Ian Roberts: The double life and singular purpose of a rugby league legend

- Published

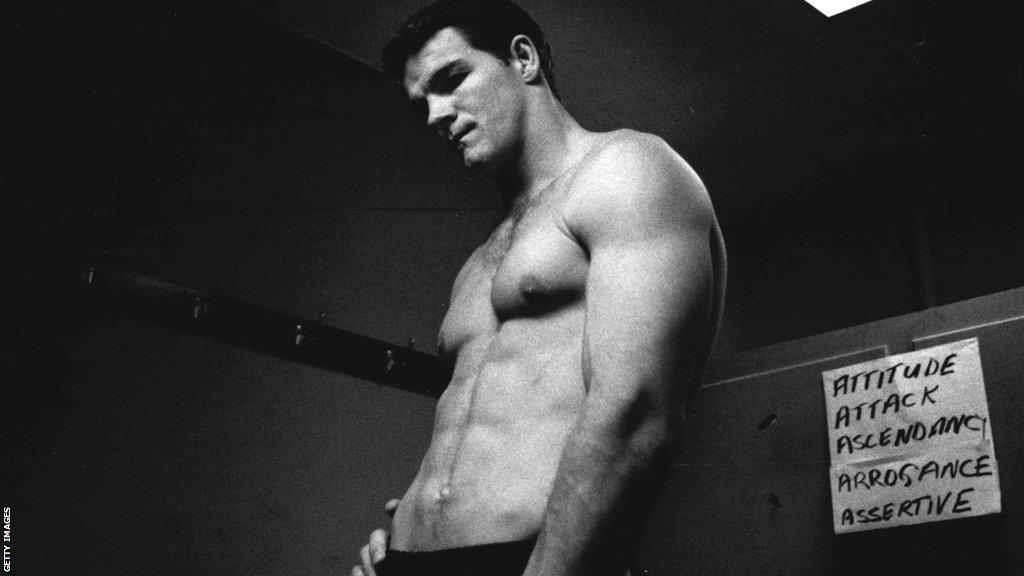

Roberts became the highest-paid player in Australian Rugby League when he controversially switched from South Sydney Rabbitohs to Manly Sea Eagles in 1990

It was as if Mick Potter had disappeared.

One instant, the St George full-back was bolting upfield, arms pumping, surging towards open space.

The next, he was gone. In his place, there was only a cloud of dry dirt and a mound of tangled limbs. , external

As the dust settled, the cause became clear. Ian Roberts, 6ft 4in tall, 16st strong, stood over Potter. He barked at his floored opponent to get to his feet and play the ball. He turned to his Manly team-mates and exhorted them to follow his lead.

Australian rugby league in the early 1990s was an unforgiving school of hard knocks, tough men and scant sympathy.

And Roberts sat right at its apex.

An Australia international, a State of Origin regular, he was the highest-paid player in the country after moving from South Sydney Rabbitohs in a deal that earned him a reported quarter of a million dollars a year.

"My work-rate was always really high," Roberts tells BBC Sport as he looks back more than 30 years on.

"I had a high tackle count and big yardage play in terms of hitting the ball up.

"I could offload and I had some other skills as well - I was good under a high ball.

"By the time I was playing for Manly, I was much more of an enforcer.

"I had matured in terms of my own confidence and I became renowned for my aggressive style of defence."

But there was a different side to Roberts.

In the boot of his car, next to his kit bag, was another holdall. Inside, instead of the boots and muddy shorts, might be a neat navy-style jacket and a pair of silk parachute pants.

After his Saturday afternoon on the pitch, Roberts would spend Saturday night on Oxford Street, Sydney's gay quarter.

"There I found the people I admired most," Roberts says.

"The trans people, guys doing drag, just gay people on the street doing their thing, living life and living large.

"I used to be in awe of these people and their sense of strength and power.

"But it used to really mess with my head. I would feel such a fraud, because I would be pretending to be this other person."

The pretence was nearly over, though. Roberts' sexuality was, in his words, the "the worst-kept secret in rugby league".

The drip-drip of leaks were about to turn into a watershed, not only for Roberts but also his sport and country.

Roberts' story broke in Australia. But it was formed and fermented in England.

Roberts was born in Battersea in 1965. He lived in London for a couple of years before his father Ray, unsettled by the city's increasingly cosmopolitan population, moved his young family to Australia.

They settled in a small government-provided house in Maroubra, then a working-class suburb of Sydney, close to the sea. But the change of scenery did little to change the undercurrents in his upbringing.

"There was plenty of love in my family," explains Roberts.

"But the reality of it is I grew up in a household where there was a lot of racism, and misogynistic and homophobic language.

"It was very clear in my house that being same-sex attracted was not something to be proud of or spoken of.

"I remember, as a seven year-old, sitting next to my dad watching a documentary show on ABC called Chequerboard. It showed two men kissing. It was the first time two men had kissed on Australian television.

"I remember thinking 'that is what I am like'. But my dad, sitting next to me, said 'that makes my skin creep'."

It set the tone. Ray didn't ask. Ian didn't tell. And, for a while, an uneasy silence survived.

Roberts rose fast in rugby league. He made his debut for South Sydney as a 20-year-old, skipping straight from feeder club to first team, bypassing the under-23 and reserve set-ups that usually toughen up prospects.

The following season he was named as the best prop in the Australian game, an award usually reserved for a grizzled veteran.

However, Roberts was finding that keeping two lives separate was not as easy as two bags in the boot.

The betrayal of himself nagged, whether he was in a nightclub or representing his rugby league club.

"Taking on those preconceptions about gay men - that they were weak, that there was something homoerotic about any desire to play contact sport - absolutely drove me on in the way I played at times," remembers Roberts.

"I felt like I had to be more of a 'man', more of a menacing presence. I couldn't be brave in the way some gay men were in their lives, so I put it into a physical bravery on the pitch."

Roberts at a State of Origin training camp with New South Wales in January 1994

In dressing rooms around the league, Roberts' claims that it was the music scene which drew him to Oxford Street were bowing under disbelief.

At his own club, South Sydney, Roberts could live with it.

"Some of the guys would joke around, but I was never made to feel uncomfortable," he said.

Playing alongside team-mates he knew less well for New South Wales or Australia, men whose prejudices hadn't been surpassed by the bonds of playing together, was harder.

But a brief stint back in England was the hardest.

With any work permit issue eased by his heritage, Roberts turned out for Wigan for a few months of the 1986-87 season.

"I had a wonderful time in Wigan and I met some wonderful people, but I became very aware very quickly that that changing room was a very homophobic place," says Roberts.

"I'd come from Sydney where there were showers after the game. But in England both teams would jump into a big bath together.

"Everyone would be heckling each other in there, carrying on like a bunch of gay men, but there was this real clash.

"There were some awful conversations about gay people. It was very unsafe, almost dangerous. It felt close to violence."

Disconcerted by what he heard, Roberts didn't investigate whether Wigan had a gay scene. He didn't venture into those in Liverpool, Manchester or London.

He played it straight as team-mates and opponents, fuelled by fears of a dawning Aids epidemic, voiced their hate.

So when Justin Fashanu came out a few years later - becoming the first openly gay professional footballer at the top of the English game - Roberts watched on from afar with interest.

"We didn't have any internet or smartphones back in 1990," says Roberts. "It was all through papers, radio, TV or the gay rags we had.

"Justin Fashanu was a hero of mine. I was in awe of him, completely blown away by his bravery.

"And then to see the backlash he got from fans, to see him brutalised by the English press…

"I felt beaten down myself by the way he had been treated. I didn't come out for another four years."

Roberts started all three Tests of Australia's famous series win over Great Britain in 1994

By the time of Fashanu coming out publicly, Roberts had done so privately though.

On a break from her shift working as a cleaner for Australian airline Qantas, Roberts' mother had heard two colleagues, unaware of her family link, laughingly spread an untrue rumour that Ian had been caught by police having sex in public with another man.

Roberts' parents had been able to ignore the occasional taunts from the stands. But this, out of a crowd context, in their own workplace, to their face, was different.

Roberts was summoned to the family home. Unsure why, he walked into a funereal atmosphere. His mother was in tears. His father was terse.

"My dad retold the story and said 'we just need to hear you say you are not gay, and that is good enough for us'," says Roberts.

The demand hung in the air for a moment. Roberts stared vacantly into the television. And then, frustrated and tired, he told his parents the opposite.

"My dad's first words were: 'But you play footy, you play for Australia.' That was where his head went."

Roberts didn't speak to his parents for 18 months after that day. During those months, as he moved from South Sydney to Manly, he thought about making a public statement on a personal truth.

Instead, concerned about the further pain it would cause his parents and then shocked by the reaction to Fashanu's coming out across the world, he stayed quiet.

It took another trip to England to finally complete Roberts' journey.

Australia's tour of Great Britain in 1994 was the Kangaroos' last great expedition, a sprawling 18-game itinerary with three Tests against Great Britain at its heart.

Roberts' partner Shane, the man inside the over-sized sea eagle mascot costume on Manly matchdays, travelled over to watch.

Great Britain took a surprise victory in the first Test with Jonathan Davies dummying, darting and diving in for one of Wembley's great tries.

Australia emphatically won the second with a thumping 38-8 victory at Old Trafford.

An in-form Roberts had started both. But a phone call to his Leeds hotel room in the days running up to the Elland Road decider filled him with doubt.

It was from the coach, Bob 'Bozo' Fulton.

Fulton, a legendary Australia player now coaching his country, needed to see Roberts in person.

"You never get that call unless you are getting dropped," says Roberts.

"So I went up in the lift to this penthouse suite where Bozo was staying. The door was a little ajar and I could see Bozo was pacing up and down.

"I went in and sat down, and he was still walking up and down. He was really serious. I was getting worried something had happened at home.

"Finally he stops and says 'How do I say this? Shane can't stay with you in your room.'"

Shane wasn't. Contrary to a report to the team management, he, just like the other players' partners, was staying in a separate hotel.

"Bozo was so relieved. 'Mate, I'm so glad. That's great. That's all I have to say.'

"I found out after that it had been a big thing. The team manager hadn't been willing to talk to me about it, so it had fallen on Bozo, who had never mentioned my being gay.

"It was such a pure moment for acceptance for me, to be validated as a human being and, as I walked out, I thanked him.

"He just said 'All good Robbo. All good.'

"There was so much going on in that conversation beyond the words. When you have those awkward conversations, when you own it, it takes all the weight out of it."

Roberts started the third and final Test. Australia won. Before he returned home, he gave an interview that introduced the world to Shane and himself.

He was Australia's first openly gay player in top-level rugby league. Now, nearly 30 years later, it remains a club of one.

"I felt like I could breathe out properly for the first time in a long time," says Roberts.

"It took the ammunition out of peoples' guns. You gain a bit of respect from people. When you have taken ownership and are comfortable with yourself, there is a power in that and other people can sense it in you."

For his team-mates at Manly, who already knew Roberts' sexuality, it was a rallying call.

"It was kind of a bonding moment for us. They were my tribe and my people, and it almost felt at times like they were trying to protect me," says Roberts.

"My experience was so different to Justin's - I was embraced.

"I had this persona of being an aggressive player, a guy who could handle myself on the pitch - and I could. My coming out challenged people's preconceptions of gay men.

"There were elements of pushback - of course there were - but if I knew what I knew now I would have come into top-level rugby league as a gay man."

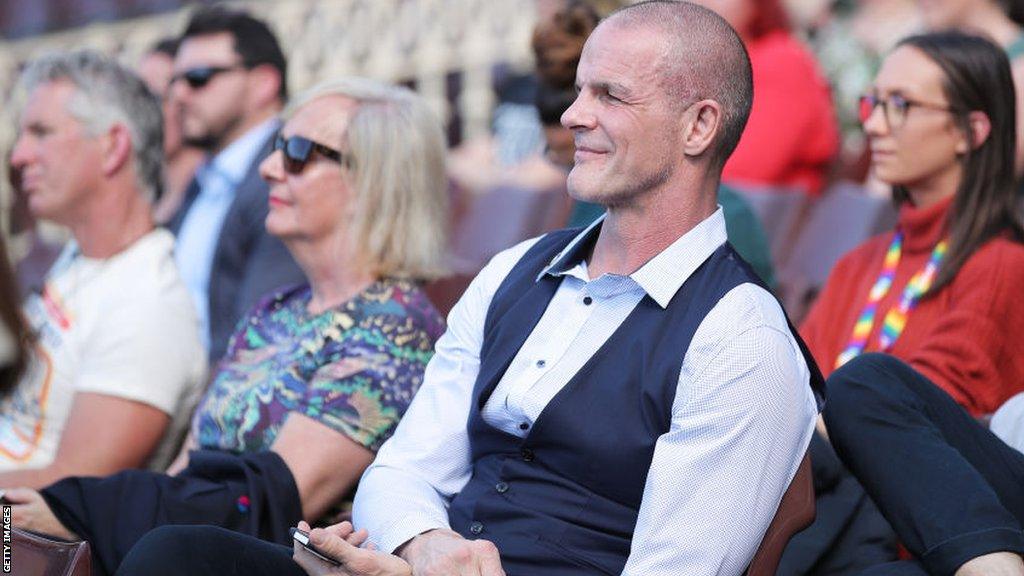

Roberts, now 57, is all about the power of those conversations, big and small.

Roberts, who has moved into acting after retiring from rugby league, lives in Sydney with his long-term partner Dan.

He is on the board of Qtopia, Australia's first LGBT history museum that will launch later this month in Sydney and feature commemorations of the past and celebrations of the present.

Sport will be part of it. In Australia, as in England, it is often how a nation's story is narrated.

Roberts has seen it in rugby league.

In the run-up to Australia's public vote for marriage equality in 2017, a performance by American rapper Macklemore of his anthem 'Same Love' at the NRL Grand Final, external divided sides of a debate.

Last year the refusal of a clutch of players at Roberts' old club Manly, external to wear specially designed Pride shirts did the same.

Roberts has seen it in other sports, in the way footballer Josh Cavallo and diver Matthew Mitcham - both fellow Australians - have told their truth and the reaction they received.

And he has seen it close up.

Roberts' father Ray died in December 2014, but not before making peace with himself and a son he had thought too much of an Australian, too much of a sportsman, to be gay.

"My dad's journey was quite remarkable. By the end he was a champion, such an ally," says Roberts.

"An interviewer once told him that he must be very proud of me.

"Dad said 'I am equally proud of all my children, but I will say that I am so grateful that one of my sons was gay because I finally saw the world as it really was'."

Roberts' story is a story of Australia, of England, but also of everywhere.

Do more expensive AA batteries last longer? Sliced Bread is charged up to find out

Why has Bad Education made a comeback? Jack Whitehall tells all about the cult sitcom