Nick Blackwell: How boxing's inherent darkness also makes it attractive

- Published

- comments

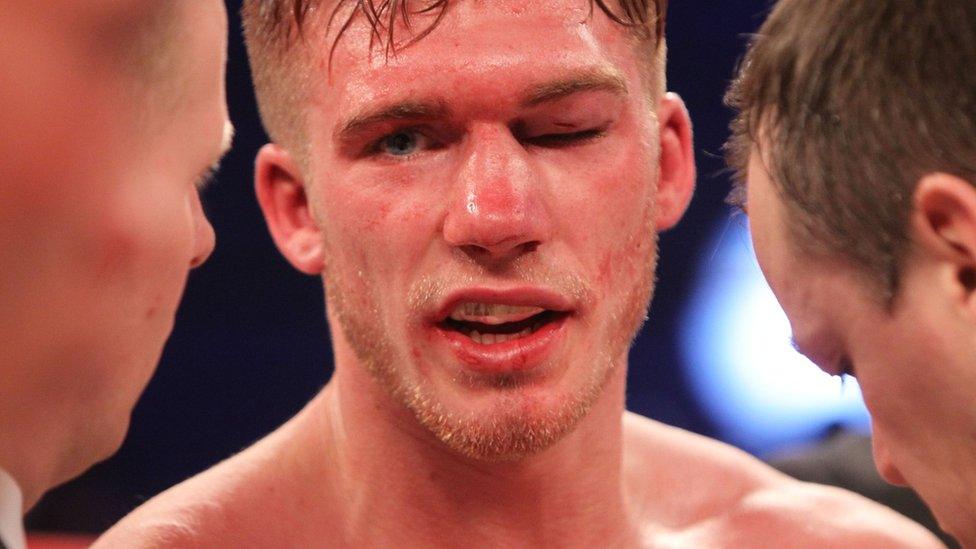

Nick Blackwell was stopped in the 10th round against Chris Eubank Jr

When boxing is at its most compelling, it is also at its most dangerous. It is one of the sport's many uncomfortable truths, as Nick Blackwell will attest to.

It is a relief that he can attest to anything. When he was sent into a coma by a combination of Chris Eubank Jr's fists and an anaesthetist's needle, things looked bleak. But after a seven-day sleep, Blackwell has a future.

As he contemplates life without boxing from his hospital bed, one wonders whether the knowledge he was injured while providing such stirring entertainment will be of any comfort. More likely, he just wants to fight again.

Many who have been watching boxing for long enough will have felt deep ambivalence towards the sport prior to seeing Blackwell leave the ring on a stretcher. It is possible, even natural, to love boxing and have huge respect for its practitioners while understanding why others wish to consign it to history.

When the American sportswriter AJ Liebling referred to boxing as "the sweet science", I can only assume he was being ironic. Even the two 'Sugars', Ray Robinson and Ray Leonard, had more in common with devastation than sweetness.

Boxer Nick Blackwell woke from his induced coma on Saturday

It is boxing's inherent darkness that has made it so attractive to generations of writers, artists and filmmakers. Like bats to a cave. Anyone who is fascinated by and gains pleasure from boxing and boxers contains a streak of voyeurism.

Most boxers punch for peanuts - someone ranked in the top 10 in his division in Britain might be on less than the minimum wage - and go about their business in boxing's dark alleys, waiting to get their throat cut. They are little more than pieces in some grotesque, real-life board game, in which there are many more snakes than ladders.

Even many successful boxers, those who win belts and inspire column inches, have a relationship with the sport that is strained and twisted.

American legend Bernard Hopkins once told me: "If any of your kids or grandkids want to box, distract and discourage them early. In fact, I would tell my worst enemy's kids not to box. I don't believe that any part of the body was made to be hit."

Boxing offered Hopkins a way out of prison. And so you might argue that the fighter, a serial criminal and convicted armed robber, had no choice. But why was he still boxing when he was almost 50 and had financial security?

'Boxers enjoy punching people and getting hit'

'Nobody to blame' for Blackwell injury

One answer is that boxers are special people, almost impenetrable to outsiders. Another answer is that boxers fight because of a deep compulsion. As difficult as it is for people to understand, boxers enjoy punching people and getting hit.

The argument that boxing exploits the poor is questionable in the 21st Century. You'll struggle to find a more polite, intelligent bunch of kids than Great Britain's amateurs in Sheffield. The notion that because they are from working-class backgrounds they were doomed to fight is deeply patronising.

But that old cliche about boxing saving people is also a truism. For some kids brought up in straitened circumstances or on the wrong side of the tracks, boxing is one of the few ways to achieve respectability. And if boxing isn't respectable enough for you, maybe write to the Government and ask for more tennis courts, swimming pools and velodromes to be built in our inner-cities.

'Owen paid for his love with his life'

A statue of Johnny Owen stands inside the main shopping centre in Merthyr Tydfil

Hugh McIlvanney, the doyen of British boxing writing who retired a couple of weeks before Blackwell sustained his injury, perhaps put it best. On Welsh boxer Johnny Owen, who died seven weeks after a fight against Lupe Pintor in 1980, the Scot wrote: "His tragedy was to find himself articulate in such a dangerous language."

Owen was a nice, quiet kid who could roar in the ring. Just like Blackwell. Owen paid for his love with his life, Blackwell was luckier. Whether Blackwell will conclude that the roars of his brief career were worth the savage ending remains to be seen. But boxers who sustain serious injuries in the ring tend to be more philosophical about the sport's risks than those who wish to abolish it.

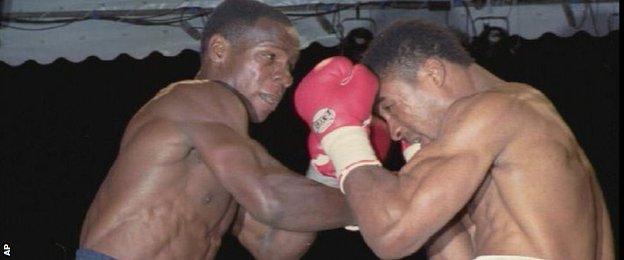

A few years ago, I spent a long afternoon talking boxing with Michael Watson in a north London cafe. In 1991, Watson was punched into a coma by Chris Eubank Sr, a brutal full stop to a brutal fight at White Hart Lane. Watson teetered on the brink of death for months before staging the most incredible comeback. But the comeback only went so far and he was never the same again.

Watson bore no bitterness towards boxing and was proud that the medical improvements put in place following his darkest night had helped saved the lives of boxers who came after him. You can maybe add Blackwell to that list.

But one line Watson came out with chilled the bones. Asked to explain the continuing appeal of boxing in a supposedly civilised age, he replied: "It's what people love to see. It's human nature. No different to seeing dogs fight."

Chris Eubank Sr put Michael Watson in a coma

A defender of boxing might point out that dogs don't have a choice. But the mere fact that dog fighting has been outlawed in Britain since 1835 while people still pack out arenas to watch men and women box is food for thought.

But you only have to watch the news to know this civilised age is not as civilised as you might think. And, anyway, how civilised is restricting a man's choice? After Sonny Liston beat Floyd Patterson for a second time within a round in 1963, reporters asked the world heavyweight champion if he thought Patterson should retire. Liston replied: "Would you tell a bird he can't fly?"

Watson still loved boxing enough to be ringside when Nigel Benn fought Gerald McClellan in 1995. That night, McClellan suffered permanent brain damage and was also left blind, confined to a wheelchair and requiring round-the-clock care.

While journalists struggled to make sense of what they had witnessed, Benn was unequivocal: "You got what you wanted to see."

And Benn was probably right. The fight was boxing at its most compelling and everything most fans wanted. Except for the part where his opponent nearly died. And that is the uncomfortable truth that boxing's fans and chroniclers must live with.

- Published4 April 2016

- Published31 March 2016

- Attribution

- Published28 March 2016