Dealing with depression - boxing's ongoing fight

- Published

There is no hiding behind team-mates in boxing. There is no reward for those only willing to put in half a shift. And often when the lights go out and that adrenaline rush subsides, a boxer's feeling of solitude is only magnified.

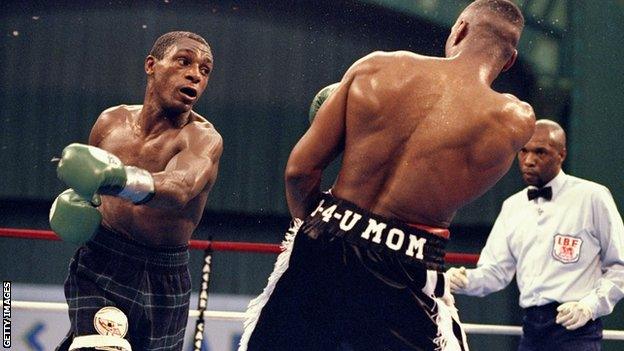

Herol Graham, external is arguably the best British boxer never to have won a world title. A British and European champion at light-middleweight and middleweight, Graham won 48 of his 54 pro bouts but lost three world title challenges.

In 1989 Graham was narrowly outpointed by Jamaican great Mike McCallum. The following year Graham fought Julian Jackson, one of the biggest punchers in history, for the WBC middleweight crown. Having dominated the first four rounds and been on the verge of stopping the Virgin Islander, Graham left his chin exposed and was rendered unconscious before he hit the canvas.

Graham retired in 1992, only to return four years later and earn a third world title shot in 1998, this time against the American Charles Brewer.

The challenger dropped Brewer twice before the champion rallied and stopped Graham in the 10th round. Graham's rare and mercurial talent was never fully fulfilled. But it was when he hung up the gloves for good that his problems really began.

"I was driving and I stopped and bought some brandy," says the 54-year-old Graham, who now lives with his partner Karen in London.

"I was crying, thinking about my mother and father, brothers and sisters. I wanted to end my life. I cut my left wrist but woke up in the morning and thought: 'I'm still here'. So I toddled off to the hospital and they looked at me and said: 'How you going Bomber?!' They fixed me up and sent me away."

It took Graham a long time to get the support he needed. "I met up with Herol again about five years ago," says Graham's partner Karen, his childhood sweetheart.

"I drove up to Sheffield and within about five minutes I could see things were pretty bad. Emotionally, financially and spiritually, he was quite broken. It became apparent that the only way to get him the help he needed was to get him sectioned. I called the police and they picked him up."

"I thought I was a nutter at first," says Graham. "But it's for your own security, to prevent you harming yourself. And it did help, I got myself back together."

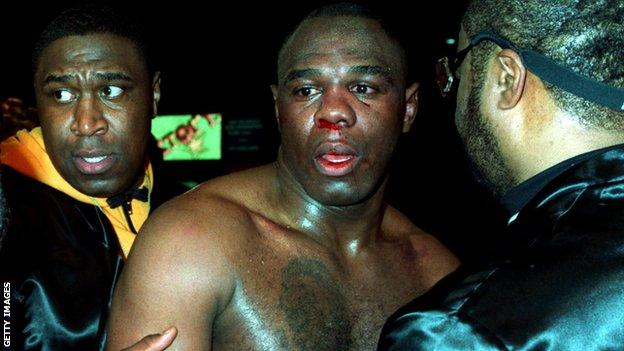

Sadly, Graham's story is not uncommon. Michael Bentt, external won the WBO heavyweight crown from Tommy Morrison in 1993 but lost his title to Britain's Herbie Hide only five months later, a defeat that took a devastating toll.

"I remember putting a gun to my head because I was lonely," says Bentt, who was one of the most decorated amateurs in American history.

"I didn't want to be around people, because people wanted to hear about my last fight and how I got knocked out. I was suicidal, I was depressed and I was drinking. I'd get in my car and drive on the highway at night, close my eyes and count to 30 and see what happened. Luckily I never crashed."

How could two seemingly powerful men be reduced to such emotional rubble? In truth, both Graham and Bentt entered the ring already bearing severe mental scarring, scarring invisible to just about everyone else.

"From the age of eight I was subjected to sexual abuse," says Graham. "I kept it (secret) for over 15 years. Boxing was my defence. I'm not a violent person but if anyone touched me in boxing, I'd smash them."

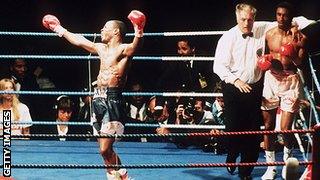

Chris Eubank beating Michael Watson in 1991.

"I blame my upbringing," says Bentt, who was born in London but raised in New York. "Even before I started boxing I had suicidal thoughts. When you see your father do things to your mum, it's confusing. You start to question your self-worth. I have always been depressed. It's not because of boxing. It's an element, what with the neurological damage, but only an element.

"We have to go even further beyond the act of boxing and figure out why this person is depressed to begin with and why this person is willing to get hit in the head in the first place."

Peter Hamlyn is a consultant neurosurgeon at the Institute of Sports Exercise and Health at University College London and the man who saved the life of Michael Watson following his defeat by Chris Eubank in 1991.

"You can see standard dementia process produced by repeated trauma to the head and as part of the dementia spectrum there are mood swings and depression," says Mr Hamlyn.

"It's always difficult in an individual case to say depression or dementia is due to repeated blows sustained, be they boxers, jockeys, rugby players or American footballers, or whether it is an ordinary case of Parkinson's or depression.

Hamlyn is hopeful that more research into the issue will garner important results. "One exciting line of study is the genetics of brain injury, and how different individuals respond to the same trauma," says Mr Hamlyn.

"There are a lot of boxers who had long careers and took repeated blows and came out unscathed, while others developed punch-drunk syndrome.

"Different brains behave in different ways and the genetics of that we are beginning to unpick. That's going to deliver us a situation where we'll be able tell certain individuals it's unwise to pursue this type of sport, pick another one"

In the meantime could more be done to protect those who might be vulnerable? Dr Margaret Goodman is a neurologist and former ringside physician. She feels that much more should be done to protect fighters from potential damage.

"Depression is quite prevalent among boxers," says Dr Goodman. "It is almost never diagnosed until it's too late and it manifests itself in so many negative ways.

"A strong number of patients with concussion have depression symptoms, but in boxing concussion is very badly diagnosed - as is depression - so I think the two go hand in hand in the sport."

After losing his title to Herbie Hide, Michael Bentt tried to commit suicide.

So what of the authorities that govern the sport? Boxing governance is fragmented, with each country having its own body which administers the sport. Robert Smith is the general secretary of the British Boxing Board of Control.

"Everyone involved in the sport knows the dangers of the sport," says Smith. "The Board of Control has medical provisions to make it as safe as possible. Every single boxer in the UK is scanned by an MRI every year, we monitor those scans and if there is any deterioration they are stopped from boxing.

"We don't do anything on the mental health side of it. It's a difficult field, I'm not qualified to do that. We have drug testing and if anybody is found taking anti-depressants we'd have to look into it seriously.

"They [anti-depressants] are on the banned list, a fit young person shouldn't need anything like that."

Bentt believes boxing is essentially a selfish sport and that "the onus in on the fighter to be prepared" adding: "It's the inherent nature of boxing to only be concerned with a person who can do something for you in that moment."

Dr Caroline Silby is a psychologist who has worked extensively with boxers and believes governing bodies need to do more to understand and develop the idea that "a boxer's mental health is as important as their physical health".

Dr Silby says by the time the more obvious signs of depression have been identified it's often too late. "Prevention needs to include awareness and education," she explained. "There should be informal assessments that athletes and trainers can use on a daily basis, related mood and sleep and eating patterns.

"On the treatment side national bodies need to have set tracks [standard procedures] on treatment, on diagnosis, because when athletes come forward you don't have a lot of time to look around and to get help."

Dr. Silby is also critical of the lack of support in place for those who face the difficult challenge of leaving sport behind.

"We absolutely need to do a better job on 'post sport transitional support'," she continued. "Once athletes leave the sport our job doesn't end, we need to continue to provide support to move through that very difficult transition."

There are also other factors to consider in addition to a boxer's mental health background and their potential disposition to brain injury and their consequences. Boxing, and sport in general can create powerful psychological elements that shape an athlete's thinking.

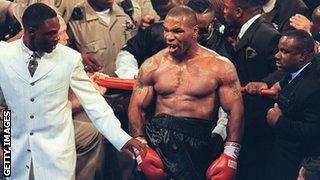

Mike Tyson was disqualified at the end of the third round of his fight with WBA heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield in June 1997.

"Boxers compete in a sport where the definition of success includes a win at all cost attitude," says Dr Silby. "All of your value as a person is tied to your athletic achievements and that leaves these athletes vulnerable to depression.

"We should be trying to reposition that definition of success to develop healthy individuals whose athletic outcome matches their capabilities. The attention to the person first and athlete second is a critical first step in mitigating and preventing this illness.

"This win at all cost thinking extends beyond the athlete; it is imbued in them form everyone they come in contact with and it has a damming effect

"There's a network that surrounds a fighter that doesn't really accept a loss, telling them they didn't really lose, that the judges were bad, the referee was bad, all to shield them from the reality of what's going on in their career."

It seems so many desperate aspects can combine to cause some fighters to suffer grievously at the hands of the black dog of depression. Will anything ever change?

Could a boxers' union that looks out for the interests of all fighters help? It's unlikely according to Bentt.

"There's never going to be one because that infringes on potential earning," said the American.

"Insure boxing? That gets very expensive. It's not in the promoter's interest. So what if a boxer lapses into a four day coma, because the public will always lust for blood and they know that.

"This problem will never get solved unless people decide not to box."

You can listen again to 'Fight For Life' or download the Sportshour Podcast. Sportshour is on the BBC World Service every Saturday at 10:00 GMT.

- Published3 January 2014

- Published16 January 2014

- Published30 December 2013