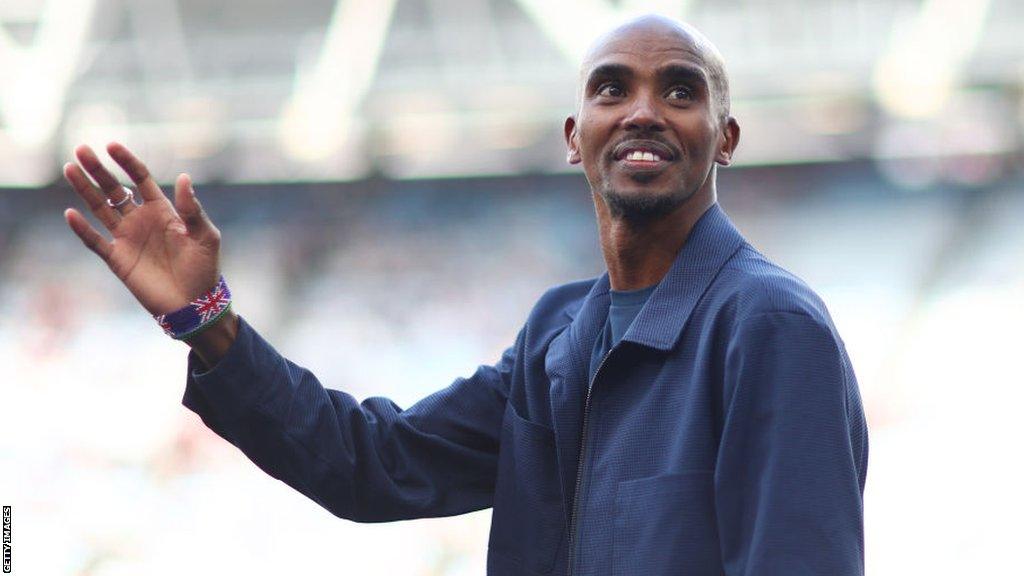

Mo Farah: British four-time Olympic champion set for final race of career at Great North Run

- Published

Mo Farah said the Great North Run would be the last race of his illustrious career after competing in this year's London Marathon

The expectant crowds cheer each closing metre. Mo Farah bares his teeth, alternating glances over either shoulder.

Then, the trademark kick to the finish.

The first of Farah's record six Great North Run victories, in which he held off Ethiopia's Mike Kigen in a close sprint finish, made him the first British winner of the race for 29 years in 2014.

That was a year which marked the mid-point of his defining moments; those unstoppable years between capturing double Olympic gold at both the London and Rio Games.

From the peak of his powers, to Farah's final farewell.

On Sunday, the 40-year-old will run the last race of his remarkable career in a fitting return to the North East to complete a goodbye tour which has also included final bows in London and Manchester this year.

Farah had long maintained that he would allow his body to dictate when he would bring the curtain down on his running career, one which delivered an unprecedented 10 successive global track distance titles.

Reluctantly, unable able to cope with the training demands required to compete at a level which could sustain his hunger for success, Farah announced earlier this year that time had finally come.

"I've had incredible support throughout the years at the Great North Run and I've always taken part from a young age, so it was a no-brainer really to make the decision to have my final race there," Farah tells BBC Sport.

"Finishing in the top three is my aim but I know, coming down to the finish line and knowing it is the last time, is going to be quite emotional in so many ways. Because, you know, this is it.

"The support this year has been incredible. To see how people engage with you, come up to you and have given their support and love, it's something that will always stay with me."

'Bye bye London!' - Farah reacts to final race in home city

The four-time Olympic champion will always be associated with his hair-raising triumphs inside an electric Olympic Stadium at London 2012.

There, in a cauldron of hysteria, a captivated crowd of 80,000 roared the Briton towards history.

Farah's 10,000m gold capped an unforgettable Super Saturday for the host nation, following fellow gold medal winners Jessica Ennis-Hill and Greg Rutherford in delivering another spectacular moment within an extraordinary hour, forever etched in the memories of all who witnessed it.

Seven days later, he became only the seventh man in Olympic history to add the 5,000m crown to that title at a single Games.

"The London Olympics stand out the most, and winning the 10,000m on Super Saturday," adds Farah.

"Honestly, that 45 minute-window was incredible. I still can't quite believe [I was a part of it]. I still just think 'wow'."

Farah's status as one of the all-time greats was cemented when he repeated that incredible double gold medal-winning feat four years later in Rio, even recovering from a fall to triumph in the 10,000m, before he finished on the track in 2017 by winning his 10th global gold at a home World Championships.

It is a list of accomplishments made all the more remarkable by the personal journey he has been on.

Farah seals second gold with 5,000m

Farah's successes, often accompanied by the infamous 'Mobot' celebration, rank among the greatest in the history of British athletics. It is under that spotlight which the public have come to know him far beyond his sporting exploits.

In a BBC documentary last year titled 'The Real Mo Farah', he revealed the other side to his story.

Rather than arriving as a refugee with his parents, as previously stated, a young Hussein Abdi Kahin was illegally brought to the UK from Djibouti at the age of nine.

Given a false name - Mohamed Farah - he was forced to look after another family's children.

School sport offered Farah an anchor, his PE teacher Alan Watkinson said. Farah has gone further; he believes running saved him.

"There are things you can't control in life, things you have no say in. There are challenges you have to face no matter who you are. Being trafficked here, that experience wasn't easy," Farah says.

"But I was lucky that someone believed in me, showed me something that would allow me to be myself. If it hadn't been for running, and being taken to my local club, it would have been a totally different story.

"You have to grab every opportunity with both hands and put in the work - that's the key."

It was a revelation that added to his already immense achievements, for which he was honoured for his services to athletics with a knighthood and voted BBC Sports Personality of the Year in 2017.

London Marathon 2023: Mo Farah finishes ninth to complete his final marathon

Six years on from making his competitive switch to the road, it has not quite proved the concluding chapter Farah hoped it might.

The six-time world track champion won the Chicago Marathon in a British record two hours 05:11 minutes in 2018. However his transition to the 26.2-mile race was otherwise blighted by injury struggles.

It led to a failed Olympic track return in 2021, while a surprise loss to club runner Ellis Cross over 10km in London last year further contributed to a fading aura of invincibility around an athlete who once dictated every race he contested.

"The marathon was hard. I'm glad I tried it, it was a good learning curve and I still broke the British record and European record at the time," Farah says.

"But, overall, I think the marathon probably wasn't for me in all honesty," he laughs.

There were also external frustrations, with Farah calling questions over his relationship with former coach Alberto Salazar - banned from the sport for four years in 2019 after being found guilty of doping violations - "depressing" and "unfair".

Farah was coached by Salazar at the Nike Oregon Project from 2011 until 2017, when the Briton left the programme.

He has never failed a drugs test or been accused of doping - and said at the time of Salazar's ban, which followed a four-year US Anti-Doping Agency investigation after claims first made in a BBC Panorama documentary, that he had "zero tolerance" for "anyone who breaks the rules or crosses a line".

Mo Farah completes his penultimate race as Eyob Faniel wins Great Manchester Run

The hip injury which kept Farah out of last year's autumn-held London Marathon was ultimately among the closing evidence required to lead his retirement decision.

And the reception he has received in his final outings from those who lined the streets of London and Manchester provided a touching reminder of the high regard in which he is held.

Determined not to allow a cold to ruin his goodbye in the capital last week, he placed fourth in The Big Half.

Now, at the very end of an illustrious career, one which has captured the imagination of a nation and inspired countless others, Farah's final 13.1 miles await him along the route from Newcastle to South Shields on Sunday.

"I am proud of what I've accomplished but at the same time I'm looking forward to being a parent and just a normal person," admits Farah.

"The hardest thing has been being away from my kids for so many years. Not being there for birthdays, missing out on moments at home knowing I have to be in a camp, I have to be at altitude. That was always tough.

"There's a sense of relief that is over, but that is what it took to win. That's what it took to become Olympic champion, world champion. It's just part of it. But it wasn't easy. Most people don't see all the hard work that goes into it.

"I'll still remain involved in the sport and I want to give back. But, right now, I want to take time off and be with my family."

The lives of three strangers with nothing in common collide: A deliciously dark tale, full of dupes, deceptions and delusions

What harm does vaping do to teenagers?: Panorama investigates the recent vaping phenomenon and its potential risks