When BBC Sport tried the 'whereabouts' drugs testing system

- Published

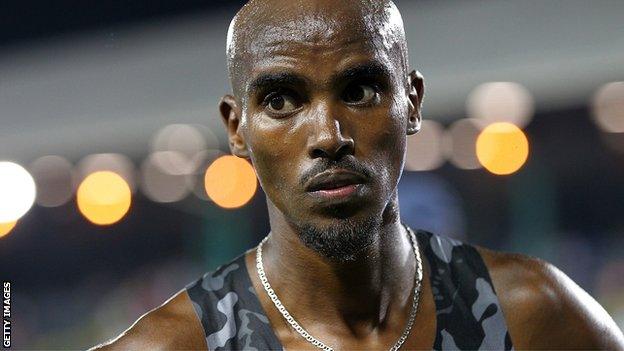

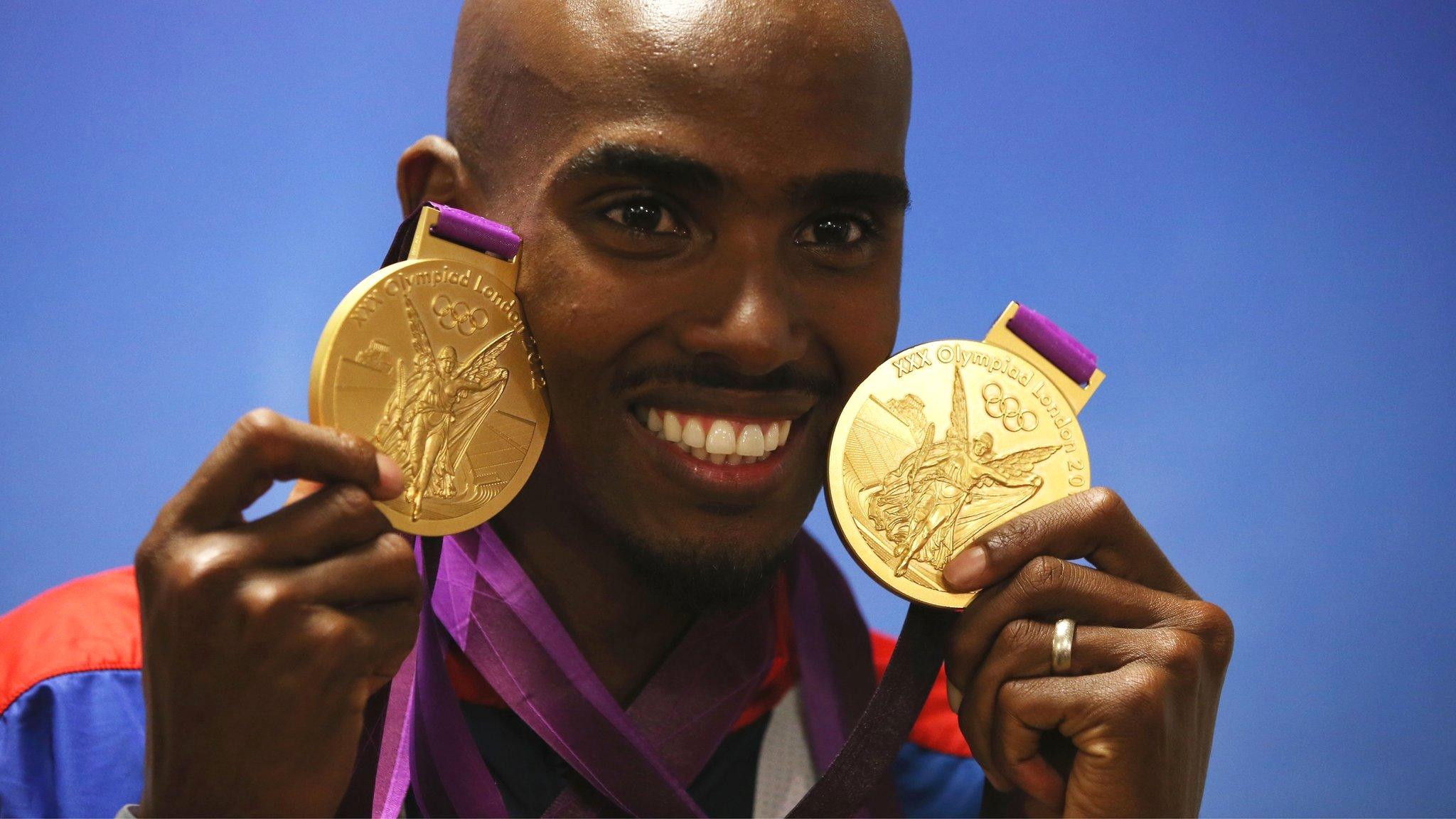

Mo Farah won gold medals in the 5,000m and 10,000m at London 2012

Nine UK athletes, including Mo Farah, missed drug tests in the year before London 2012, it has been claimed.

After the Daily Mail reported double Olympic gold medallist Farah failed to hear the doorbell when UK anti-doping (Ukad) officers called at his house, a number of his Great Britain team-mates told BBC Sport of their near-misses.

Olympic medallist Kelly Sotherton and 800m runners Jenny Meadows, Michael Rimmer and Lynsey Sharp all attested to how strict the requirements of the 'whereabouts' system are.

Sharp revealed how she spent one hour a day in a Boston cafe while on holiday for two weeks because the rented apartment doorbell didn't work, while Rimmer even suggests athletes are tagged to make it easier for the testers.

So how easy is it to miss a random drugs test? The BBC's chief sports writer Tom Fordyce recalls his month on the 'whereabouts' system...

You might think it was impossible. So did I. Which was why, back in 2011, I began a month-long experiment in which I was added to something called the National Registered Testing Pool.

This is the controversial heart of the fight against doping, the 'whereabouts' system that UK Anti-Doping uses to keep track of the country's 400 or so elite Olympians. Each athlete must specify where they will be for an hour a day, seven days a week, for three months in advance, as well as where they will be training each day.

If it sounds draconian, there is logic behind the imposition. Out-of-competition testing is far more likely to catch cheats than tests only taken at big events. To be effective, these tests must be unannounced. Hence the need to specify a window of opportunity.

Being someone who considers themselves relatively organised, I could envisage few problems doing it for just four weeks. That was to underestimate the detail required and the intervention of the real world.

Mo Farah angry at 'being dragged through mud'

On a computer programme called Adams (Anti-Doping Administration and Management System), each athlete must submit a mountain of information: their residence for every day in that month, whether home address, hotel or friend's house; their full training schedule for every day; where they will be competing - dates, venues, times - and where and when their one-hour slot will be.

The programme itself looks a little like Microsoft Outlook, albeit initially less intuitive and a little more fiddly. There is a clickable daily calendar, contacts section and area for direct messages.

Each athlete has access to a support officer who is available to help them 24 hours a day. This quickly becomes essential, because everything takes time. For every address you might stay at overnight you have to input full details - not just the name and street, but specific instructions - ring top doorbell, blue door on left, code for front gate etc.

If you spend your entire life in one place it wouldn't take very long. But sportsmen don't. Neither do sports journalists. In that month I was due to be in Southampton to cover cricket, Wimbledon for the tennis, some friends for a weekend away, a stag-do in London and a hotel or two for other work trips. That's a lot of addresses.

Then there are the spontaneous complications.

One morning my mum called, inviting me over for Sunday lunch. Among the things to remember when visiting home (flowers, better manners), emailing the drug-testers to give them her address did not come naturally.

So much for the theory. When the testers actually came, I almost missed them.

These are the bottles, complete with their lids and seals, that need to be filled when the DCO visits

Having worked until the early hours and been up in the night to comfort my then-three month old son, I slept right through the 6.30am doorbell.

Only my partner heard it. Had she too missed it, or had chosen to ignore it and stay in bed rather than opening the door, the DCO (doping control officer) would then have tried again every quarter of an hour.

My mobile was out of action, turned off in the hope of a lie-in. The DCO could not have called it anyway. Testing cannot be done without warning if your phone alerts you first.

Had I failed to respond to the doorbell's nudges for duration of my specified hour, it would have been logged in the system as a missed test.

As a result, that morning I noted two apposite lessons: one, install a loud doorbell, and two, make sure you can hear it anywhere in the house.

But I had made another error a few days earlier that might have been just as costly.

Due to interview hurdlers Dai Greene, Jack Green and Lawrence Clarke down in Bath, I decided to set off early to dodge the traffic on the M4. Which was fine, but meant I left at 7am - half way through my specified testing window.

Because I was sleeping in my own bed I didn't think about updating Adams - 7am didn't even feel that early. The only alarms going off were on my bedside table.

You could argue that those sorts of mistakes are much more likely when you are in the early stages of learning the system. With time, making such adjustments may have become second nature.

It was also easy to make a tweak. You could change that specified hour up to 60 seconds before it is due to start, by sending a text message, phoning a dedicated number or by going online and accessing Adams. There is now a smartphone app which makes it even simpler.

The education officers will even keep an eye on your Adams and send you a message if it looks like you've neglected to put the right information - for example, if you're off to France to represent Britain in a competition and haven't altered your schedule to reflect that.

The Brazilian Doping Control Laboratory will be active during the 2016 Olympic and Paralympics in Rio

Neither was my career in danger from my month in the testing pool. Had my reputation and future been dependent on getting even the smallest details right, perhaps it would have been an hourly priority. This, after all, is an athlete's chance to prove to the world that they are working their sporting wonders in a clean and fair way.

And yet. There were enough diligent, intelligent athletes I spoke to at the time who had either had close shaves or missed a test through an arbitrary change of circumstance for you to understand how it could happen.

An injury which led to an emergency trip to the physio's. A child falling ill. A big exam the next day. Where there is stress and panic, logic can get lost.

Me? I could understand why the system is as it is. It's a tough regime to live under, but if we can't trust the sport we are watching, we may as well give up.

- Published18 June 2015

- Published16 June 2015

- Published10 September 2015

- Published8 February 2019