Nick Kyrgios: Is Australian world number 14 wasting his talent?

- Published

- comments

Nick Kyrgios is hugely talented but his commitment and determination has been questioned

It was a very Nick Kyrgios thing for Nick Kyrgios to do.

At the Shanghai Masters on Wednesday he did not just lose to a man ranked almost 100 places below him, having won his preceding tournament in magnificent style, but seemed to scuttle himself mid-battle: patting the ball over the net rather than serving, walking back to his chair before a serve from his opponent had landed, arguing with the umpire, arguing with spectators, swearing to all quarters.

A very Kyrgios thing, followed by a very Kyrgios reaction: internet outrage, opprobrium from former players, condemnation from those in Australia convinced he is both betraying his own talent and the accepted sporting ethos of their nation.

Ex-players react because they recognise in the 21-year-old Australian the sort of tennis gifts bestowed upon very few.

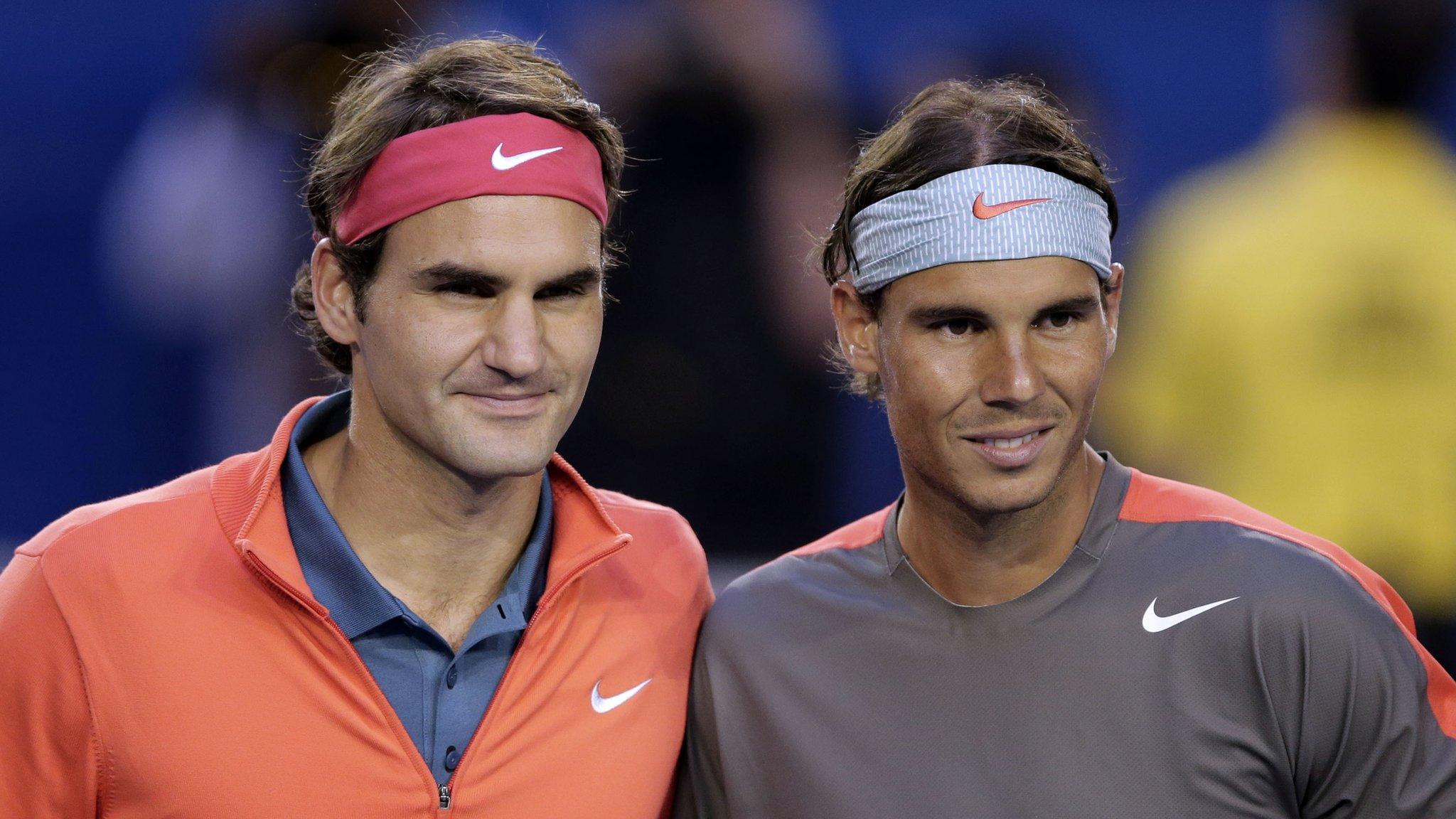

Spectators care because when he is good, he is outrageous: beating Rafa Nadal as a 19-year-old ranked 144th in the world, hitting winners between his own legs; serving with a rhythm and pace that can blow rivals away; hitting forehands with a racquet speed that means the court is his... when he chooses.

On Wednesday, he did not. "Can you call time," he asked umpire Ali Nili at one point in his 6-3 6-1 loss to German Mischa Zverev, "so I can finish this match and go home?"

If what goes on in the 21-year-old's head doesn't always seem to make sense, neither does the response to his actions.

This is Kyrgios's ability, and Kyrgios's career, to do with as he decides. We might wish we had his talents, and many might think they would use them differently. But if he blows his natural lottery, no-one will suffer as much as the man himself.

Making the wrong kind of headlines |

|---|

Kyrgios rants at umpire during 2016 Australian Open match - January 2016 |

"Why shouldn't I take cocaine?" world heavyweight boxing champion Tyson Fury recently asked a reporter from Rolling Stone. "It's my life, isn't it? I can do what I want."

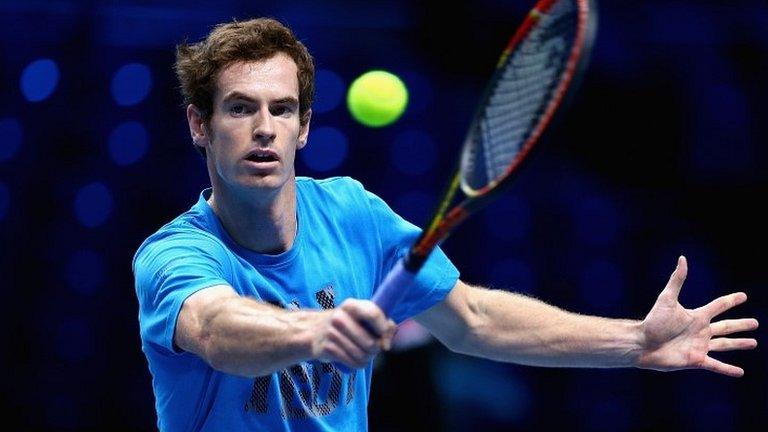

Kyrgios attempts to win almost all the tennis matches he plays. When he appears to tank - as against Britain's Andy Murray at Wimbledon this summer, and in losing to Frenchman Richard Gasquet the year before - it assumes an almost moral dimension.

Only deliberate cheating ranks ahead of not trying on the list of sporting crimes.

Kyrgios is not the first tennis player to be accused of not trying, and he is not the highest profile of sportsmen to admit to it. Five-time world snooker champion Ronnie O'Sullivan has twice deliberately spurned the chance of making a 147 break as a protest at the tournament's prize money for a maximum.

Yet for an Aussie, raised in a culture of never giving in and never, ever whingeing, it is a sporting sin that many find unforgivable.

Sally Robbins, the Australian rower who dropped her oar in exhaustion and lay back on a team-mate in the final of the Olympic eights in Athens in 2004, was castigated across the nation, the mood summed up by the Melbourne Herald Sun's famous line, "It's eight, mate, pull your weight.", external

So it has been for Kyrgios, the first home-grown male to reach the quarter-finals of the Australian Open in a decade, under a burden of expectation ever since winning the junior version of the tournament in 2013.

"Well done Andy Murray. Give this guy a hiding. He is a disgrace," tweeted Australian rugby union legend Michael Lynagh as his performance in a Wimbledon fourth-round match prompted John McEnroe to remark in commentary that "it doesn't look like Kyrgios wants to be out there".

World heavyweight boxing champion Tyson Fury is another sportsman who has defended his right to make his own decisions, regardless of whether or not it damages his sporting prospects

"You're testing our patience mate - show us what you're made of and how hungry you are to be the best in the world," wrote cricketer Shane Warne in an open message on Facebook. "It's time to step up and start winning, no excuses. No shame in losing, but show us you will never give up, that you will give it everything to be the best you can be."

Maybe that anger is justified. Spectators pay to watch sport because they expect a genuine contest. Maybe too there can be sympathy for a young man who appears adrift in a world that he is not suited to.

"I don't have a doubt that if I wanted to win Grand Slams, I would commit," Kyrgios told the New York Times in August. "I'd train two times a day, I'd go to the gym every day, I'd stretch, I'd do rehab, I'd eat right. But I don't know what I want at the moment."

Kyrgios is also doing rather well for a supposed bottler. He has just won the Japan Open, is up to 14 in the world and has so far won, in his short professional career, more than $3.5m (£2.9m) in prize money. He is certainly doing better than Bernard Tomic, the last great Aussie hope, who at two years older has attracted equal controversy without the same success on court.

"Nick, you can't play like that," umpire Nili told him in Shanghai. "It's just not professional. This is a professional tournament."

It is a valid criticism only if you are convinced you want to be a professional player. Kyrgios, obsessed only with basketball as a kid growing up in sleepy Canberra, has never pretended to share the dedication of those above him in the rankings.

"I don't love this sport," he said after that Wimbledon defeat by Murray. "There are so many more things to this world than tennis for me. Not tennis at 30 years old. Please. Not even for fun."

Immaturity? Entitlement? It is worth reminding yourself of this quote - "I hate tennis with a dark and secret passion" - and the identity of its author, eight-time Grand Slam champion Andre Agassi.

Michael Johnson - hugely talented but unable to handle the pressure and gone from the game at 24

Professional sport may appear a dream to those who watch it, but for those who live it, the experience can be a cruel shock: joyless, unrelenting, a betrayal of why they fell in love in the first place.

"I used to love boxing when I was a kid," Fury has said. "It was my life. Then you finally get to where you need to be, and it becomes a big mess."

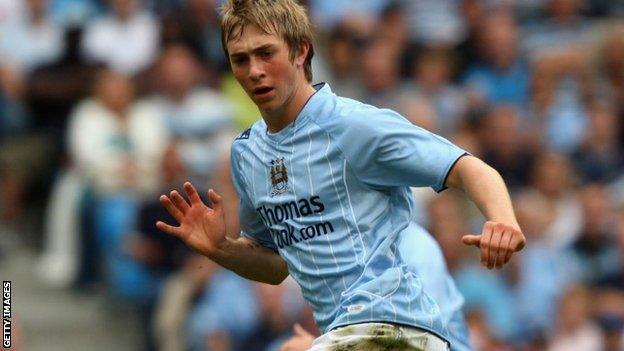

For every O'Sullivan, who has managed to keep playing and keep winning at an age when previous greats were long spent, there are other great sporting talents who lacked the mental skills to back up the physical: former Manchester City midfielder Michael Johnson, unable to handle the pressure of expectation and injury; former Manchester United and West Ham midfielder Ravel Morrison, unable to match his off-field behaviour to his immense footballing gifts.

"Pressure affects everybody, but people deal with it in different ways," says Johnson, dubbed the new Steven Gerrard at 19, retired from football at 24. "We all have different skill sets, whether it is football or any job, and I don't think I had the best skill sets to deal with it."

Kyrgios is not the first tennis talent to threaten not to win the big titles others believe he should. Both Gasquet and Frenchman Gael Monfils, ahead of him in the world rankings, can play breathtaking tennis for half a match and then crumple in the remainder.

What those two have managed, however, is to lose with charm. Kyrgios too frequently appears less iconoclastic than petulant.

"If you don't like it, I didn't ask you to come watch," he said after his defeat by Zverev in Shanghai.

"Just leave. If you're so good at giving advice and so good at tennis, why aren't you as good as me? Why aren't you on the Tour?"

Former world number four and Agassi's one-time coach Brad Gilbert wrote a book entitled 'Winning Ugly'.

Kyrgios, sometimes a winner, just as often seen as a loser, is currently vacillating vacuously.

- Published12 October 2016

- Published9 October 2016

- Published10 October 2016

- Published13 October 2015

- Published17 June 2019

- Published9 November 2016