Shura Kitata on what it took to beat Eliud Kipchoge in the London Marathon

- Published

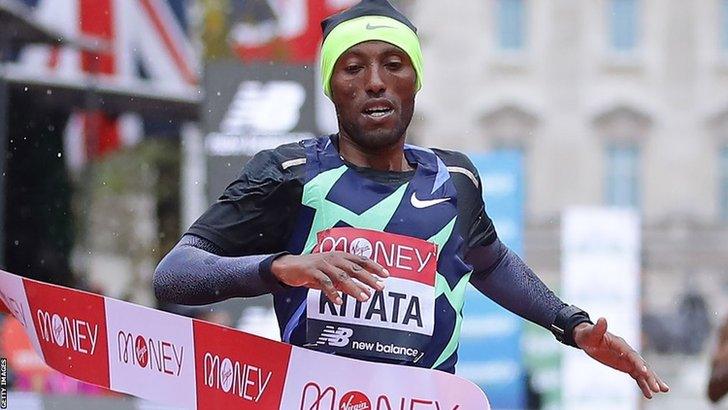

Shura Kitata crosses finish line at 2020 London marathon

What does it take to beat Eliud Kipchoge, the only man to ever run a marathon in under two hours?

Extreme training, talent and - in the case of London marathon champion Shura Kitata - a good breakfast.

Last year the Ethiopian finished fourth in the English capital, a race won by Kenya’s Kipchoge, with Kitata tweeting later that he only had fruit for breakfast and was running on empty - “I felt my stomach touching my back, [I was] super hungry, external” – after 35km.

This year, having learned from his mistake, he fuelled up before the race.

"I ate everything,” he told BBC Sport Africa.

“I had soup, bread, eggs and yogurt – everything that I could to boost my energy and it helped me keep my energy up and I was able to win the battle."

The battle was to unseat the man who has dominated marathon running since 2014 – world record holder and Olympic champion Kipchoge, 35, who was on a ten-race winning streak and eyeing a record fifth London title.

And for the first time there was a chink in Kipchoge’s armour as he finished eighth, later explaining that an ear problem affected him.

Tough conditions

Eliud Kipchoge competing in London 2020

The cold and wet conditions were not the best for distance running, with Kitata’s winning time of two hours five minutes and 41 seconds reflecting that, but the Ethiopian believes the weather gave him the edge.

"When I saw the rain I was excited because I had been training in heavy rain season in Ethiopia," explained his nation’s first male winner in London since 2013.

"One day I went to train in Sodere, a place outside the capital, and it rained so much that the town flooded and the coach had to come to my rescue.

"When the pandemic struck, I didn’t just stay at home. I was working with my coach for five months. It was not special because I beat Eliud Kipchoge, it was special because I worked hard."

Following the late withdrawal of fellow Ethiopian Kenenisa Bekele with injury, the anticipated duel with Kipchoge was never to be - with Kitata earning the headlines instead.

"Everyone was focussed on two athletes – Kipchoge and Bekele – and I didn’t get any attention," he pointed out.

"I told myself that I will prove to the world that there is another champion and this feeling is what made me able to sprint to the end with full confidence and energy."

Kitata may not be a household name but two runner-up finishes in London and New York in 2018 and a personal best of two hours four minutes and 49 seconds means he has earned his stripes in the often-brutal distance.

Quiet but confident

Those around him describe the 24-year-old as a silent but confident athlete.

"He is a humble, focussed, family-oriented man and the most outstanding thing about him is his confidence," his representative Hussein Makke told BBC Sport Africa.

"In London he believed in himself and coming into the race he didn’t care who was there and that helped him become the champion he is now. I hope he continues."

Introduced to athletics in school back in the Oromia region, Kitata’s talent has been groomed by coach Haji Adilo in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa since 2015.

Shura Kitata takes the lead at the 2020 London marathon

"He is the kind of athlete who is aggressive and is always trying to push himself as much as he can," added Adilo, who missed Kitata’s shock win after testing positive for Covid-19 just days before leaving for England.

"A man I used to run with from Kitata’s region brought him to my camp and asked me to take a look at him. We gave him a trial and he looked good but he needed to improve in endurance and speed.

"Within three months, he had improved so much we sent him to his first marathon in Shanghai."

Kitata has come a long way from his dreams of a white-collar job to joining the list of top talents from Ethiopia.

Born to farmers in a family of seven children, Kitata’s background of financial difficulty resonates with that of many athletes from East Africa.

"I loved studying and I wanted to be a doctor or a pilot but I come from a poor background and I had to leave school to help my parents at home in the farm," he narrates.

But despite his failure to achieve one of his stated aims, he is flying high nonetheless.

“I never thought that one day I would become a star and travel around the world,” he said. “This was the first time a prime minister had tweeted about me, external and my success. Because of athletics I am living a life I never imagined."

And the next aim for this father of two is simple - ending Ethiopia's two-decade drought in the Olympics' men's marathon.

"I will try to bring a gold medal for my country and also for my children to have as a memory - so they can one day say 'my father was an Olympic medallist'."