'Take the next shot' - the new message from Kobe Bryant's final game

- Published

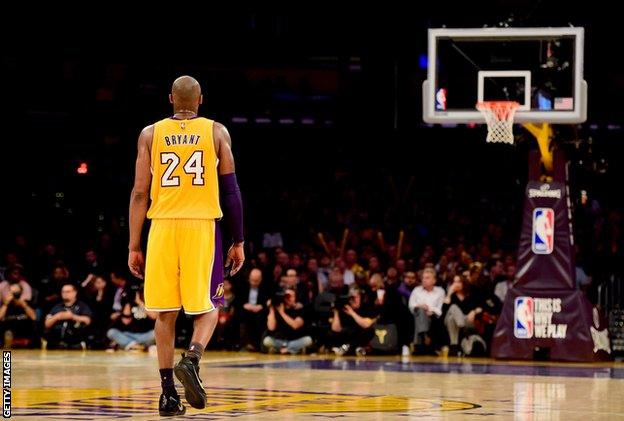

Kobe Bryant scored 60 points in his final NBA match for the Los Angeles Lakers

It is the last game of Kobe Bryant's career, on the final day of the 2016 NBA season, and his Los Angeles Lakers are down 10 with three minutes and change to go.

The result of this game has little meaning. His Lakers team, well past their prime, are not heading to the play-offs, and neither are their opponents, the Utah Jazz. The NBA story of the day is north of LA in Oakland, where the Golden State Warriors are about to become the most successful regular season team in NBA history. This is Kobe's final game, but the action is elsewhere, and he is going to lose.

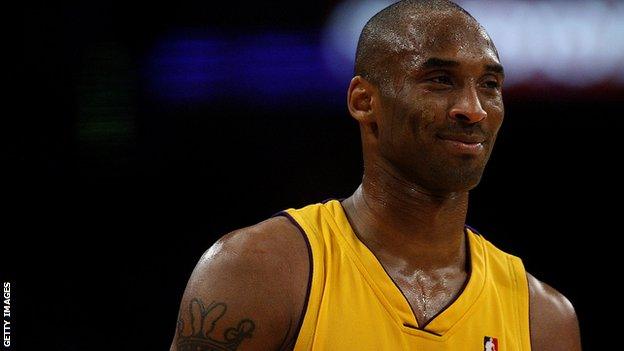

The Lakers were the worst team in the Western Conference that year, having finished second-last the year before. Kobe, then 37, was a titan of the game - a winner of five championships - but he had hobbled towards retirement, overpaid and underproductive, barking at young and inadequate team-mates all year. Two years earlier, an Achilles injury had robbed him of his powers, closing the window on 15 years of greatness after he had, in 1998, become the youngest All-Star in league history. He was 19.

Three minutes 11 seconds remain in the game. Kobe has the ball on the left block, his back to the basket. He surveys the NBA floor, as he has done 1,565 times before. Only two men have scored more points than him. He is built no differently than the average NBA player - 6ft 6in, strong, athletic - yet he has eclipsed almost all of them, not least his idol Michael Jordan, who is one place behind him on the all-time list. Kobe spins, drives and hops to the basket, evading two defenders. Lay-up. Eight-point game.

I fell in love with the game of basketball at 13. When I visited my grandparents soon after, in the hoopless hillside gloom of the Welsh countryside, I dribbled a ball every day until dark, down flat, empty roads. I have since spent more time playing basketball - usually alone on a hoop - than I have doing just about anything else. I have spun, driven and hopped to the basket, and evaded the countless defenders in my mind. I have come back from impossible deficits and drained the game-winning shot. And I have walked off an empty court, as alone in that knowledge as any daydreaming kid.

Two minutes 23 seconds to go. After a Utah bucket, the Lakers' deficit is back to 10. Kobe, on the left wing but now facing his defender, dribbles from side to side. He makes for the middle of the floor, then spins and dives to the hoop, drawing a foul. He heads to the line, making both free-throws to muffled chants of "MVP". Eight-point game.

This video has been removed for rights reasons

I was one of hundreds of millions of new NBA fans in the 2000s. The game is now global, second in popularity only to football. More than anyone, Kobe was the face of that revolution. Jordan came first and LeBron James has followed, but Kobe was the first truly global icon. Jordan and LeBron were better, but Kobe was, for many, the image of the NBA. Every current NBA player grew up watching him. LeBron, who was 13 when Kobe made his first All-Star game, revered him, while the superstars of today - my generation - discovered him at his peak. "I started playing ball because of Kobe after watching the 2010 finals," wrote Joel Embiid - the Cameroonian star of Kobe's hometown team, Philadelphia - after his death at the age of 41. "I had never watched ball before that and that finals was the turning point of my life."

With one minute 49 seconds to go, Kobe pushes the ball down the floor. He slips past his team-mate's screen and ploughs through the defender up ahead, avoiding the reaching hand of another. Two giant steps and he is at the cup. He flicks the ball high off the glass. It drops in. Six-point game. The crowd roars. The broadcast cuts to his wife and two of his daughters - smiling, clapping, basking in the moment.

I did not love Kobe growing up. I loved AI - Allen Iverson. He was an equally complex and generational athlete; a 6ft maestro in a game of giants, whose will to win defied gravity, and was only matched by Kobe. AI never reached Kobe's heights - which made Kobe an enemy, not a hero. In one of Iverson's final moments of brilliance in 2010, it was Kobe who put an end to his run, just as he had in the 2001 NBA Finals - Iverson's only shot at the title. In all sports, only a handful of opponents are ever worthy of your hate. When they die, you realise the hate was love.

The camera is back on Kobe - bent double, grimacing, striving for air. It is Lakers ball, down six. Kobe nods, his team-mate inbounds, and with 94 seconds left in his career, he dribbles up court.

As a boy, the first headline I remember seeing on ESPN was the collapse of the rape case against Bryant in 2004., external I knew nothing about the league or its stars. This was my introduction. The story disappeared, and I was too young to chase it. I never did, not wanting to find a reality that would scar the game. Never, that is, until Kobe's death. Last week I read of the 19-year-old hotel employee who accused Bryant, then 24, of raping her. At first Kobe denied having sex with her. Then he relented but maintained it was consensual. She was bruised. He claimed it was part of games he played. "My hands are strong. I don't know," he said. The case was settled. Bryant apologised, without admitting guilt. How does this change everything? I do not yet know.

Kobe calls for a high screen from a team-mate. Two Jazz defenders swarm. In the split-second before they reach him, Kobe throws the ball ahead and dives into the gap between them. He stops on a dime, pulls up. The net snaps back in perfection. The crowd erupts. Jay-Z, Jack Nicholson, Kendrick Lamar, David Beckham, Kanye West. The world is here. Four-point game.

Bryant played his entire 20-year career with the Los Angeles Lakers

Barack Obama has written that basketball taught him "an attitude that didn't just have to do with the sport". Respect, the future US president wrote in Dreams Of My Father, "came from what you did and not who your daddy was". It was on the court that Obama, the stoic of the Oval Office, learned that you "didn't let anyone sneak up behind you to see emotions… you didn't want them to see".

Kobe is calm. Whatever he is feeling is hidden to the 20,000 fans now on their feet and the five Utah Jazz players in front of him. With 64 seconds left as a basketball player, he takes a screen and drifts to the left arc. He head-fakes his defender to get a step on him, but the guy is right there. Then he rises, out of nothing, falling away, one foot an inch beyond the three-point line, the other almost out of bounds. He rises, the defender rising with him at full stretch. He has no business making this shot. Even the best shooters miss more than half the time - and from out here Kobe is not one of the best, he is barely even average. But this shot is not average, it is hard. It is the shot you do not think he can make - the one he should not take - and that makes it the one he is going to make. "Bryant… on its way… it's a one-point game!"

The world, wrote VS Naipaul, is a cold place. Those who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it. But Kobe was colder than the world. He was, I told myself as I played, ice cold. Growing up in the internet era, which Kobe's career mirrored and helped shape, it became my username: icecold13. "Don't let up, don't cruise, don't give them hope," I told myself whenever I was up. "Be Kobe. Be merciless. Win." With the game on the line, I knew where I was going: to the right block - to spin, kick, rise, snap, and fade from 15 feet. To ice the game, just like Kobe.

Thirty-six seconds left, down one. This is it. Every second of the past two and a half minutes - of the past 20 years - has been for this. Down one, what have you got? The arena is in meltdown. Everyone in the building knows Kobe is pulling up, but from where? He hovers at half court, calculating. The screen comes, inviting Kobe left. He takes three steps, just enough to make his defender chase - and then dives back to the right, shaking his man. He pushes the ball ahead and begins to shape towards the basket. That is it, he has already decided. He is 28 feet away, way out of range - but the second defender is a few feet back; he is going to live or die from here. He takes one sharp, left-hand dribble, gets to 22 feet, stops on a pin and pulls up.

He hangs in the air, two feet off the ground. His whole body is in perfect alignment with the hoop, his elbow at right angles. He could be suspended by an invisible thread. All that is left is for him to let it fly. "Bryant... for the lead!" Bang. As the ball snaps through the net, Kobe has already landed - his balance in tact, his arm outstretched, his entire being oblivious to the roar of the 20,000 surrounding him. It is the perfect shot. Lakers by one. For the first time, Kobe's ice mask breaks. He thuds his chest. It is over.

Watch: When Bryant scored 60 points in his final LA Lakers game

In the hours after Bryant's death, one famed coach spoke, between tears, of "looking at my young players and seeing how emotional they are", despite the fact "they didn't even know him". But we all knew him. No-one - in LA or anywhere else - stepped on to a basketball court without soon hearing Kobe's name. After his death, we went online. "This will never seem real," wrote one NBA player. "I need to get off Twitter but I can't close it," a friend texted me two hours after the news broke. In a tweet liked 244,000 times, someone wrote: "Kobe probably in heaven looking down at us like: 'You over there crying and you need to be in the gym putting in work.'" We went online. And then we went to a gym, a court, a hoop - and put in work. Spin, kick, rise, snap, fade. Spin, kick, rise, snap, fade. Spin, kick, rise, snap, fade.

With nothing left, Kobe Bean Bryant put up 15 straight points. Left, right, lay-up, pull-up, two, three - whatever it took. In his final act, he left his message. You can miss, trail, lose, fail - but take the next shot. And the shot after that. Kobe kept shooting that night, as he always did. With three minutes left, he had shot 45 times - an unprecedented number. The Lakers were down 10. He had failed - the fighter who did not know how to quit. And then he took one more shot, and the one after that. He kept shooting, until the buzzer sounded and he had won. He won that final night in 2016. In death, he is in the minds of a billion people. Long after grief, he will live. He is dead. He is more alive than ever.

Harry Lambert, external is special correspondent at the New Statesman.