The drama, pride and tragedy of the first F1 race in Africa

- Published

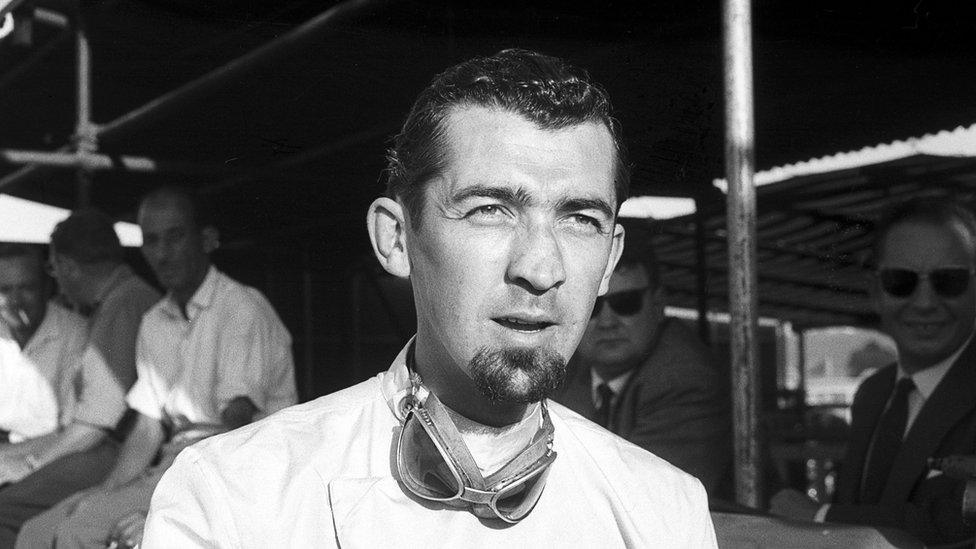

The intensely patriotic Moss was desperate to be Britain's first F1 world champion

The F1 season is getting under way again in 2021 with the Bahrain Grand Prix. Over the winter break, the head of F1, Stefano Domenicali, made mention of a desire for Formula 1 to return to Africa - to make it a true World Championship.

F1 has not been to Africa since 1993, but before that there were a number of exciting and dramatic races held in the continent. This is the story of the first of the first of those - the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix.

The context

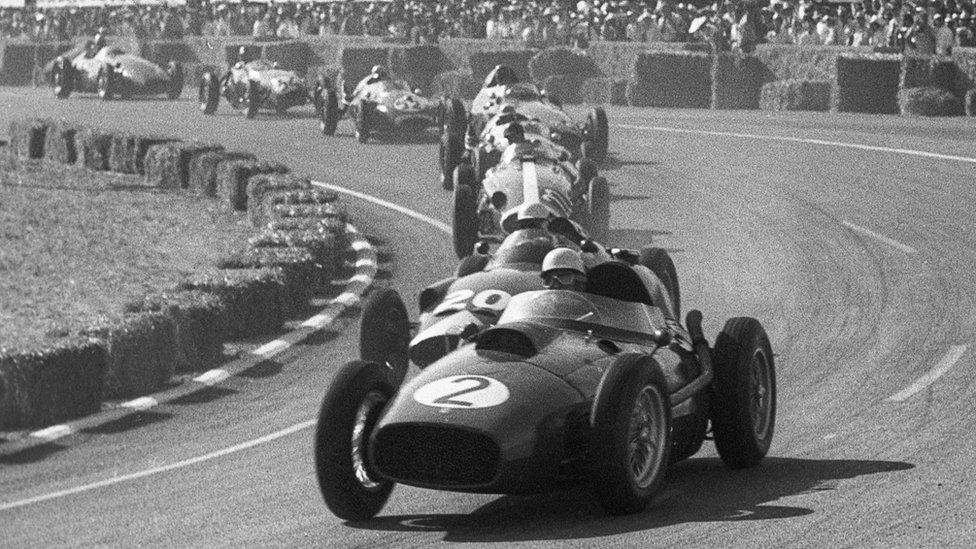

Phil Hill was designated to be Ferrari's "hare" and push the Vanwalls into breaking - even if it cost his own car

What was certain going into the last round of the 1958 World Championship was that it would be won by a British driver for the first time.

Between Vanwall's Stirling Moss and Tony Brooks and Ferrari's Mike Hawthorn and Peter Collins, British drivers had won all but one World Championship races that season, the exception being Maurice Trintignant's freak triumph at Monaco. (There was also an Indy 500 that counted to the championship that year, but life's too short to get into that now, external).

The title had nearly been decided at the Portuguese Grand Prix two races before, when Moss had dominated and Hawthorn had spun on his last lap, having to get out of his car and try to push-start it. It was only thanks to some advice from Moss as he passed Hawthorn on the slowing-down lap - "push it downhill - you'll never start the bloody thing that way!" - that Hawthorn finished at all.

Even more extraordinarily, a marshal had seen Hawthorn turn his car round and thought he had done it against the flow of traffic on the circuit. This was against the rules and Hawthorn was threatened with being excluded. Moss, summoned as a witness by the race organisers, insisted that Hawthorn had performed his turn off the circuit on an escape road.

Hawthorn was reinstated. Had Moss not supported him, Hawthorn would have been disqualified and Moss would have been world champion there and then.

But he did and so he wasn't. Instead, going into this last race, Hawthorn had 40 points to Moss' 32.

The scoring system at the time only counted their best six results from the 11 races meaning that Hawthorn could only improve his total if he finished second or higher. But if Hawthorn finished third or lower, a win and fastest lap for Moss would put him on 41 points - and give him the title.

Qualifying

Fortunately for Hawthorn, Gendebien was not superstitious

Hawthorn's mood on arrival at the Ain-Diab circuit was immediately darkened when the dust sheets were pulled off his Ferrari and he saw the number 2 painted on it.

That number had been the one used by both his team-mates Peter Collins and Luigi Musso when they had been killed in races earlier that year.

Hawthorn insisted on swapping numbers with Olivier Gendebien. Fortunately, the Belgian agreed and Hawthorn's mood improved - to the extent that on the Saturday he took pole.

Moss was only one tenth of a second behind him, however. At the time, the grids were not staggered, so Moss was starting right alongside Hawthorn, right in the middle of the track.

To his left was his talented young English team-mate - not Brooks, who had only qualified 7th, but Stuart Lewis-Evans, a rising star at Vanwall in the days when teams could run three or more cars.

The race

Mike Hawthorn drove at Morocco as he had all season - conservatively, but doing just enough

In order to prevent Hawthorn getting the second place he needed, Vanwall decided to deploy team tactics to full effect.

They had three cars - their plan was for Moss to dash into the distance and Brooks and Lewis-Evans would block the Ferraris, keeping them at bay.

If the plan was successful, Hawthorn could finish no higher than fourth. That would mean the result would not be one of his season's best, and Moss would triumph.

And to begin with, it worked brilliantly. Then as now, some races could be decided on the run to the first corner - and the winner in Morocco was no exception.

Moss and Lewis-Evans shot off the grid, leaving Hawthorn trailing badly.

But quickly, Ferrari got tactical themselves. They sent Hawthorn's team-mate Phil Hill to go all-out in pursuit of Moss, while Hawthorn more steadily guided his car round.

Unlike now, cars were delicate and prone to breaking. (Indeed, this was the reason that drivers could only count their best six results). They had to be driven carefully and precisely - one slipped gear could blow the whole thing to pieces from within. If Hill put Moss under enough pressure, he might make a mistake and be forced to retire.

Instead it was Hill who made the mistake. He pushed too hard and briefly went off the circuit on lap three. Moss scampered off into an unchallenged lead.

The Ain-Diab circuit was built on the main road between Casablanca and Azemmour

But behind him, Vanwall's plan was falling to pieces. Lewis-Evans had already been dropping back by the end of lap one. Brooks was up to third, in front of Hawthorn. Moss needed him to stay there.

He didn't. Just before half distance, Hawthorn slipped out from behind Brooks - known as the "flying dentist" because of his pre-racing career - and into a crucial third.

Brooks tried to keep pace. But in doing so - as Ferrari had planned - his engine broke.

Moss was romping away and doing everything he could. But Hill slowed and let Hawthorn through and into that crucial second place.

Then, a desperate situation for Vanwall turned to tragedy.

Lewis-Evans suffered the same engine seizure that had afflicted Brooks. But whereas Brooks had walked away from his vehicle unscathed, Lewis-Evans' Vanwall spun with its rear wheels locked, sending him off the road and causing the car to burst into flames.

Lewis-Evans climbed out, but he was very badly burned.

Up front things were now settled. Moss was nearly a minute and a half ahead, and had also got the fastest lap.

But Hawthorn only needed to get home, and had Hill as a rear gunner to fend off anyone else. But with both Vanwalls out, he was untroubled.

Moss took the win, but not the title. Hawthorn was 1958 world champion by a single point.

Aftermath

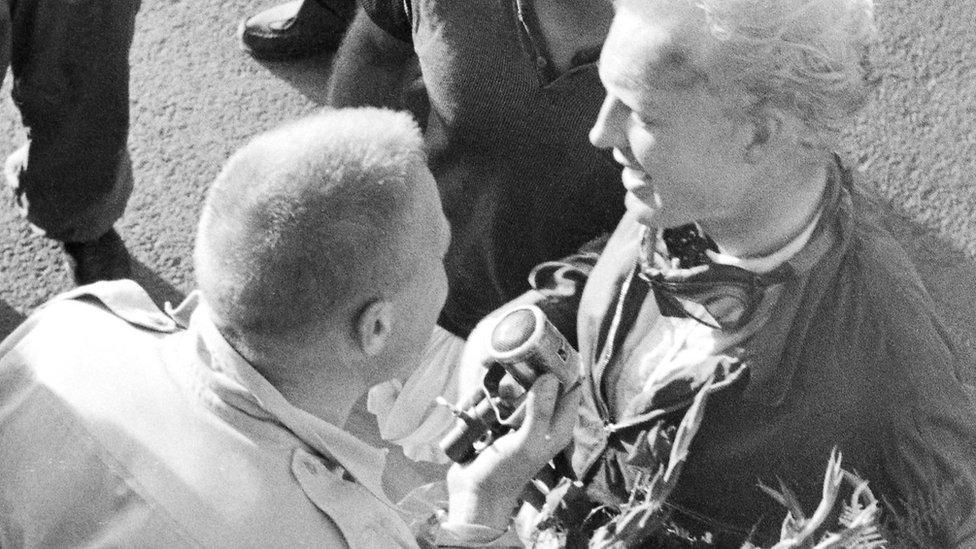

Before Lewis-Evans' death, no-one had been more than slightly hurt in a Vanwall

The headline in Motor Sport magazine summed the race up perfectly afterwards: "Moss is perfection - but it is not enough."

"My congratulations were genuine, but I could not hide my deep depression because of poor Stuart's crash as well as my own disappointment," Moss reflected after the race.

"It really did hurt."

Worse was to come.

Lewis-Evans had been rushed back to England in a private plane by team boss Tony Vandervell. But despite the best efforts of specialists at East Grinstead's Queen Victoria Hospital, he died of his burns injuries eight days after the race.

Devastated, Vandervell closed his team. They had just won the first ever Constructors' Championship.

Stunningly, the drivers' champion also never raced again. Hawthorn surprised everyone by announcing his retirement from the sport, even though Enzo Ferrari had told him to "name his price" to stay on.

He said he wanted to quit while at the top - though the death of his close friend and team-mate Collins earlier in the season had surely been a factor.

But no-one would ever really know, because only two months later Hawthorn was dead - killed in a road accident outside the English town of Guildford.

Hawthorn (right) quit the sport at the top, but never got the chance to enjoy a life away from racing

And the 1958 Moroccan Grand Prix was not just the end of a season - it was the end of an era.

Everyone assumed that with his two main rivals having left the sport in successive seasons, Moss - four-time runner-up - would finally be champion in 1959.

But he could not keep up with technology, in the wrong teams at the wrong time, as races came to be dominated by cars with engines placed behind the driver, not in front.

Eventually in 1962 Moss signed a contract to drive for Ferrari, who had dominated the previous season. Surely he would finally get the title he had been so close to winning in Morocco?

As it turned out, no. Moss was so badly injured in a non-championship race before the season started that he never appeared.

His career was over. What Moss and Ferrari might have achieved together remains one Formula 1's great "what if" questions.

"If Stirling had put reason before passion, he would have been world champion," Enzo Ferrari said after Morocco 1958, reflecting on the sportsmanship Moss showed towards Hawthorn in Portugal.

"He was more deserving of it."

This story was first published in February 2020