Leicester City win Premier League: The greatest sporting story?

- Published

- comments

John Daly winning the US PGA Championship in 1991 and Buster Douglas beating Mike Tyson in 1990 are two other amazing sporting shocks

Leicester City's 2016 Premier League triumph is an astounding sporting story.

Relegation favourites, led by a new yet simultaneously tarnished manager, driven on by a former non-league striker, prevailing over teams with incomparable resources and title-winning pedigree.

But is it the most remarkable of all time? More romantic, more impossible, more captivating than any that other years, sports and nations have thrown up?

The maverick who became magic

John Daly went from ninth reserve for the tournament to US PGA champion in 1991

You want romance? You want the impossible? John Daly wasn't just an unfancied outsider for the 1991 US PGA title,, external a rookie who had missed the cut in almost half his tournaments. He wasn't even due to take part.

When you are ninth reserve for a major full of millionaires, you generally plan something else for your week. As the players above him started dropping out, Daly - blond mullet, bad shirts, worse trousers - instead stuck his clubs in the boot of his car and drove the eight hours from his home to Indianapolis.

He had never seen the Crooked Stick course before, let alone played it, but when Nick Price's wife went into labour the night before the first round, the Zimbabwean was out and the chubby no-hoper in.

No time for a practice round, only to ask Price's caddy, Jeff 'Squeaky' Medlin if he might help him out that first morning. "John was like a blind man with a guide dog," said his playing partner, Billy Andrade. "'Where do I hit it here, Squeaky?'"

The answer was further than anyone else. Daly's prodigious driving was matched only by his relentless cigarette smoking. After rounds of 69, 67 and 69, he high-fived his way through the final round to win one of the biggest prizes in golf by three shots.

"All four days, I didn't think," he said afterwards. "I just hit it."

It became a motif for Daly's life - his victory celebrated at a McDonald's drive-through, sticking his head through the sun-roof of a hastily-hired limousine to make the order; spontaneously donating $30,000 to the family of a spectator killed by lightning earlier in the tournament (which later put the man's orphaned daughters through college); careering through four marriages (thus far) and an estimated $60m in gambling; reduced now to parking his giant RV outside the Augusta branch of Hooters during Masters week and flogging John Daly T-shirts to anyone staggering out.

He no longer plays professional golf. But he still smokes, relentlessly.

In 1991 John Daly won the US PGA Championship - 19 years later, after losing an estimated $60m gambling, he was selling signed merchandise from his motor home outside the Masters

The underdog who bit back

Douglas was a 42-1 underdog, coping with flu and the recent death of his mother, when he beat Mike Tyson in Tokyo

Daly's achievement was the more remarkable for the fact that he went through four rounds of 18 holes, against the best golfers in the world, and came out on top.

In the same way, Leicester's league title, the inevitable result of unarguable superiority over a 38-game season, must surely outrank the great one-off upsets that sport habitually throws up.

Buster Douglas should never have beaten Mike Tyson when they met for the undisputed heavyweight world title in Tokyo 26 years go. Tyson walked into the ring with 37 wins from 37 pro fights, 33 of them coming from knockouts. Douglas was a 42-1 stooge, an astonishing price in a two-man contest. He was physically sick, struggling with flu, and emotionally stricken by the death of his mother three weeks before the fight.

Six unlikely top-flight titles

Tyson even had Douglas on the canvas in the eighth round. Yet in the 10th he was down himself, the victim as much of hype and hubris as his opponent's brutal uppercut. Unlike Douglas, he would not beat the count.

It was arguably as big an upset as Cassius Clay beating Sonny Liston in Miami 26 years further back, before Cassius became Muhammad Ali and Ali changed the world.

But it was a one-off, at least for Douglas, the boxing equivalent of a sensational FA Cup coup. Douglas could not sustain his underdog day. Leicester have made their own revolution a routine.

The callow kid who became a champion

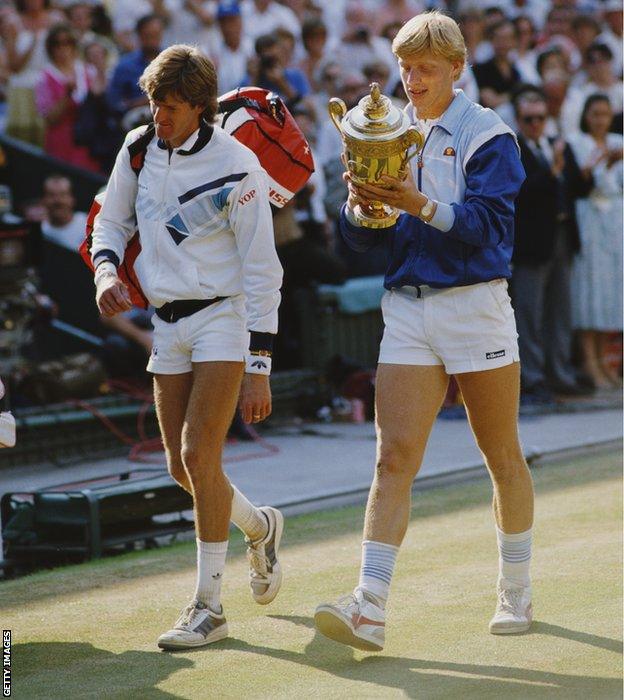

Unseeded 17-year-old Boris Becker was supposed to be studying for college exams in 1985 - instead he came through seven matches at Wimbledon and left with the men's singles trophy

As golf has four rounds to pare away the lucky and the one-punch wonders, so tennis Grand Slam tournaments have seven rounds across two weeks to truly test their champions.

All of which made Boris Becker's win at Wimbledon, external in 1985 so astonishing: 17 years old, unseeded for the event, supposed to be studying for exams at college, instead becoming the youngest champion in history, a red-topped tornado of car-crusher serves, diving volleys and sawing fist-pumps.

And yet. A week before he had won the grass-court event at Queen's, confirming the special marriage between his serve-volley game and that fastest of surfaces; heading south across London, he was ranked 20th in the world, an outsider but one homing in fast.

Neither was it an entirely unfamiliar take. Three years before, another 17-year-old, Sweden's Mats Wilander, had gone to his first French Open and beaten the second, third, fourth and fifth seeds en route to triumphing in the final.

Five years later a third 17-year-old, Michael Chang, would also win the French Open, another kid-become-man in a fortnight that few saw coming.

Chang's famous fourth-round victory over three-time French Open champion Ivan Lendl is worthy of a biopic on its own - two sets and a break of serve down to the world number one, so stricken with cramp that he was reduced to hitting moon balls and underarm serves. But just like Mark Edmondson, shock winner of the 1976 Australian Open having begun it ranked 212th in the world, he would never win another Slam singles title.

Leicester have beaten last season's champions, and the champions of the season before that. They won more matches across the nine months of the Premier League season than any other team. Week after week, they have maintained their trajectory.

The team that united a nation

The Boston Red Sox went 86 years between World Series triumphs

As Leicester's title bid gathered momentum, it became increasingly clear that they were taking other supporters with them - first the romantics, then the neutrals, then all but the hopeful fans of second-placed Spurs and a few diehards at East Midlands rivals Derby and Nottingham Forest.

By the end it was the story almost all of football seemed to want to happen. Which was pretty much the way it was with baseball's Boston Red Sox, going into the World Series of 2004., external

The Red Sox had won five of the first 15 World Series. Then, having let Babe Ruth go to the New York Yankees, they would go 86 years without another, the Curse of the Bambino adding a melodramatic moniker to a litany of bad management, catastrophic errors and heart-breaking near-misses.

In both 1946 and 1967 they lost the World Series in the final game of seven, doing the same again in 1975 in arguably the greatest Word Series ever.

In 2004 they were 3-0 down to their arch-rivals the Yankees in the American League championship series and seemingly doomed again. Then they won the next four games straight, and there were suddenly no neutrals left. Into the World Series, up against St Louis Cardinals, the team that had denied them in '46 and '67. Another four straight wins later, the longest wait was at an end.

And that was what it was: a wait for something that should have happened before, as much about failing to win when history, support and influence suggested they should as finally doing so again.

Leicester? Leicester had never won the league title before. The closest they had come was a solitary second place, 87 years before. Never since had they come close, let alone four times gone into the final games of the season as one of only two teams who could win it.

Back from the dead to rise again

There is the romantic, and then there is the 1981 Grand National.

Bob Champion, a jockey who had come through testicular cancer and a brutal course of chemotherapy; Aldaniti, a steeplechaser who had broken down so often that vets were convinced he would have to be put down.

At Aintree that April it was not so much redemption as resurrection. Champion took Aldaniti into the lead off the 11th fence, and over the remaining 19 the two great survivors could not be touched.

Even in second place came a tale to touch the heart: Spartan Missile, a horse bred, owned, trained and ridden by a 54-year-old dreamer named John Thorne; Thorne only on board because his son Nigel, who had been earmarked for the ride, had been killed in a car crash; Thorne the man who Champion celebrated his win with in a Wiltshire pub later into that Saturday night; Thorne who himself was to lose his life in a fall at a point-to-point race the following year.

A fairy-tale, then, but also one that enough punters saw coming to make Aldaniti 10-1 second favourite as the starter called them in. Spartan Missile was 8-1.

Leicester began their own canter in August so far out in the market that you could get 10 times the value on Andy Murray calling his first-born child Novak. Or Simon Cowell becoming the next Prime Minister.

The journeyman who beat the world

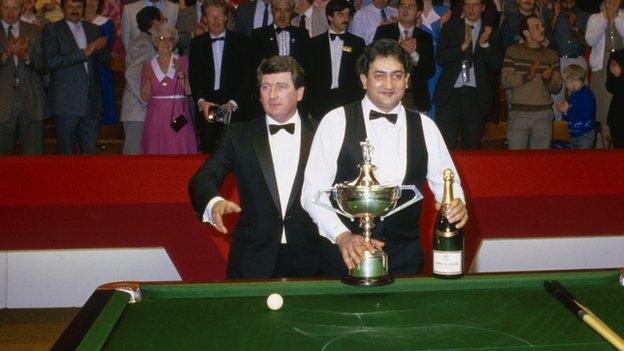

Joe Johnson became, in 1986, the longest-priced winner of the World Snooker Championship

Leicester's well-travelled central defensive pairing of Robert Huth and Wes Morgan are 31 and 32 years old. Younger, then, than the 33-year-old former gas board employee Joe Johnson when he travelled from Bradford to Sheffield for the 1986 World Snooker Championships,, external having lost on both his previous visits, on one of those occasions by 10 frames to one.

The father of six had won his first televised match only the previous year. Despite that undistinguished track record and the pain from a cyst on his back that first brought a halt to his quarter-final and then actually burst in his semi-final, he fought through to meet world number one Steve Davis, held a 13-12 lead going into the fourth session, and then won five of the next six to become, at 150-1, the biggest outsider to ever win the world title.

Classic Arrows - Eric Bristow v Keith Deller 1983

Neither could it be considered a golden blip, in the way Keith Deller's shock victory over Eric Bristow at the 1983 World Darts Championship came to be seen. Johnson reached the final again the following year, even if he has no record of his greatest match; having recorded it all on video, he later discovered that his son had taped over it with He-Man: Masters of the Universe.

Claudio Ranieri is unlikely to suffer the same problem. Neither do the achievements of his team suffer by comparison. Odds of 150-1 make you a long shot. At 5,000-1 you are not considered a shot at all.

The men who made miracles

In three seasons Nottingham Forest won promotion to the First Division, became champions of England and conquered Europe

And so we come to the most apposite comparison of all.

Nottingham Forest, 13th in the old Second Division when Brian Clough took over as manager in January 1975. Promoted to the First Division in his second full season, champions of England in the next, champions of Europe a year later.

Four years and five months from nowhere to the European Cup. Retaining the European Cup, external the following year. It is unlikely ever to happen again.

Caveats? The mean of spirit might point to the fact that Forest played nine matches to win their first European Cup, compared with the 13 present holders Barcelona had to get through en route to the Champions League last season, or that they won six to Barca's 11.

But that has less to do with somehow cheapening their achievement and more about the changing format of the competition. Forest beat reigning European champions Liverpool en route that year, just as they had finished seven points clear of them in winning the league title in 1977-78.

You might argue too that Clough came into that spell with a superior record to Ranieri, having taken similarly unheralded Derby to the League Championship and semi-finals of the European Cup. Maybe, with Leicester just one season into Ranieri's reign, it would be more accurate to limit the judgement to Clough's first landmark at the City Ground: winning the title having only finished third in the Second Division the season before.

Instead of contrasts, however, this is all about the similarities - two maverick and charismatic managers; two sets of muscular centre-backs; two sets of low-key toilers touching the stars. For Forest's dancing winger John Robertson see Leicester's Riyad Mahrez; for former Fleetwood Town striker Vardy, see Garry Birtles - signed from Long Eaton for £2,000, former builder, his goals in Forest's unlikely ascent carrying him to a similarly unlikely England debut.

Better to relish both than to relegate one. Sport, often predictable if seldom straightforward, should celebrate them equally.

- Published2 May 2016

- Published3 May 2016

- Published3 May 2016

- Published2 May 2016

- Published20 June 2016

- Published7 June 2019

- Published2 November 2018