stage in a Zurich conference hall and announced the Gulf state had prevailed over Australia, Japan, South Korea and the United States.

Until now, there has been a reluctance to discuss specific numbers.

But with half a billion dollars now deployed, as Qatar starts to deliver on its bid promises, the overriding message such a revelation sends is that the gloves are coming off in the battle to keep its hosting rights.

The potential financial ramifications for Fifa if it was to revoke Qatar's victory could be significant.

Qatari officials privately say they want to avoid a legal showdown - potentially at the Court of Arbitration for Sport - with Fifa.

But given the threat they face - and their denial of any wrongdoing - all options are thought to be under consideration.

Within the Al Bidda Tower, Qatar 2022's staff are acutely aware of what is at stake. At the reception desk, a monitor displays a countdown clock indicating the months, days, hours, minutes and seconds until the tournament is due to begin.

Due to current consultations over whether the tournament should take place in summer or winter, given Qatar's extreme temperatures in June and July, it's fair to say the clock is far from definitive.

Nevertheless, in Al Wakra, a district to the south of Doha, the first stadium for 2022 is now under construction.

A computer-generated image of the stadium in Al Wakra, which is now under construction

Designed by Zaha Hadid, the architect behind the London 2012 Olympic aquatic centre, it is the first of five stadiums that will be under construction by the end of this year.

"We need to deliver on our promises, but this is a case of not just us delivering on what we promised, the whole country is mandated to deliver this World Cup," said Thani Al Zarraa, a senior engineer and project manager for Qatar 2022.

Significantly, other voices are starting to emerge within Qatar to defend its right to stage the World Cup.

Nasser Ali Al Mawlawi is not a man used to answering questions from the media but is likely to one of many key figures stepping forward to defend his country's interests.

As the chief executive of Ashghal, Qatar's public works authority, he is responsible for a £16bn ($27bn) investment in his nation's expressways.

High up in his penthouse office, over small glasses of tea, he spoke about the impact on Qatar should it lose the 2022 World Cup.

"It will be very sad for us as a people," he said. "Back in 2010, we were really happy to host. At the same time, I'm really confident that we have won it in the right way. This isn't just a World Cup for Qatar, this is a World Cup for the entire Middle East."

If Qatar is to host the first Middle Eastern World Cup, then the next few weeks will be crucial to its hopes.

It is not just facing corruption allegations, it is also fighting claims that moving the tournament from its traditional summer slot will be too disruptive, plus ongoing issues over the rights of workers.

Qatar insists it will not build stadiums "on the blood of innocents" and is taking action to improve the terms and conditions of workers.

But organisations such as the International Trade Union Confederation claim that recent reforms by the Qatar government are "cosmetic" and simply don't go far enough.

The ITUC believes "modern slavery" exists in Qatar and wholesale reform of labour laws is needed to stop workers dying and to improve conditions.

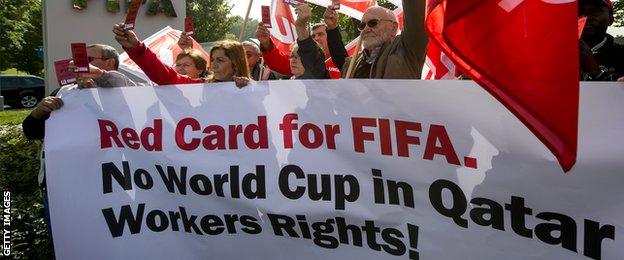

Fifa has been subjected to protesters claiming that migrant workers are being treated badly in Qatar

As for the dates for the tournament, a recommendation is likely to come in early 2015, with the expectation that November and December of 2022 will be put forward by the taskforce led by Fifa executive committee member Sheikh Salman.

But will Qatar's bid make it to that stage?

Garcia concluded his ethics investigation on 9 June, against a backdrop of weekly allegations from Fifa files leaked to the Sunday Times.

His report and recommendations are expected to be delivered to Hans-Joachim Eckhart, Fifa's independent ethics adjudicator, in mid-July.

Garcia's planned update at Fifa's congress this week may not reveal much either.

In any case, Fifa's ethics chamber only has the power to caution and sanction individuals, not entire nations or bidding committees.

It will therefore be up to the governing body's powerful executive committee to decide, if corruption is proven and directly linked to Qatar 2022, what action should be taken.

Once again, politics will play its part, especially with the Fifa presidential election due to be contested next year.

Ultimately, given the bid processes for both 2018 and 2022 were ran in tandem, with allegations of collusion between voting nations already in existence, it may be difficult to re-run just one in isolation.

In that same vein, it is difficult to believe there is much of an appetite within Fifa to upset Russia, which is due to stage the 2018 tournament.

That's all before the fury of the Arab world is factored into the equation if Qatar were to be stripped of its winning bid status.

Strong representations from the heads of confederations supportive of Qatar are believed to be behind last October's statement from Blatter that Qatar 2022 would definitely go ahead.

Fifa president Sepp Blatter is likely to have the final say on Qatar 2022

However, when asked last week to give his opinion on Qatar's prospects in light of the fresh allegations, he replied that he was "not a prophet".

Nevertheless, Blatter is likely to have the final say on the tournament's viability - if Garcia's report provides him with the political capital to act.

- Published9 June 2014

- Published9 June 2014

- Published7 June 2014

- Published5 June 2014

- Published6 December 2013