How a double amputee is racing a superbike at 150mph

- Published

- comments

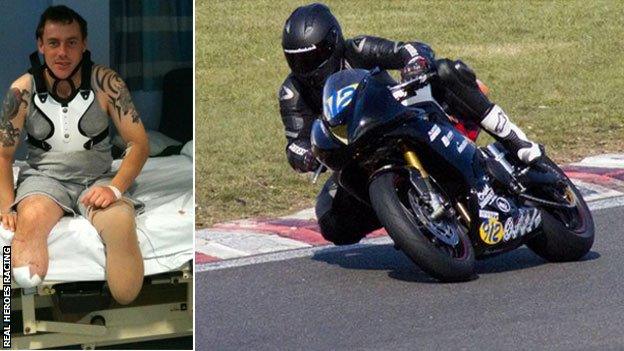

Murray Hambro is no ordinary motorcycle racer.

For a start, the 33-year-old is racing in a national championship after just a handful of races.

Secondly, he and his team are all novices.

Finally, he is a double amputee, with no legs from just below the knee.

In December 2010, Hambro was serving as a Lance Corporal in the Second Royal Tank Regiment in Afghanistan, external when his tank drove over a 65kg roadside bomb.

Hambro, who was at the top of the tank in the turret, was sent flying by the force of the explosion. So was a passenger in the tank.

"The explosion blew all the doors off and the passenger was projected out of the vehicle," explains Hambro.

"He lost one of his legs and his spleen. I was sent 40 feet up in the air, came down and landed on my side. My injuries included breaking all the bones in my feet, breaking my pelvis, ripping my liver and spleen, six fractured vertebrae at the top of my neck, and the all-important one, I cut my nose.

"It was a pretty big one."

The driver was also injured, suffering a broken arm and a broken ankle. "He got lucky," says Hambro.

First on the scene was a colleague from the vehicle directly behind.

"He leapt out and did the whole Baywatch, external thing," Hambro recalls. "Running in slow motion through the dust and dirt.

"He gave me first aid and just sorted me out. He told me not to look at my legs and made sure I got out of there alive."

Hambro gave his son Harley, who was born in March 2013, the middle name Nicholas, after the friend who risked his life to give him that first aid.

After being evacuated under fire to Camp Bastion in Helmand Province, external and then being transported on to the new Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, Hambro remembers the feeling of relief when he was told by a consultant he had fractured both feet in the explosion.

Murray Hambro - Double amputee is superbike racer

"I was happy with that," he says. "I thought: 'Well, a bit of plaster for maybe six to eight weeks and I'll be up and about again.'

"But then he said: 'The right one is a no-brainer, it's got to come off. We could try to rebuild the left but you will be in and out of hospital for the next two to three years and the end result could be you lose it anyway.'

"So I thought: 'While they're at it they may as well have both feet.' Within 48 hours of getting to hospital, I was a double amputee."

The naturally optimistic Hambro admits having "a few bad days" coming to terms with losing his legs. After 11 years in the army, he was facing an uncertain future but was determined to walk again by August 2011, in time for his wedding.

In fact, he managed to take his first steps by the end of February, just three months after his double amputation.

Murray Hambro aboard his Triumph race bike

He was back out on the roads on a newly-modified motorbike by April of that year, against the advice of his surgeons.

"After my operation, the surgeon asked me what my hobbies were," he remembers. "I told him: 'I ride motorbikes.' He looked at me and told me to get a new hobby."

But Hambro, who had started riding motorbikes at the age of seven in fields near his home, was not to be deterred. After a particularly bad day of pain and discomfort, he treated himself to a new Triumph motorbike.

He did not know if he would even be able to ride without legs but set about finding out.

The rear brake, which is normally operated by the right foot of a motorcyclist, is now housed on the right handlebar and is controlled by Hambro's thumb.

The gear lever, usually operated by a rider's left foot, has been replaced by up and down shift buttons on the left handlebar. A similar system is used on Hambro's race bike.

Moving about on the bike was the biggest problem, as he found his feet were slipping off the footpegs. So he drilled a hole in his boot to allow him to 'attach' it to the bike. That helped a lot.

Being back on the road was an important step in proving that his disability would not prevent him leading the life he wanted to.

X-ray of Hambro's feet after he was thrown from his tank by a 65kg bomb. Both had to be amputated

"I was nervous the first time I went out on the road," Hambro says. "I didn't know what to make of it.

"But my family were just as keen for me to get out on the bike as I was. My wife and I used to go out together a lot before, with her on the back, so to be able to do that again was great. She loves it. It gave us some normality back."

After getting married, Murray was introduced to Phil Spencer, who asked if he would be interested in joining his race team, True Heroes Racing., external Hambro had never ridden competitively before.

The team is run in association with the Afghan Heroes charity, external, which was set up by Denise Harris, the mother of a soldier killed in Afghanistan, and aims to help wounded service personnel who have returned to the UK.

Despite admitting that they had no real idea what they were doing, Spencer and Hambro managed nine weekends of club racing last year before securing a place in this season's Triumph Triple Challenge,, external a support class in the British Superbike championship.

"My first race was very daunting," Hambro admits. "I still had my road riding head on, guys were coming up to lap me and I was just pulling over and letting them through.

"I didn't know what to expect to be honest. I then got chatting to the other racers and they told me I had to be more aggressive and hold my lines. So I adopted that philosophy and stuck to it.

"Overtaking my first rider felt like a race win."

This season has not been straightforward for True Heroes Racing. They have suffered technical problems, struggled to set up a new bike after it arrived late, while Hambro slid into a tyre wall at Thruxton, external after an 80 mile-per-hour crash.

He has approached all these obstacles with the same black humour. After all, this is a man who has "LEGLESS" embroidered on the back of his race leathers and a tattoo of himself being blown up on his back. He also has a personalised number plate that spells out "No Feet" on his car.

When he says he doesn't do "self-pity", he certainly means it.

True Heroes Racing are already looking to expand next season and hope to be able to help other injured serviceman who are coming through rehab get a new lease of life.

"My job used to involve people throwing grenades at me. so I guess it makes racing less scary," Hambro says.

"I still get nervous on the track but you'd be crazy if you weren't. I know that nothing serious will happen to me. The worst-case scenario is a broken bone or two."

He says his naturally positive mindset and "sick" sense of humour have been key in adapting to his new life.

"In Afghanistan, everyone is out to kill you so it's a different ball game altogether," he says. "There are low points, days when it is painful and you struggle to get up and think: 'Why isn't this working?' But I don't have too many.

"If I feel like I'm having a bad day, then I do something to cheer myself up. The team name is True Heroes, but I don't consider myself a hero at all. If anything, I was stupid enough to get blown up."