David Smith's beautiful life - cheating tumours and death

- Published

You're flat on your back in a hospital bed and the pain is indescribable. There's a hole in your spine where they drilled through your neck and hacked out a tumour the size of a tennis ball. You can't walk. You can't sit up. You can't eat. Be honest - what might you be thinking?

I wish I'd done this? I wish I could have done that? Why me? Cocooned in a world of self-pity, regret and resignation, maybe you just want death to swoop down and carry you off to a more peaceful existence.

Not David Smith. Never heard of him? Keep reading. Then tell your friends, your partners, your parents, your kids. In fact, tell anyone who wants to listen. Because Smith's cocoon was a fantastical world of the wildest possibilities. And his story might even change the way you live.

"A lot of people might have given up," says the 37-year-old Scotsman, who almost died twice in May 2010, first when surgeons removed the tumour and again when they removed a blood clot that replaced it, which was crushing his spinal cord like a twig.

"But when I came round from the anaesthetic, my first thought was: 'The London Games are only two years away - I need to get back in a boat.'

"Having that goal, it gave me such an overwhelming drive. At no point during my recovery did I think: 'I'm so happy to be alive.' All I thought was: 'I've got to get my place back and be on the start line in London.'"

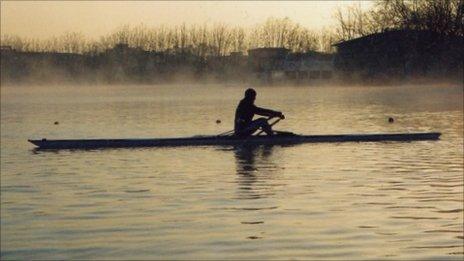

Smith recovered from surgery to win gold at the London Paralympics, as part of the mixed coxed four

Seventeen months later, Smith was on the start line in London. Three vertebrae light, his neck a bionic structure of cages and screws, Smith won a gold medal as part of the mixed coxed four at Eton Dorney. How's that tickly cough? How are those sniffles? Thinking about staying in bed?

Smith believes he might have become inured to adversity long before he can remember. Having been born with two club feet, he almost lost both legs in early childhood. His legs were saved, but the wearing of special plaster cast boots left his right foot deformed and fused.

Nae bother. Smith, who grew up in the mountain town of Aviemore, played shinty and took up karate, making the British team at the age of 15. He also competed in skiing and athletics at a regional level, and all this against the so-called able-bodied.

In bobsleigh, as a brakeman, Smith missed out on a place at the 2006 Winter Olympics by a couple of hundredths of a second. It was a moment that simultaneously broke his heart, galvanised his mind and altered his perception of what constituted success and failure.

"I get my inspiration from anyone who lives with passion, in any walk of life," says Smith. "But I'm most fascinated by the people who give it everything and don't quite make it."

Having been told by his physio that his body was breaking up and was no longer suited to careering down an icy track at 80mph, Smith roamed the hills around his home and pondered his possible future - the horror of a 'real' job. In an office, behind a desk. Another definition of death.

Smith posted this photo last October, two days after surgery to remove a tumour for a second time

Then he learned that his foot deformity qualified him for Paralympic sport. Five months after climbing into a boat for the first time, Smith won a gold medal at the 2009 World Rowing Championships in Slovenia. Then came the tumour.

"When I found out there was a lot of relief," says Smith. "I'd been ill for so long, waking up every day in pain. The series of tests leading up to the diagnosis was horrendous, very invasive, but they all came back clear.

"So to sit in that room and see the doctor holding up that MRI image, showing me the tumour, it was a case of 'wow, thank you, at least I know what's going on now'." Now Smith could see his foe, he knew where to direct his punches. And Smith punches harder than most.

Despite cheating death twice and triumphing at the 2012 Paralympics - "I don't think I could ever put into words how special that moment was" - Smith still sought fulfilment. So after London, he switched to cycling.

"Cycling was that thing I'd been searching for my whole life," say Smith. "They call the time trial the race of truth, because there is no hiding. It's just you and the bike. And when I'm on my bike, I don't think about my health. It's the only time I'm not in too much pain."

Smith won a spot in the British development team and his progress was rapid. He made the podium in a number of able-bodied time trials. A spot at the 2016 Paralympics was suddenly a tangible possibility. "Everything was laid out perfectly," says Smith. "But I started not to feel too great...

"... it was August 2014 when the tumour came back. I walked into the room and my surgeon, Tom, gave me this look. My stomach just sank and I thought: 'Hold it together and ask all the questions you have to ask. Don't cry, don't cry, don't cry…

Last month, seven months after spinal surgery, Smith climbed Mont Ventoux - three times in one day

"... I went outside, looked up at the television screen and they were showing the cycling stage of the Commonwealth Games triathlon. I felt tears running down my face..."

His surgeon didn't spare him. Smith was told that he had a one in 500 chance of survival. That he might be paralysed from the neck down. That he might lose both lungs and spend the rest of his life on a ventilator. That he might lose function in both hands. That his cycling career was over. That last revelation stung the most.

So here you are again. Flat on your back in a hospital bed and the pain is indescribable. There's a hole in your spine where they drilled through your neck and hacked out a tumour the size of a tennis ball...

... you can't walk. You can't sit up. You can't eat. You're covered in a rash and your skin is hanging off you because you've lost so much weight. You're drugged to the eyeballs, unable to move pretty much anything below the waist. Be honest - what might you be thinking this time?

Smith's first thought after coming round from the anaesthetic? "Rio 2016 is only two years away - I need to get back on a bike."

Adds Smith: "After the first two surgeries, I thought: 'I could never do that again.' But I had no choice, I just had to get on with it. I could have let it defeat me but I never thought it would. It was almost like a battle."

Unable to exercise his body from his hospital bed, Smith put muscles on his mind. He meditated, visualising himself on a bike, using videos downloaded onto his laptop for inspiration. Once home, he stuck a picture of Rio on his wall, ate like a champion and got pedalling in his garage - before spreading his broken wings and riding an eddy of sweeter pain.

"Every day I reminded myself that the pain when I'm on a bike was so much nicer than the pain I had when I was lying in hospital," says Smith. "The pain you feel on a bike makes you feel alive, hospital pain is a totally different game."

Last month, Smith cycled up Mont Ventoux, one of the most brutal mountains tackled in the Tour de France. Three times in one day. Last Friday, he competed for Great Britain in the first Para-cycling World Cup event of the season in Maniago, Italy. After finishing 16th, he declared himself "fairly happy".

He wants to be on the start line at the World Championships at the end of July. Smith is living furiously, because the spectre of death could darken his door at any moment.

"The tumour I have is linked to a cell with a 68% recurrence rate," says Smith. "So I wake up every morning, focus on that day and try not to think too much about the future. That's a scary prospect, because the future might not just mean no sport, it might mean me not even living to see another Olympic Games.

"I could sit around and wait for the tumour to come back or I can go out and do what I'm passionate about. And that's pushing myself to the limit.

"There are days when I'm on my bike and I think how lucky I am to be able to ride when I could be in a wheelchair, paralysed from the neck down. Even when it's snowing and I'm suffering like hell, I think how lucky I am.

"I'm grateful to have gone through everything I've gone through - the illness, the surgery - because those low points have given me an appreciation of the real beauty of life."

Smith says he struggles with his status as an 'inspiration'. Despite it all, he says, he's still the same person he was - before the multiple medals and incisions. But it means a lot to him when people tell him they've heard his story and tailored their lives accordingly.

That they're no longer sitting around and waiting for life - good or bad - to come to them. That they're out, doing what they're passionate about, pushing themselves to the limit. Appreciating the real beauty of life.

- Published25 July 2019

- Published31 August 2016

- Published28 November 2013

- Published2 September 2012

- Attribution

- Published5 August 2011