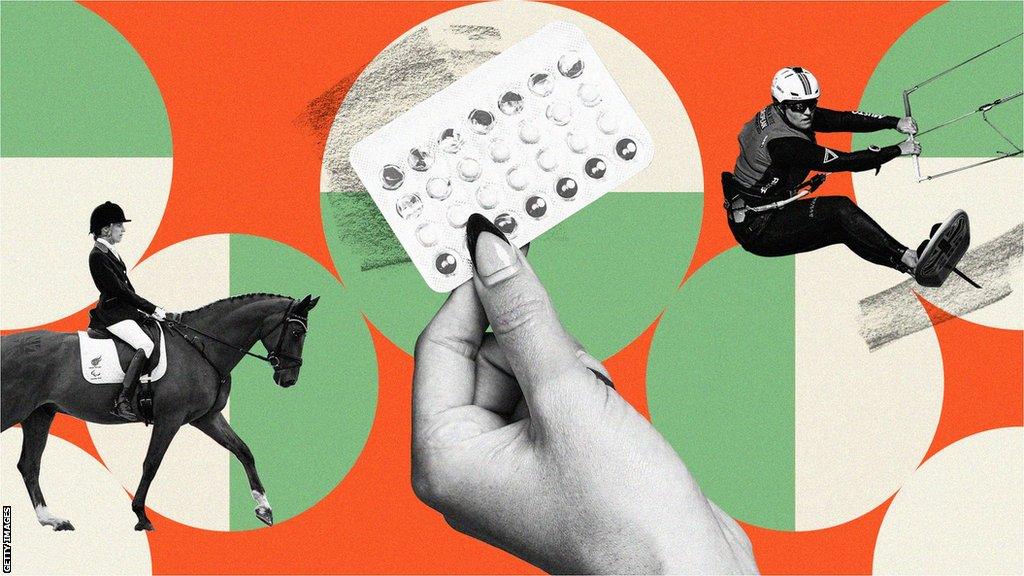

BBC Elite British Sportswomen's Study 2024: Sportswomen discuss their use of the contraceptive pill

- Published

There is a pill that you feel supports your athletic performance.

You also worry it makes you feel a bit low, you are not 100% sure of the research behind it and feel a bit strange about putting synthetic hormones into your body.

Would you take it?

This is the dilemma faced by some sportswomen when it comes to contraceptive pills.

A quarter of respondents in a BBC Sport study of elite British sportswomen said they take a contraceptive pill specifically to control the impact their period has on their performance.

Many athletes spoke about using the combined pill to time their bleed so that it does not interfere with training or competition.

British Sailing Team athlete Lily Young used the pill in this way, but says she feels research around how to take it "is a bit, not confirmed".

The main purpose of the combined pill is to stop pregnancy and hormones are used to achieve this.

Patients usually take the pill for 21 days, then have a break for seven days, which brings on a bleed.

Young used to skip these breaks, taking the pill continuously for up to three months at a time.

"I think they're never quite sure on how long to take it for," the 25-year-old says.

"They [medical professionals] seem to say no longer than three months back-to-back is a good place."

She adds: "I try to have as few periods throughout the year as possible.

"We go out on the water for long periods of time and wearing a tampon - I don't like it that much.

"I always try to plan by taking the pill back-to-back for three months at a time sometimes, to get rid of any of those symptoms happening.

"I never feel quite the same on my period. I always feel a bit hot when I try to work out."

'I'm never sure what to believe'

Almost two-thirds of respondents in BBC Sport's research said their performance was affected by their period, or that they have missed training or competition because of their period.

Respondents said they suffered cramps, felt sick or even fainted as a result of their periods. Just over half said they felt comfortable discussing their period with coaches.

Eventually, Young decided to move to the Mirena coil, which is inserted into the uterus and releases the hormone progestogen to prevent pregnancy, and which can make periods lighter, shorter or stop entirely.

"I did have to think about it because making changes to the body, especially being an athlete, you don't want to do it too close to anything important," she says.

"I'm never quite sure what to believe or what's the right thing to do. I'd been on the pill for seven years or something - quite a long time.

"I was getting a bit anxious that maybe that wasn't good, taking a hormone tablet every day for seven years. [But] I know a lot of people do it."

BBC Sport asked the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) - the government agency that regulates medicines - whether Young's use of the contraceptive pill is considered safe.

The MHRA response said there was no "maximum duration of use" for Microgynon, the pill Young used, adding that "off-label prescribing" - in Young's case, taking the pill for three months without a break - is legal and "at the discretion of the prescriber".

It added: "The MHRA can only ensure the safety of a medicine when it is strictly used according to the provided product information.

"Like all medicines, the combined oral contraceptive pill comes with both risks and benefits.

"It is important to discuss with your prescriber or healthcare professional whether this medicine is suitable for your individual needs, considering factors such as long-term use and dosing regime, and carefully weighing its potential risks against benefits."

Lily Young competes in kitefoil - a new event for the Paris 2024 Olympics

Manchester Metropolitan University professor Kirsty Elliott-Sale - a leading expert on elite athletes' use of hormonal contraception - works with sportswomen to "myth-bust", educate and help them understand the impact it can have on performance.

Professor Elliott-Sale says "there's nothing wrong" with sportswomen using hormonal contraceptives to manage menstrual cycle symptoms.

She adds that it is important to be informed about all interventions that could help, so athletes do not "swap one set of symptoms for another set of side effects".

"I'll ask [athletes] why they use that particular type of hormonal contraception and they say, 'Oh, that's just the one the GP gave me'," she adds.

"If they had gone in and said they were an elite athlete or they had had access to a sports medicine doctor, they might have ended up coming out with an entirely different one - one that's better suited to their sporting lifestyle.

"When the athletes don't know what to ask or what to tell, and the doctors don't know what their situation is, you can easily end up with a mismatch. Nobody is at fault."

Professor Elliott-Sale's advice might have been useful for eight-time Paralympic champion Sophie Christiansen, who had the pill suggested to her by a doctor early in her equestrian career.

"I didn't really know what my options were, and was shy about taking it because at 20 I wasn't sexually active yet," Christiansen explains.

"I compete in white and [there was] always the fear of not knowing if I was going to leak on my white jodhpurs."

'It wasn't worth it'

Although there is still plenty of work to be done, in recent years there has been a rise in studies on the impact of sportswomen's menstrual cycle on their training and performance, including research on increased risk of injuries.

In BBC Sport's study, a quarter of respondents said they had experienced a link between their menstrual cycle and injury.

One anonymous athlete spoke about taking the pill after she tore the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in her knee while she was on her period in 2022.

There have been calls for more research on why this injury seems to be more prevalent among female athletes, with high-profile athletes such as Euro 2022-winning captain Leah Williamson and England team-mate Beth Mead having previously torn their ACLs.

Some of this research focused on whether the menstrual cycle and hormones contributed to the risk of an ACL tear.

"After I tore my ACL, I started taking the pill because I so wanted to make sure that I wasn't getting that oestrogen release every month, that I was like, 'If I can stop that, or take something away, I'm less at risk of damaging my new [ACL] graft'," the anonymous athlete said.

"I started doing that, then realised that was not the right thing to do. I got really painful periods when I did then have a break on it.

"It wasn't worth it. I started off [taking the pill] continuously, then I had a deload week so I was like: 'OK, I'll come off it this week because I'm not going to be training as much, not pushing my knee as much.'

"It gave me more confidence in my knee, [but] I definitely felt a lot lower. A lot snappier and more anxious. The combination of factors made me realise it wasn't really worth being on it."

Professor Elliott-Sale says that increasing awareness has led to "a lot of negativity associated with the menstrual cycle", adding that currently "there isn't the research evidence out there to suggest you're going to get an ACL injury in a particular phase of the menstrual cycle".

"The truth of it is, if you look at elite level, medals have been won on every day of the menstrual cycle, medals have been won by pill users," she continues.

"We've gone from never speaking about it to it being our everything. I think we need to course-correct back into the middle."

Athletes Dina Asher-Smith and Jazmin Sawyers are among the sportswomen who have called for more women-specific sports science research in recent years.

Professor Elliott-Sale agrees that "historically, sportswomen have been let down by a lack of research" and she is eager to use her work to help athletes find the best hormonal contraception for them - but there is an issue.

"When researchers ask elite athletes to take part in research, their answer is they would love to take part but feel that they are too busy to fit it in," she says.

"We know they're very busy but if we do the research on non-elite athletes, it doesn't translate to them. Elite athletes are extraordinary.

"If elite female athletes want research for them, we've got to find a way to enable them to be participants in these studies."