Carl Froch v George Groves: Rivalry a welcome throwback

- Published

Rivalries are the lifeblood of any sport and the rematch between Carl Froch and George Groves will reach the furthest veins and capillaries of British boxing. Pumping out to parts other fights cannot reach, rather than circulating the core.

Aficionados are wont to complain when their beloved sport, whatever that sport may be, opens its doors to outsiders. The uninitiated, the ill-informed, the glory-hunters.

But Barry Hearn, who promoted some of the biggest fights in British boxing history, knows the value of rivalries - and their ability to unite and divide a nation, rather than a small circle of devotees - better than most.

"The purists of any sport are small in number," says Hearn, who promoted the two classic encounters between Nigel Benn and Chris Eubank in the early 1990s, the second of which drew a television audience of 16.5m, as well as both fights between Eubank and Michael Watson.

"The volume comes from working people who want to be entertained. It's not just about pleasing the Blazer Brigade, it's about knowing your target market."

The failure of British boxing to engage with the wider public over the past two decades is attributable to a number of reasons.

The sport's switch from terrestrial to satellite television in the mid-1990s decimated its viewership virtually overnight. In turn, the print media was less inclined to cover fights involving fighters without television exposure.

There have been British boxers who have become superstars in the post-terrestrial age. An estimated 10,000 fans followed Ricky Hatton to Las Vegas in 2007 to see him get knocked out by Floyd Mayweather;, external Joe Calzaghe drew 50,000 to his fight against Mikkel Kessler, external at Cardiff's Millennium Stadium in 2007.

But it took Calzaghe a long time to reach such heights, which arguably had as much to do with a lack of domestic rivals as a lack of exposure or personality on his part.

"Joe might be the best British fighter there's ever been," says Hatton. "Unfortunately, he didn't have a peak Chris Eubank [whom Calzaghe beat in 1997] or Nigel Benn in his era. Every boxer sits around hoping they get a domestic rival. Benn and Eubank made each other."

Stoppage was unjust - Groves

In other words Hearn, as well as being a visionary promoter, was lucky: to have one world-class fighter in a given weight class at any one time is a bonus; to have Benn, Eubank, Watson and Irishman Steve Collins enter the stage at the same time was bordering on the miraculous.

Boxing's biggest stars rarely align when shining brightest, and Calzaghe slipped into retirement just as Froch was beginning to get his due.

Instead, Froch had to take a harder road to mainstream recognition, engaging in a succession of gruelling world title encounters - some of them far from home - culminating in his controversial ninth-round stoppage of Groves last November.

Most expected Froch-Groves I to be a mismatch. Instead, Groves gave his more experienced rival fits, flooring him in the first round. The 25-year-old was ahead on all three judges' scorecards when referee Howard Foster called a halt to proceedings in the ninth, prematurely in the opinion of most observers.

It is Groves's sense of righteous indignation - and Froch's irritation at the suggestion the challenger for his WBA and IBF super-middleweight titles was robbed - that makes their rematch more redolent of the second bout between Eubank and Watson, external than the second between Eubank and Benn.

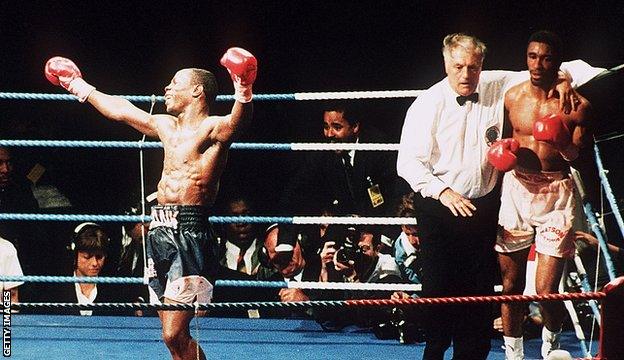

Chris Eubank's rematch with Michael Watson in 1991 left the latter with life-threatening injuries

There was no controversy surrounding Eubank's ninth-round stoppage of Benn in 1990,, external which is partly why it took them three years to get it on again. In addition, Eubank was only 24 when that first fight took place, Benn 26. As such, Hearn realised they had time on their side - to build their respective profiles, build the suspense, allow the value of a return fight to appreciate.

In contrast, the consensus was that Watson was robbed of the decision when challenging for Eubank's WBO middleweight crown in 1991.

Watson lodged a protest with the WBO, just as Groves lobbied the IBF, and a rematch was ordered. The build-up to the return bout was even more vitriolic than first time round, with Watson's sense of righteousness stoked by a mischievous media and a public high on a sense of vicarious victimhood.

At the news conference to formally announce the rematch, Eubank turned to Watson and said: "You make me sick, you're pitiful. You lost the fight and you're still whingeing like a child." Eubank promptly got up and walked out. In the following few months, their relationship went rapidly downhill.

The 36-year-old Froch, who does not have time on his side, has spent the past three months calling Groves "a whinger". Meanwhile, Groves, just as Watson did, has laid claim to the title of "People's Champion".

When they finally meet again on 31 May - in a football stadium, just like Eubank and Watson second time around - they will be sick of the sight and the sound of each other.

Hopefully, the similarities end there: the return bout between Eubank and Watson left the latter with life-threatening injuries from which he never fully recovered.

Mercifully, rematches in boxing are rarely as savage as the original. Having tasted each other's fury, combatants are usually more wary when they meet again. Although try telling that to Froch, whose return bout against Kessler last May, external was better than the original and as thrilling as his first bout with Groves.

The build-up to Froch-Groves II will be all about the beef and the showbiz, the flim-flam, the absurdity and the nonsense. Promoter Eddie Hearn, son of Barry, has learned well. As a result, millions from across Britain will tune in on fight night. At which point reality will kick in.

With both men striving to authenticate their greatness against their biggest rival on the biggest stage, the hope is they will also authenticate the greatness of the sport they compete in. Which, for boxing, can only be a good thing.

- Published13 February 2014

- Published5 February 2014

- Published24 November 2013

- Published24 November 2013