Panorama: Alberto Salazar's spectacular fall from grace

- Published

Alberto Salazar (centre) celebrates with Galen Rupp (left) and Mo Farah (right) at the London 2012 Olympics

Alberto Salazar wanted to win almost at any cost.

Once the most revered distance running coach in the world, his fall from grace has been spectacular.

Salazar helped Sir Mo Farah become Britain's most successful track athlete ever. Now he's appealing against a four-year ban from athletics and his beloved Nike Oregon Project has been closed down.

It all started to unravel for Salazar in 2015 when BBC Panorama and ProPublica exposed evidence of Salazar violating anti-doping rules, which eventually led to his ban from the sport.

But as I've been discovering, the story doesn't end there.

'That was the culture'

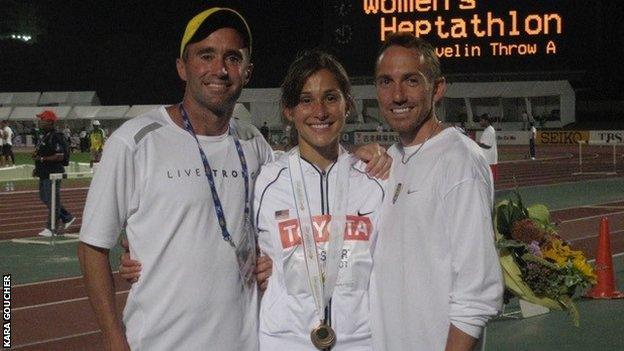

Alberto Salazar (left) used to coach Kara Goucher (centre) and Adam Goucher (right)

Kara and Adam Goucher joined the Oregon project in 2004. Kara, in particular, found success under Salazar, winning a silver medal in the 10,000m at the World Championships in 2007. But that success came at a price.

Both Kara and Adam spoke to me for Panorama in 2015, then became witnesses for the US Anti-Doping Agency (Usada) against the coach they once revered.

"It's taken a huge toll on me," said Kara. "Having to testify. We get the good news that he's found guilty, then there's still backlash and there's stuff - it's just never ending.

"I don't regret it, because the longer I stayed silent I was protecting their secrets and I was allowing it to continue."

Adam says he feels duped by Salazar: "I bought into his lies and I'm disappointed in myself for that. You know, I can look back and go, 'What the hell? Why didn't I just see through it?'"

As a marathon runner, Salazar was one of the most famous sportsmen in the US. His lifelong association with Nike was rewarded in 2001, when he was funded to create the world's most elite distance running programme, the Nike Oregon Project (NOP).

But some of his athletes now say he exercised complete control over them. Kara told Panorama: "He had total control of my life. Even to the point it was causing conflict between myself and my husband - whatever he asked me to do, I was going to do it."

Kara says her coach used sexually inappropriate language around her.

"Stuff that no coach should ever be saying. It's degrading. Specifically, for myself, after my son he was obsessed with the size of my breasts. And he would be talking about it openly in front of other people and making comments that were sexual in nature. It's just inappropriate."

Asked if anyone ever spoke up against him, she said: "No, because that was the culture. You do not stand up to Alberto. If you do, you're a negative person, you're out."

Salazar is now facing allegations of misconduct from a second organisation, the US Centre for SafeSport, which investigates claims of emotional, physical and sexual misconduct in sport.

He denies all allegations in relation to this.

Alarm bells

Ari Lambie left Nike Oregon Project after only 18 months

There was another NOP athlete that I'd always wanted to speak to. Ari Lambie had been a promising college runner who joined NOP in 2008. Tipped as a future Olympian, she lasted only 18 months at NOP, disappeared from running and had never spoken publicly about it. Until now.

She told Panorama that as soon as she arrived at NOP, alarms started ringing.

"I was regularly expressing concern that we were putting my body at risk. He would repeatedly tell me, 'You need to commit, you need to believe in this programme or I'm not going to coach you.'"

Elite athletes have their health closely scrutinised and women often use birth control pills to regulate periods - but Lambie says Salazar and Dr Jeffrey Brown, who treated Salazar's athletes, went too far.

She says Salazar and Dr Brown changed her contraceptive pill to try to increase her blood volume and boost performance, with little regard for her health.

"I was using one that would give me one period a month and they wanted me to try one that was one period every three months," she said.

Lambie said Salazar was overtraining her and, despite her warnings, she suffered from injury and fatigue. She said Salazar sent her to Dr Brown - to his office in Houston, Texas - where he put her on thyroid medication even though there was no medical need.

Thyroid medication isn't on the banned list although many anti-doping agencies, including the UK's, would like it to be, because some athletes and coaches have abused it believing it can help burn fat quicker and boost performance.

Sports endocrinologist Dr Nicky Keay told Panorama it was "conjecture" that thyroid drugs were a performance enhancer.

She said: "The consequences of giving extra thyroid hormone - to someone whose thyroid gland is working perfectly normally - [is] going to put it out if its optimal functioning range and put the person at risk of other health issues."

Lambie's thyroid levels were in the normal range, but she says she was "prescribed the full dose of thyroid [medication]".

"Within a few weeks I could feel jittery, I could feel my heart beating louder and faster, I was just uneasy - as tired or more tired than before. Mentally I was distraught. It just felt horrible.

"We were just throwing things at me and for a long time. Maybe I still do wonder if it was all those interventions that prevented me, my body, from actually recovering."

Adam Goucher also says he was prescribed thyroid drugs by Dr Brown, although this was before he joined the Oregon Project. He says he was on medication he didn't need for a decade and now worries about the impact on his health.

His career at NOP never really took off. "I never felt like myself again. It just never happened," he said. "My career ended a lot earlier than it should have, and I wish I could have that back."

Lambie also never fully recovered, but before Nike terminated her contract she says Salazar asked her to trial a supplement, to see if she would fail a drugs test.

"I was given a supplement to take, then gave Alberto urine that he could test to find out if it would, presumably, test positive on some result. But I don't know what the substance was.

"It confirms in my mind that Alberto was not acting in the spirit of the rules. He was always trying to get as close to breaking them as he could, for his advantage to his athletes, without getting caught."

In a statement, Salazar said: "The panel made clear that I simply had made 'unintentional mistakes that violated the rules, apparently motivated by my desire to provide the very best results and training for athletes under my care'.

"At no time did I give any supplement to any Oregon Project athlete for the purpose of determining whether that supplement would result in a positive test for a banned substance."

'Medicalisation of sport'

Travis Tygart runs Usada. He led the investigation into the since disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong.

After the Panorama/ProPublica investigation in 2015 he turned his attention to NOP, which he said is a prime example of the increasing "medicalisation of sport".

He said: "Whether it's birth control or thyroxine, sport has to deal with this medicalisation issue in a real way because athletes are being put in a situation where they really don't have much of a choice what medical care they have, because it's being directed by those who just want to win."

While giving an athlete prescription drugs they don't need in a bid to enhance performance might be unethical, it's not always against the rules. In pursuit of doping violations, Tygart says Nike tried to block him at every turn.

"Every time we turned around, another athlete was being represented by a Nike attorney and refused to cooperate with us," he said.

"The Nike castle brought up the drawbridge, they put alligators in the moat around it, sharpshooters on the tower, and they were going to do pretty much everything they legally felt they could do to avoid us getting to the truth.

"In this case in particular the BBC and Panorama, exposing parts of the truth, were really helpful."

A spokesman for Nike denied it had obstructed Usada's investigations.

They said: "The opposite is true. Nike has voluntarily cooperated with information requests from Usada, including turning over thousands of pages of documents to Usada. We welcome and respect the genuine efforts that are made to ensure that sport remains clean."

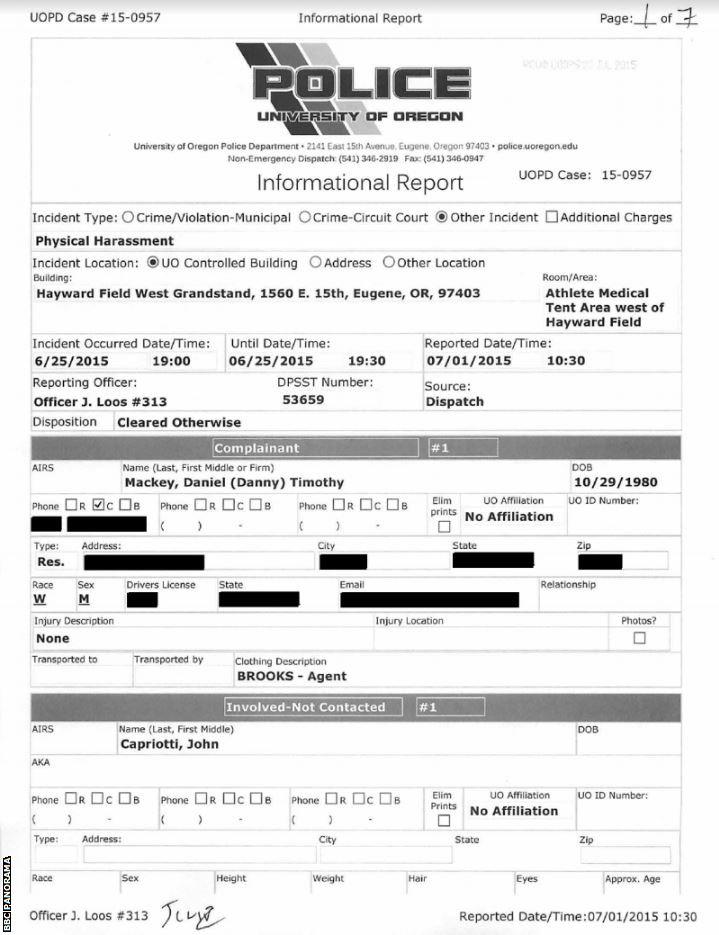

Danny Mackey used to work in the Nike laboratory in Oregon

One of those to help in exposing Salazar was Danny Mackey. Now a coach for Seattle-based Brooks Beasts running team, he used to work in the Nike laboratory within Nike's sprawling Beaverton campus in Oregon. He would do lab work for Salazar and his athletes.

He spoke to me anonymously in 2015, worried about the repercussions of speaking out. "I thought it'd be safer for me, safer for people that I work with."

Mackey says he was right to be scared.

A few weeks after the programme aired, he says he was at a US track meet when senior Nike executive John Capriotti aggressively confronted him.

"Up from behind me, I got grabbed by Capriotti."

Danny says Capriotti told him he knew he had been the anonymous whistleblower on the programme.

"He was swearing at me and telling me I was the blacked out face guy and that he'd kill me - I needed to keep my mouth shut."

Danny made a police complaint but decided not to take it further.

Capriotti told the BBC he "denied these allegations that were well publicised almost five years ago, and no charges were ever brought".

The first page of a complaint made by Danny Mackey to police against senior Nike executive John Capriotti

'I was the guinea pig'

Steve Magness used to be an assistant coach at Nike Oregon Project

In his apartment in Houston, Steve Magness reflects on a November afternoon in 2011, when he sat in his doctor's office with a needle in his arm for two hours. "I was the guinea pig," he said.

Magness, then an assistant coach at NOP, was being infused intravenously by Dr Brown with the legal supplement L-carnitine to see whether new research suggesting it could aid performance significantly was valid.

Magness said: "My understanding was that L-carnitine wasn't a banned substance. And I asked Dr Brown and Alberto, 'This is all legal?'

"They both said, 'Yeah. We're good.'"

He had reason to trust them. Dr Brown had been the Magness family endocrinologist for many years. And Salazar was his mentor, one of the world's most respected coaches.

"Alberto was super excited."

But some weeks later, Magness began to doubt if what he'd done had been within anti-doping rules. "There were a couple of emails. We were being told to not call it an infusion, so to just call it an injection if any athlete declared it."

Infusions or injections of legal substances were within the rules, so long as they didn't exceed 50ml every six hours. Steve had been given 10 times that amount. Inadvertently, he'd broken anti-doping rules.

Magness was never charged by Usada for this breach because he became the key witness for Usada in their investigation of Salazar and Dr Brown over their use of a prohibited infusion.

Two years later, in 2014, Farah would receive a series of injections of L-carnitine before the London Marathon, which Panorama has been investigating. UK Athletics and a lawyer for Farah have said the injections totalled 13.5ml, well within the legal limit.

Farah, declined to be interviewed by Panorama but gave an interview to The Times newspaper, in which he criticised whistle-blowers Magness (for breaking the infusion rules) and Kara Goucher (for using medication for her thyroid condition). He appeared to make no criticism of the coach who is now banned from the sport in disgrace.

Kara believes Farah's legacy is tainted as a result of his association with Salazar, as is her own. She said: "I think he should have left as soon as he found out [about the allegations against Salazar]."

Magness says the experience of being a whistle-blower was "traumatic" and hours of interviews, interrogations and court appearances have taken their toll. But he insists he doesn't regret it.

Magness and the Gouchers will have to go through it all over again in August, when Salazar and Dr Brown's appeal hearings begin at the Court of Arbitration for Sport (Cas).

Panorama contacted Dr Brown for comment but he did not respond.

The gamble

Salazar is fighting for his sporting life and says he looks forward to overturning the doping violations and his four-year ban. But it's a gamble.

Cas not only has the power to quash his convictions - it can also find new ones. Usada is seeking to prove additional charges and wants Salazar's ban from sport to be increased.

"We're seeking a lifetime ban. We think that's appropriate for the culture that was created as well as the specific anti-doping rule violations," said Tygart.

Farah has never failed a drugs test. There are no allegations he has cheated, yet his association with Salazar is once more under the spotlight.

By the time he returns to the track at this summer's Olympics in Tokyo, he will hope the long shadow cast by his former mentor has faded.

Additional reporting by Calum McKay and Kate McDonald.