Wimbledon 2013: What's happened to the teenagers?

- Published

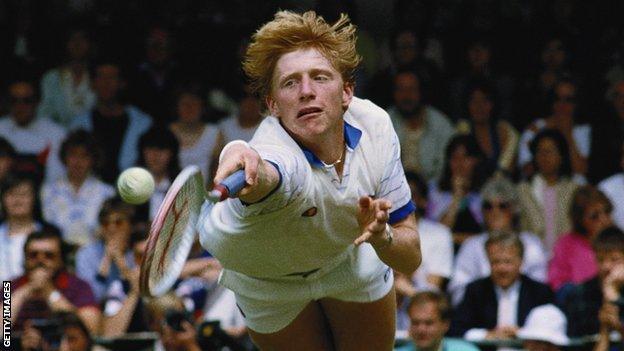

When Boris Becker won the men's singles title at Wimbledon in 1985, external it wasn't his age in itself that was remarkable. It was the manner in which the 17-year-old cut a swath to glory that left many open-mouthed.

Big-serving, imposing at the net, brimming with muscular vigour. Here was a boy who made men look like boys.

In truth, some of the top players of the time didn't need a strapping German teenager to make them look little. John McEnroe was built like a bus ticket; two-time champion Jimmy Connors wasn't much bigger. Becker wasn't an aberration, rather the dawning of a new age of bully and brawn.

Fast forward 28 years and just about everybody on the men's tour is built like Becker. Only bigger. Show me a 17-year-old who is built like Novak Djokovic and I will ask to see his birth certificate. Which goes some way to explaining why the teenage tyro in men's tennis is consigned to the history books.

As it stands there isn't a single teenager in the ATP Tour's top 100, while 20-year-old Bernard Tomic, world ranked 61, is the youngest player left in the Wimbledon draw.

"I was able to come in at 15 and play on the tour week in, week out," says Australia's Lleyton Hewitt, the 2002 Wimbledon champion, external who at 20 was the youngest male ever to be ranked world number one.

"But it's harder to do in this day and age, with how big and strong the guys are and how physically demanding it is. The guys serve and hit the ball so big and it's very hard as a teenager to match it."

Of course, Becker wasn't the only kid to win a big one during that era. Mats Wilander (1982) and Michael Chang (1989) won the French Open aged 17; Stefan Edberg (Australian Open, 1985) and Pete Sampras (US Open, 1990) won Grand Slam tournaments aged 19.

Interestingly, Becker refuses to countenance the idea that the dearth of teenage talent at the top of the men's game has anything to do with increased physicality. Instead, Becker reckons we're simply experiencing a lull as a result of poor coaching. But it's quite some lull.

Of the 940 players who have spent time in the top 100 in the history of the ATP rankings, 16% broke through as teenagers. Between 2001 and 2011, that figure dropped to 12%. But at least some were breaking through.

In the 2000s, Hewitt, Andy Roddick, Rafael Nadal, Djokovic and Andy Murray broke into the top 10 before they were 20. Others, such as Roger Federer, Richard Gasquet and Juan Martin del Potro, managed to break into the top 20.

Wilander won the French Open aged 17

"Everybody is getting a lot smarter in terms of how they need to train, how to recover," says Germany's Tommy Haas, 35.

"Everybody has a physio and gets the right treatment, everybody has the right diet, all those things you can do to get your body in the right shape. And everybody has a good work ethic.

"We're more professional today, we take better care of ourselves," says seven-time Wimbledon champion Federer,, external "in terms of the way we eat and the way we live our lives, the way we approach matches in terms of warming up and so forth.

"It means we have less teenagers in the game and that's a worry."

But it isn't only the improved conditioning of established players that is preventing teenagers from breaking through, it is the heightened physicality of the game in its modern form.

Given slower courts across the board, heavier balls and improved racquet and string technology, men's tennis in 2013 is not for the fragile.

With less-experienced players unable to hit through top-ranked stars as they might have been able to do on faster surfaces in years gone by, instead they find themselves being ground down, week after week, from behind the baseline.

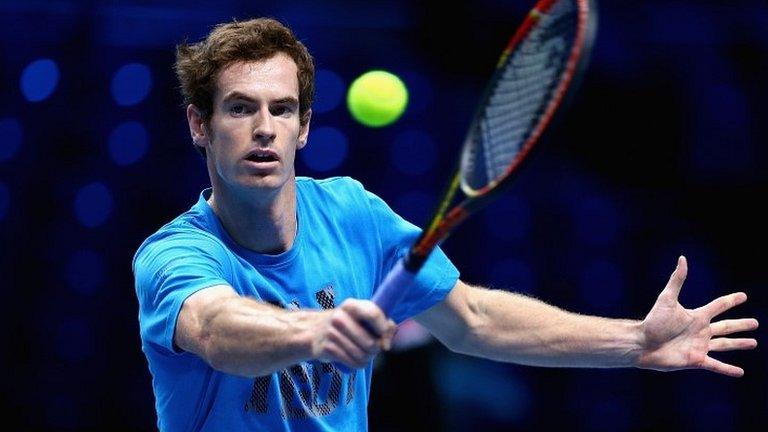

Remember Murray in his younger, less robust days, repeatedly hitting the deck because of cramp., external And remember Del Potro, who won the US Open in 2009, external at the age of 20 but who missed nine months of the 2010 season with a wrist injury.

But there are other factors in play. While prize money in the main ATP World Tour, and in the Grand Slams in particular, has mushroomed, in the second and third division Challenger and Future events it has stagnated.

"There's massive money in the four big tournaments," says British number seven Jamie Baker. "But if you show up to a Futures tournament and you lose in the first round, you're walking away with about $150."

"Prize money should increase at lower level," says American James Blake, 33. "It's tough when there's three of you crammed into a hotel room and you're eating pizza just to get by because you can't afford anything else."

In effect, tennis has evolved on the same lines as Formula 1. Once, an ambitious team wanting to break into motor sport's blue riband competition, external could do just that, given a fair few quid in the bank, a couple of engineers and a spare gear box in the garage.

But F1 in its ultra-professional modern form prevents anyone except for mega-rich, multi-national constructors from breaking in.

Back when Becker was winning Wimbledon for the first time, a top player might have had a coach, although some didn't even have one of those. Today, Murray and any top player worth his salt will be surrounded by a five or six-person team, widening the gap between established stars in the shop window and wide-eyed kids staring in.

And so there are no teenagers like Becker in the modern game - boys making men like look boys. Men's tennis is exactly that in 2013.

- Published26 June 2013

- Published25 June 2013

- Published25 June 2013

- Published9 November 2016

- Published30 May 2013

- Published30 May 2013

- Published17 June 2013

- Published8 November 2016