Amy Williams: Olympic champion swaps skeleton for rally co-driving

- Published

One minute Amy Williams is telling me she's becoming more sensible the older she gets, the next she's telling me of her plans to sail round the world in a rib boat., external

Which is "a bit like a dinghy". Although she's not quite sure.

"I get sea sick and I don't particularly like water," says former skeleton star Williams, who became the first Briton to win individual gold at a Winter Olympics for 30 years in Vancouver in 2010., external "But when someone asks me to do something and it interests me, why on earth would I say no?"

'Just Say Yes' could be Williams's motto. Perhaps better to be almost involved in a 100mph pile-up with a colossal stag in the wilds of Scotland than sitting on your settee, piling food into your face and watching Strictly.

To clarify, the collision with the stag took place on land, not at sea. And Williams was the passenger in a car, not a rib boat. Which is a bit like a dinghy. We think.

Archive : Amy Williams wins Olympic Gold in Vancouver

Williams, you see, has swapped chucking herself downhill on what looks like a tea tray for the life of a rally co-driver. The rib boat can wait. Out of the frying pan, into the fire and the oil and the exhaust fumes.

"I did a TV show in September and one of the features was rally driving," says Williams, 31, who hung up her sled last year after a struggle with injury.

"Tony Jardine,, external the motorsport broadcaster and rally driver, happened to be watching and he suggested I get an international co-driving licence for the Wales Rally GB in November., external Since then we've been going up and down the country - Scotland, Wales, wherever - doing national-level races."

Williams, who was tutored by top British co-driver Daniel Barritt, completed the four rallies required but had one or two hairy moments. "At the Cambrian Rally," she says, "I got a little bit behind with my notes and Tony was probably going too fast and couldn't hear me.

"We took a tight corner through this forest track and it was only his quick-thinking and experience, and the fact we'd just upgraded to a more powerful car, that stopped us going over the edge and falling 15 feet.

Williams reached speeds of more than 90mph on the way to winning gold at the 2010 Winter Olympics

"As for the stag, I didn't notice, because I was reading my notes. All I heard was this noise next to me: 'Oh…' Apparently it missed our car by inches. If it had hit us, it would have been fatal. Obviously for the deer. And maybe us."

The principle job of a rally co-driver - relaying so-called pace notes to the driver, in order that they don't fall 15 feet over edges - sounds a bit like trying to solve complicated puzzles while being kicked down a staircase in a supermarket trolley.

"It's been intense, the steepest learning curve of my life," says Williams, who will be competing in the final round of the World Rally Championship, external in Cardiff from 14-17 November. "I've done what most people do in a few years in a few months.

"In Wales we'll have two days of recceing and three days of rallying, with night stages. I'm also the time-keeper - if you check in too early or too late you get penalised. And I'm almost a team manager, organising everyone. The driver has the easy job in the sense he just sits in and does what I tell him to do."

All in all, Williams has a stack of responsibilities, so you wonder why Jardine hasn't plumped for somebody with a bit more experience. The answer, in short, is because Jardine has seen her chucking herself downhill on what looks like a tea tray - and that takes almighty bravery, and no little skill.

"Tony saw that the qualities I'd developed from doing skeleton could transfer to rallying," says Williams, a former national-level 400m runner. "The way I can process things at speed, the speed itself... these are things most people would be quite scared about.

"I know what it's like to be on the edge, pushing yourself to the limit, attempting to go as quick as you can without crashing. So I didn't hesitate when Tony asked: 'Do you want to do this?' I just said: 'Of course I do.'"

While Williams claims she is happy to be "a normal, sit-on-the-sofa, watching TV kind of girl", she also admits the adrenalin rush created by travelling on a sled at 92mph, with the tip of her nose a couple of inches from the ice, has been impossible to replicate.

"When you're living your life at 80, 90mph, that becomes the norm," says Williams, who will be an ambassador for Team GB at next year's Winter Olympics in Sochi,, external as well as a pundit for the BBC.

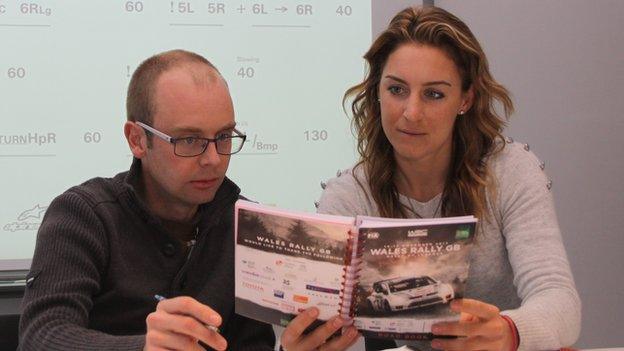

Williams, who became a co-driver in September, learns the ropes from top British exponent Daniel Barritt

"It doesn't feel fast any more. You're always looking for that flutter in your belly. And a fairground ride isn't really going to do that for you.

"So it was a case of, 'OK, what's next?' And the first time I got out of a rally car I was shaking with adrenalin. In fact, the only thing that has ever come close to skeleton is sitting in a car with a driver going extremely fast."

On one level Williams's "need for speed" is a selfish ambition - "I'd love to learn to rally drive. Hello? Who wants to challenge me to drive a rally car?" On another level it is a mission statement, a way of altering perceptions of what is and isn't possible, especially among women.

"Whatever you're doing, there are elements of risk," says Williams, who also spent a week in the African wilderness with former England cricketer Andrew Flintoff, among other post-Olympic challenges.

"Things are fatal, people can die. But if there's an opportunity to do something that takes you out of your comfort zone, then do it. You can constantly surprise yourself with what you can physically and mentally achieve.

"I'd love to go off and do more challenges. Maybe not quite on the James Cracknell level, but there aren't many women doing these things. I'd like to show women: 'Hey, we can do more than maybe we think we can - maybe we're a lot tougher than we think.'"

Chucking yourself downhill on what looks like a tea tray will do it. As will solving complicated puzzles while being kicked down a staircase in a supermarket trolley. Next up the rib boat. If only she knew what one was.

- Published2 May 2012

- Published9 November 2017