Goldie Sayers: British javelin thrower retires with 'deep sense of injustice'

- Published

GB Javelin thrower Goldie Sayers: The best moment of my career was stolen

Retirement is supposed to signal a full-stop. The end of one life, the start of another. A sense of satisfaction, a sense of closure.

There should be no limbo. But for Goldie Sayers - the 11-time British javelin champion and three-time Olympian who announced the conclusion of her athletics career on Wednesday - the wondering and "what ifs" will follow her into the future.

After eight years of waiting, Sayers was told in September that she was being retrospectively awarded Olympic bronze from the 2008 Beijing Games. Mariya Abakumova, the Russian who had finished second and who Sayers had always suspected of cheating, had failed a doping retest for a banned steroid.

Sayers, now 34, celebrated with a coffee in Waitrose with her mother, Liz. And then the limbo began: Abakumova appealing against her disqualification, the legal process slowing to a crawl, no medal in the post and no idea of when any of it will end.

"Initially I was just really happy," explained Suffolk-born Sayers. "I'd been chasing something that had eluded me and then all of a sudden, driving down the M11, I had it.

"But actually now I'm much angrier about it - and I'm not an angry person at all. There's a deep sense of injustice.

"I was desperate to draw a line under my career and move on because I think endings are important - but at this rate I'll be drawing my pension before I get an Olympic medal."

London Grand Prix: Sayers breaks GB javelin record

Sayers is not alone. The International Olympic Committee, external (IOC) has now caught 111 athletes with retrospective tests from the 2008 and 2012 Olympics, a welcome epidemic of late justice that has brought with it its own chaotic tail.

Because so many of those who fail retests routinely appeal to the Court for Arbitration for Sport, external (Cas), regardless of evidence or ethics, those clean athletes promoted in their wake are left somewhere between regret, exasperation and hope: swindled out of their defining sporting moment, denied the financial rewards that a medal would have brought, left hanging by a system that is stumbling towards a cleaner future while trying to mop up the mess of the past.

"It's all about the moment for me," says Sayers, now 34. "None of the other stuff that would have come with it - sponsorship, profile, the actual medal itself - matters in the same way.

"I'd love to be able to transport myself back to standing on an Olympic podium, but I won't ever be able to do that. You have had the greatest moment of your life stolen from you.

"Javelin is literally one moment. The whole of my run-up took 4.45 seconds, the throw itself took 18 hundredths of a second, 80% of my speed of release came from the last hundredth of a second.

"When your timing is right, and you're mentally and physically at one with your javelin, time effectively stands still. Those moments become exaggerated. The whole world makes sense in that instant.

"If you've seen the film Limitless - where Bradley Cooper takes a pill and the whole world slows down, and he can problem solve and make things happen - that's what javelin feels like when your timing is on.

"That's what you miss: the flow through your body, everything separating and moving as one. I miss time standing still.

"And it's about sharing that moment with other people. I remember celebrating what I knew was a personal best and British record, over the road from the Bird's Nest stadium. My mum, a family friend who'd come over to support, my coach Mark, Steve Backley and his mentor John Trower, Seb Coe. There were a lot of people in that hotel bar.

"Sharing that moment with all of them, that nearly moment, I was excited, and there was a sense of pride of seeing a plan through. But it would have been incredible, I know, if I had been standing there celebrating as an Olympic medallist - because it would have meant so much to all those people, not just me."

Rooney hopes to get 2008 medal at Olympic stadium

There are nine British athletes from the 2008 Olympics in this strange purgatory: the men's 4x400m relay squad of Andrew Steele, Robert Tobin, Michael Bingham and Martyn Rooney; the women's 4x400m team of Christine Ohuruogu, Kelly Sotherton, Marilyn Okoro and Nicola Sanders; and Sayers.

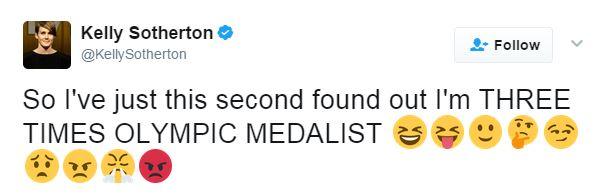

Sotherton, who retired five years ago, is owed two medals - one from the relay, one from the heptathlon, where she initially finished fifth before retrospective bans removed Lyudmila Blonska of Ukraine and Russia's Tatyana Chernova.

Kelly Sotherton tweeted this after finding out about her upgraded heptathlon medal

No-one knows when those medals will arrive, or how - prosaically, in the post, as some have in the past, or awarded at a special ceremony at a future athletics meet, maybe this summer's World Championships in London, although that is not an IOC event. Maybe much later, if Cas' procedures drift on and on.

It is clearly preferable to those retests never having been done, and those cheats never being caught. But it is a flawed process, just as with the proposal to scratch all track and field world records recorded before 2005, clean athletes seemingly punished again for the crimes of those who defrauded them in the first place.

"It's a strange place to be," said Sayers. "It would be nice for legal processes to be sped up after someone is caught, because everyone needs to move on. There are going to be more and more athletes who've retired, picking up Olympic medals, thinking, 'If only…'

"It's getting on. Some of the kids I'm coaching don't even remember those Olympics.

"You very quickly feel like a has-been in sport. And I don't want to be one of those people talking about something that happened 20 years ago, and that being the best moment of their life."

Abakumova was something of an open secret in Beijing. Her physique had changed dramatically over the previous winter, and her distances followed suit: 61.43 metres at the Worlds in 2007, a jump to 70.78m in Beijing.

Sayers' British record of 65.75m was only 38 centimetres off the initial bronze. It would also have been good enough for silver at the two subsequent Olympics. It should have brought satisfaction.

"I remember having to compose myself afterwards and have a series of press interviews where I couldn't say that I'd just been cheated out of an Olympic medal," she said.

"Instead I had to say that it was a surprise that someone had improved five metres, and that the champion nearly had to break the world record to win.

"It's weird thinking about it now. We would all joke about Russian athletes, and some others, doping. We just had to accept that they were cheating.

"I had initially tried to remain naive about it, partly because I didn't feel at my own physical or mental peak. I thought, if they're doping they should be throwing further.

"When you feel you're not throwing as far as you could, you just get on with it. But when you feel like you really have, that's when it hits you: hang on, this really isn't right.

"I had a conversation with Kelly in the Olympic village in Beijing. I said, 'At least everyone was drug tested, so in a few years, who knows, we might be Olympic medallists.' Because it was just so obvious. So brutally obvious.

"It's great now that people can openly talk about it. Maybe we were all complicit, because we didn't talk about it in those interviews. But you had no concrete evidence, and so you had no way of policing your own sport. You just had to get on with it."

Sayers still loves athletics. She has started her own coaching and mentoring website, Javelin Champ, and will be Team GB's deputy chef de mission at the 2017 European Youth Olympic Festival.

Like so many in the sport, she finds herself holding two seemingly contradictory positions: defending what makes athletics so special, and acutely aware of where it has gone wrong.

And so the stark question that those many have had to ask themselves in retirement: had she known at the start of her career what she does now, would she still have committed to a life in athletics?

Sayers carried the Olympic torch through Lincolnshire in the run-up to London 2012, where she was hampered by an elbow injury

"Oh no, don't ask me that question! Um… it's really hard," she said.

"When I was first given a javelin to take home over the school Easter holidays I never thought, I'll make a living out of this, go to three Olympics, break the British record. I only thought, how far can I throw this?

"You become addicted to progress. As long as you keep improving, you keep going.

"I've beaten people who have been caught cheating. And there are always things you can improve. It just makes it a lot harder to beat them.

"The biggest problem with doping is that it pushes people who are clean into getting injured. That was my experience. I was guilty of pushing too hard in training, trying to make up the gap. I had seven operations in the eight years after Beijing.

"I would still do it. But I wouldn't want to know what I know now, because then I wouldn't have given everything to it. And I wouldn't want to be an athlete who didn't give everything to it. I did."

As Sayers prepares to say farewell to that competitive career, she displays little of the bitterness you might expect. She is honest about her own mistakes, hopeful about what might come next for athletics, open to being astonished by remarkable performances rather than cynical.

"You don't want people thinking everyone is cheating, because they honestly aren't," she added. "There aren't as many cheats as the cynics think there are. It's absolutely possible to make massive improvement in sport, because there are so many facets to it. Good coaching is the biggest performance-enhancer there is.

"But I do hope that announcing I've retired can be a line in the sand for me. I've wanted to do it for months, but I kept always thinking this legal process would be wrapped up, and I could look forward to a presentation."

She laughs. "On a positive, if the medal comes, I'll definitely do something. A retirement and medal party. Get together my family, my friends, my coaches, all my support team, and have a party.

"Everyone can dance round the medal, instead of their handbags. I'll probably have about 10 years to plan it, the way things are going, but still."

- Published13 September 2016

- Published2 May 2017

- Published2 May 2017

- Published28 June 2014

- Published3 March 2018