How should the media tackle sport's mental demons?

- Published

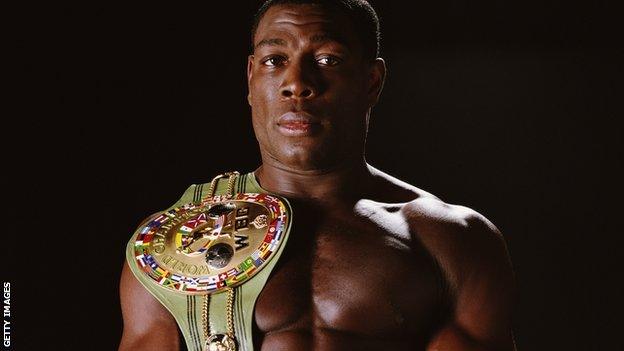

The Sun's original headline, above the 2003 story of former heavyweight champion Frank Bruno's admission to a psychiatric hospital,, external did not last long.

"Bonkers Bruno Locked Up", was changed to "Sad Bruno in Mental Home" by the time later editions rolled off the presses.

The revised words were still criticised by mental health charities.

Eleven years on, after high-profile cases including Stan Collymore, Marcus Trescothick,, external Neil Lennon, external and Robert Enke, has the reporting of mental health issues in sport improved?

A panel including cricketer Michael Yardy, whose depression became public knowledge after he left England's 2011 World Cup campaign,, external and the Professional Footballers' Association head of welfare Michael Bennett met at MediaCity UK in Salford to discuss how they would change reporting of mental health in sport.

Don't mistake performance for insight

It may be tempting to look for indications of a sportsperson's mental health while they are under the spotlight in competition.

But it is often when people are free to reflect, rather than when they are consumed by the action, that problems can arise.

Yardy's last one-day international was England's six-run win over South Africa in Chennai on 6 March 2011

"After I left the World Cup, Geoffrey Boycott took my depression to be a reflection of my performances,", external explained Yardy.

"But it is not always about performance.

"There are times that I have performed brilliantly, driven home, gone to bed and not been right in myself.

"I think I had my worst bouts of depression during the winter months when I have been away from cricket.

"Sometimes it is actually nice to have the ball and bat in your hand and it is just you in that moment.

"Conversely fielding can actually be quite difficult because if you have bowled a bad last over or something you can 'catastrophe' things."

"There is an assumption in the media sometimes that something on the field of play has triggered these issues and it is not always the case," added Daily Telegraph columnist Jim White.

Be sensitive to the sufferer as well as the subject

A survey by mental health charity Mind earlier this year showed that 60% of people were encouraged to seek help for their own mental illness after learning about a sportsperson with similar problems.

Coverage of a sportsperson's problems will have an effect on those consuming it just as it does on the star at the centre.

"The way that these are issues are dealt with around big heroes in the sports pages is read, watched and listened to be people who suffer from depression themselves," said White.

"If the analysis is that a sportsperson should have nothing to worry about, then you start to question the validity of your own problems.

"The way we deal with it is not just to be sensitive to the suffer themselves, but the way it is presented to everyone else."

A common problem, in many different guises.

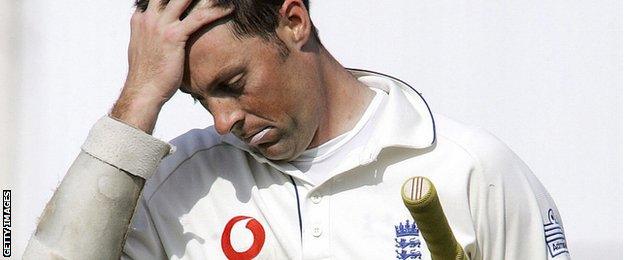

When England batsman Jonathan Trott left the Ashes tour of Australia in November with what the ECB described as, a "long-standing stress-related condition", the end of Marcus Trescothick's international career came to mind.

Wracked with depression, Trescothick dissolved into tears at Heathrow's duty-free in 2006, as he prepared to board a flight to Australia with his team-mates., external

Trescothick has continued his successful county career with Somerset since retreating from the international scene

But Trott later revealed that he was "emotionally and mentally spent" rather than depressed when he flew home. Former England captain Michael Vaughan said that he felt conned by the impression that Trescothick and Trott's cases were similar.

"A lot of players come to talk to me about things and I'm happy to speak to them but I have my own issues and everyone is very different," said Yardy.

"It is very dangerous to say that one case of depression is the same as another."

"It is now very clear that Jonathan Trott was not in the same boat as Marcus Trescothick," Sky News Sports editor Nick Powell added.

More positive stories

Stories about mental health issues tend to focus on the trauma suffered, rather than the triumph over the odds.

"We never talk about positive mental health, it is always seen negatively," said Bennett.

"We need to change that around so it is seen as a positive that someone is confident enough to come forward and share their issues."

"People who have suffered with mental health are actually very strong in that they have kept it inside so long and continued on in spite of it," added Yardy.

Only mates do banter

It is the white noise to which the serious business of the dressing room is played out to - joking and joshing, mockery and mirth. But does banter have to stop when it comes to mental illness?

"In a strange way I embrace it, because the worse thing can be that people feel they can't have a joke with you," said Yardy.

"People do take the mickey out of me, but in a closed environment and they know the boundaries. You obviously have to know somebody very well."

- Published25 November 2013