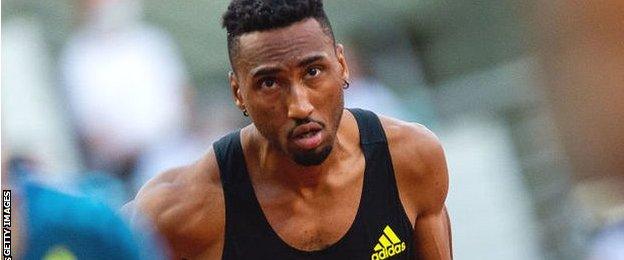

Matthew Hudson-Smith on teenage kicks, mid-career crises and Tokyo dreams

- Published

European 400m champion Hudson-Smith is seeking to regain the British title that he won four times in succession between 2016 and 2019

British Athletics Championships |

|---|

Dates: 25-27 June Venue: Manchester Regional Arena |

Coverage: Watch on British Athletics website and YouTube channel |

The route to glory sometimes sounds simple. It's steady, continuous improvement. Coaches gradually pouring potential into a medal-winning mould.

Round off the rough edges, iron out the technical kinks and slowly a contender morphs into a champion.

Matthew Hudson-Smith knows the reality is more complicated.

He was a prodigy. He won European 400m silver at 19. He was in an Olympic final at 21. All long limbs, raking stride and fathomless depths of stamina.

Give it a couple more years and Iwan Thomas' British record would be toast. A few more still and the world might be his. That was the assumption. That was the hope.

Yet, just a year after lining up in the final in Rio, he was ready to quit.

He had a new career vaguely sketched out, making use of his physical education and sports coaching degree. Something behind the scenes. A physio perhaps. A strength and conditioning expert.

But his mother knew best.

"She told me I had put in so much work, I have been doing it such a long time that I can't really go out like that," Hudson-Smith told BBC Sport.

"I realised I have to see it through.

Matthew Hudson-Smith - 400m | |

|---|---|

Personal best | 44.48 seconds (2016) |

2021 best | 45.51 |

Olympic qualifying standard | 44.90 |

"I don't want to be one of those athletes who looks back in their career and says they could have done more. I want to feel I have done everything in my power. That is what drives me.

"It is never plain sailing for anyone in sport. Everyone goes through it. You almost have to rediscover your passion and goals every day."

Hudson-Smith listened to his mother. And then left her. He decided if he was in, he was all in. He swapped his home city of Wolverhampton for Florida. The Black Country for the Sunshine State. A British training group for an international all-star one.

This season, his fourth in the United States, he has been alongside Olympic 400m champions Wayde van Niekerk and Shaunae Miller-Uibo and American sensation Noah Lyles.

But, while he's bulked out and grown up over the Atlantic, he still wants to keep some of that skinny kid who shocked himself and everyone else.

"When I was 19, everything came so easy, there was a bit of naivety and a bit of fun and that got me through," he said.

"You turn up and run and it is exciting, you get paid, you race people you see on TV, you're at major champs, you get your first senior call-up.

"I went from working a part-time job in the week to racing in the Diamond League at the weekend.

"It is stressful as you get older, it becomes less fun and more like a job. You have to remember what it is and keep some of that naivety."

That innocence stretches off the track. With athlete-media relations under more scrutiny than ever, Hudson-Smith meets the press without a playbook. He doesn't stick to pre-heated, pre-approved soundbites. And, despite some critics, it's the tactic that works for him.

"People definitely tried to make you more streamlined, professional and say all the right things, but that's just not me," he said.

"When they tried to put me in media training I just didn't want to do it.

"Honestly It makes the sport boring if people say the same thing, try and give the right answer every time.

"You don't want athletes to come and say the same thing. 'It was a good race, I tried to execute.' You want personalities, you want people to be happy, not robots.

"I say what is on the top of my head. And if you don't like it… you can't satisfy everybody. People are going to love you and hate you.

Hudson-Smith's four years in the United States has involved more strength work than ever before

"As long as I am being me, who cares? It's hard, it's stressful, you sacrifice so much, you are under so much pressure, there are always expectations, you have to keep an element of fun."

This week, Hudson-Smith will try to do just that.

He'll catch up with friends and family for the first time since the pandemic struck, watch some football, and then try to cement his spot in the British team for Tokyo at the trials in Manchester.

And he'll do it with some help from Britain's greatest 400m runner. Former world and Olympic champion Christine Ohuruogu is a friend, drops him regular texts of advice and encouragement.

"She told me it's all about the process," he said.

"If you have an in-depth look at the greatest British athletes - Dame Kelly Holmes, Dame Jessica Ennis-Hill, Chrissy - they have not had an easy sail.

"Everyone just remembers the success, not what they had to go through to get it.

"It all adds seasoning to the story. It just takes four years to change your life, honestly."

And, as Hudson-Smith explains, much longer to work out which bits are worth preserving as they are.

A Life in Ten Pictures: The iconic images that proved defining for John Lennon

Do you know your football anthems?: Take the quiz that will put your knowledge to the test