London 2012: Mo Farah gambling on Olympic double, says Mike McLeod

- Published

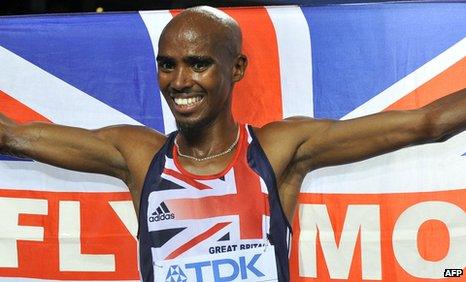

Farah won 5,000m gold after being pipped in the 10,000m in Daegu last year

Mo Farah's decision to go for double glory in London this summer is a major gamble, according to Britain's last Olympic medallist over 10,000m.

Mike McLeod, who ultimately won silver at the 1984 Los Angeles Games after being elevated from bronze because of a doping scandal, thinks it will be "very, very difficult" for Farah to win both the 5,000m and 10,000m titles.

"I would probably just go for one and put all my resources into that, but obviously with Mo he's got the bite of two cherries here. He's going to plan it very carefully," says 59-year-old McLeod, who remains heavily involved in grassroots sport in his native Newcastle as well as running his own printing business.

"He's got a plan so he must be capable of running the two events. It depends how hard the final is of the first event - that's the problem. If he's really stretched close to world-record pace, that could have an effect on him."

However, according to McLeod, the prize on offer should Somalia-born Farah win both events is to become "one of Britain's greatest ever athletes".

McLeod, who knows Farah and describes him as "a cheerful lad, pleasant, always smiling", thinks the 28-year-old will have learned from the bitter disappointment of being pipped on the line in the , external in South Korea last year. He responded on that occasion by taking gold in the 5,000m.

"He just went too early - he knew that," McLeod says of the first final. "If you go out too early you're just the pacemaker. And if you can't get rid of them, you've got to be bloody good to beat them.

"I think the lad who beat him was very quick and just thought, 'This is great, he's took off and I'm hanging on', and Mo just could not get rid of him. Whereas had he left it a bit later he possibly could have got the double."

That defeat will be indelibly burned into Farah's find, according to McLeod: "If I know Mo he's probably going to be working drastically on his speed and strength so that he can [lead from the front] and still out-kick them, but he'll have different tactics going into the race. There's plenty of plans you need."

Farah must deal with not only the pressure of being a double world medallist, but also the media interest associated with competing in his home Olympics.

Brendan Foster and Mike McLeod (right) had a series of 10,000m battles in the late 70s and early 80s

"Everybody will be expecting him to just walk on to the track and pick a gold up," says McLeod. "But it doesn't work that way. Mo's down to earth, though, and he knows that the medals are not on a plate. He knows he has to work very, very hard and he's aware of all the other athletes who will be watching his races on video.

"Mo's going to have a lot to do leading up to the Olympics. First of all he's got to be injury-free. I think he'll be out of the country for quite a while, training hard, and he'll just come in and try to keep away from the press.

"The press tend to hang medals around your neck - sometimes that can have a major effect on people. I just hope he doesn't look at too many press cuttings or the TV leading up to the Games."

So how does running at an Olympics differ from competing in other events?

"It affects people differently. I was quite nervous. But, on saying that, I was expecting to get a medal in Moscow in 1980 and I ended up tearing a hamstring in the warm-up area, and that was me gone."

In 1984 McLeod struggled even to make the team, "so there wasn't that much pressure for me to get a medal. But I was quietly working towards it, training very, very hard, getting the speed work in, all the repetition work".

That hard work paid off and he produced an outstanding display to cross the line third in Los Angeles. Following Finn Martti Vainio's disqualification for using anabolic steroids, McLeod was promoted to silver.

But that's still not good enough for the Briton, who remains angry that he was never given the gold medal following a later blood doping admission by Italy's Alberto Cova. At the time, blood doping was not a banned practice.

For McLeod, results should be changed retrospectively in light of new information. "I should be elevated to the gold because I was the clean person. There shouldn't be any time limits. They should still go back. It changes your life. There is a vast difference between gold and silver. It's sad."

As a victim of those who abused doping laws, McLeod's position is clear on the thorny issue of bans and their severity.

"When people are caught doping and it is proven they should be banned for life from all sports, to try to make a stand," he says. "But then you've got the human rights and lawyers coming in saying 'somebody's doctored his toothpaste' and all of these pathetic excuses.

"They should have a precedent right across the board: caught doping and you're out of sport for good."

- Published22 December 2011

- Published17 November 2011

- Published15 November 2011

- Published28 October 2011

- Published5 October 2011

- Published28 September 2011

- Published4 September 2011

- Published28 August 2011

- Published13 July 2011

- Published4 June 2011