Russia doping ban lifted: What now for sport after Wada decision?

- Published

Briton Sir Craig Reedie is Wada's president

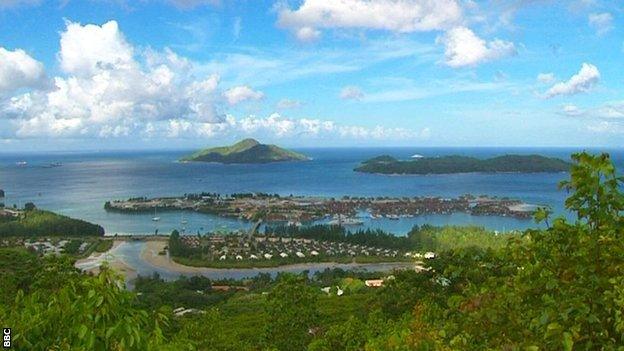

Of all the places, it had to be the dream holiday location of the Seychelles...

For the World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada), it was the lavish setting for possibly the biggest decision it had ever faced.

In a move reminiscent of Sepp Blatter's glory days at Fifa's helm (think back to the infamous choice of Mauritius for its 2013 annual congress), the executive committee of the notoriously under-funded Wada jetted in to one of the world's most glamorous destinations and defied unprecedented anger from athletes and national anti-doping organisations by paving the way for Russia's re-admission to world sport after the biggest doping scandal in history.

For Sir Craig Reedie, Wada's beleaguered president, this has been anything but a tranquil few days in a luxury hideout. Just off the crystal-clear waters of bewitching Eden Island - where he and his committee members gathered this week - a storm has been brewing.

The decision was never really in doubt - not from the moment Wada's compliance review committee recommended such a step last week, despite admitting that the assurances of the Russian sports minister "falls short of what is required".

But it is still one that some fear could threaten the credibility of an organisation charged with safeguarding the integrity of sport. So what does it mean, and what will happen now?

This is far from the first time that the great Russian doping scandal has reached boiling point since it first erupted in 2015. And in the past, some of sport's biggest events have been affected.

Chaos and confusion reigned in the build-up to Rio 2016 for instance, until the International Olympic Committee (IOC) controversially defied Wada's demand for Russia to be banned on the eve of the Games.

Earlier this year, the Russian team was suspended from the Winter Olympics, but then 170 of their athletes were allowed to compete as 'Olympic Athletes from Russia'. At this summer's World Cup, Russia's suitability to play host came under scrutiny.

This time there is no major sport event on the horizon. But it might just be the gravest crisis Wada has faced in its 19-year history because this has become an issue that more than any other has exposed the inherent conflicts of interest that lie at the heart of the organisation, and the difficulties its governance structure creates.

And unlike in 2016, when Wada incited fury among the sports federations by baring its teeth and standing up to the IOC (albeit in vain), this time it has dismayed athletes by being perceived to have rolled over.

Reinstating Russia's anti-doping agency (Rusada) after three years in exile removes one of the few remaining barriers to lifting the bans still imposed on Russian teams by both athletics' governing body, the IAAF, and the International Paralympic Committee (IPC).

Wada's executive committee met in the Seychelles - the luxury Indian Ocean destination - to make its decision on Russia

Only 19 Russian athletes were allowed to compete at last year's World Athletics Championships in London, and just 30 at the Pyeongchang Paralympics in February.

Although the IAAF continues to take a hardline stance, insisting that Russia must still meet its own criteria for reinstatement, the country can now be much more confident that it will be able to send a full-strength team to Doha in the world championships next year, and compete under its own flag.

It will once again be free to start bidding for major events, (there is already talk of a bid for the 2023 European Championships), test its own athletes & issue TUEs.

But it is also symbolically significant because for many it will mark the moment Russia is officially welcomed back into the fold after its years in the international sporting wilderness.

And after I revealed the extent to which Wada's leadership was eventually prepared to secretly compromise with the Russians - not once but twice - in order to help pave the way for their return, the sense from many is that Russia was let off the hook, an impression that inevitably does lasting damage to Wada's claim to be the guardian of clean sport.

None of this should really come as a surprise. Wada is co-funded by the IOC (which represents the commercial interests of the sports movement, and which wants a compliant global anti-doping agency) and governments (who naturally want to know their investment is helping to catch the cheats).

And with six members of Wada's all-important executive committee representing each side, the organisation has always struggled to reach the consensus and secure the strength and independence it needs to be a true global watchdog that exists to protect clean athletes, regardless of any damage its decisions may mean for the image and reputation of sport.

But rarely before has Wada's handling of this saga caused such consternation or division, with an unprecedented mobilisation of athletes and national anti-doping agencies in the West.

The danger is that in the wake of this decision some governments lose faith and pull their Wada funding, and that some national anti-doping agencies take a step back and consider their relationship with Wada.

There is a danger the IOC - which has remained curiously quiet during this recent crisis - then follows suit, with some sports federations perhaps seizing the chance to direct investment towards the International Testing Agency, established by the IOC last year and seen to be more closely aligned with the interests of the Olympic movement.

Rusada director general Yuri Ganus (left) with Wada president Sir Craig Reedie

Reedie - an IOC member who, for many, personifies the conflicts Wada struggles with - can refer to the progress Rusada has undoubtedly demonstrated over the past year or two, and make the point that cheating in sport is far from just a Russian problem, with the West certainly far from perfect when it comes to anti-doping.

One can only imagine the pressure Wada's president has come under - given Russia's importance as a host of international sports events - to find a way of breaking the impasse.

He can point to the fact that the outrage at this decision will be restricted largely to western countries, and the criticism he has been subjected to in the past within the Olympic movement by some for standing up to the IOC, and the need for diplomacy and pragmatism in his position. And he will argue that it is preferable to have Russia back within the anti-doping system, with more chance to monitor its standards, than it remaining in exile.

As unpalatable as it may be for some athletes - especially those, like Britain's Kelly Sotherton, who had to wait 10 years before receiving her medal last week from the Beijing Olympics, having originally been denied by a Russian cheat - Rusada had to return to compliance one day.

And at least Wada can point to the "strict conditions" Russia must now adhere to, with a pledge that the suspension could be re-applied if access to samples at Moscow's anti-doping lab was not forthcoming.

Jonathan Taylor, chairman of the CRC, said: "What we have now is a written commitment from the minister of sport to provide access to the analytical instruments, to an independent expert... and it can be determined whether or not there is a case to answer. And if samples need to be reanalysed as part of that process, then there is also a commitment to provide them."

But while many will naturally be sceptical that Russia will willingly hand over any data that could lead to further prosecutions of doping cases, another problem is that having been seen to quietly move the goalposts for reinstatement, Wada will no longer be trusted to enforce such a threat.

Will other countries who breach Wada's rules in future now know that as long as they sit it out and wait a deal will eventually be struck?

With Wada's original demand for full access to the samples and data in the Moscow anti-doping lab now somewhat watered down, will the suspicion that already surrounds Russian athletes linger and intensify?

And what will those athletes who have found their voice, but who feel ignored by the organisation they hoped was there to protect their interests, do now? Will more follow the lead of the chair of Wada's athletes' commission Beckie Scott and resign?

This is a crisis that has the potential to fracture sport's entire anti-doping community, leave Wada diminished and cast fresh doubt on the validity and credibility of sport's greatest events.

- Published21 September 2018

- Published21 September 2018

- Published20 September 2018

- Published19 September 2018

- Published19 September 2018

- Published17 September 2018

- Published15 September 2018