Sonny Liston: The mysterious death that haunts boxing

- Published

- comments

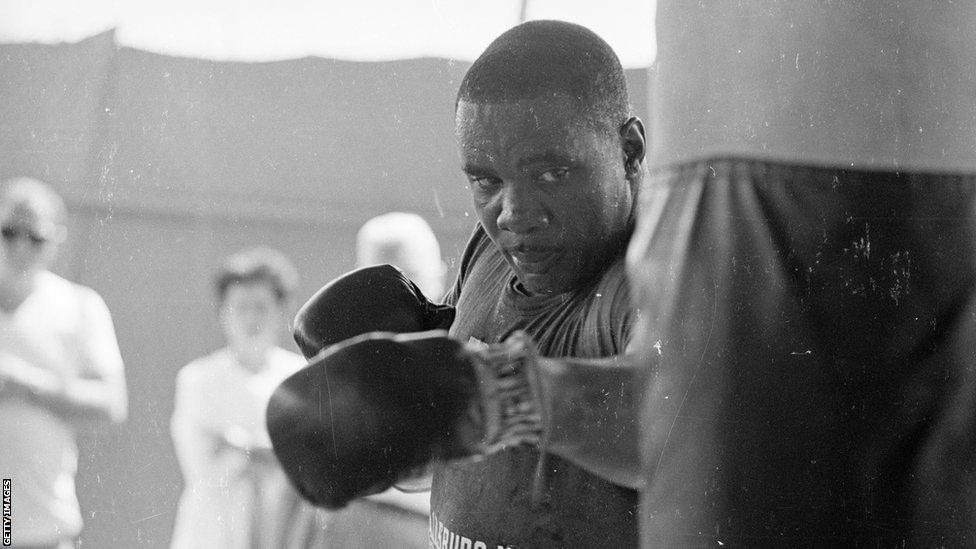

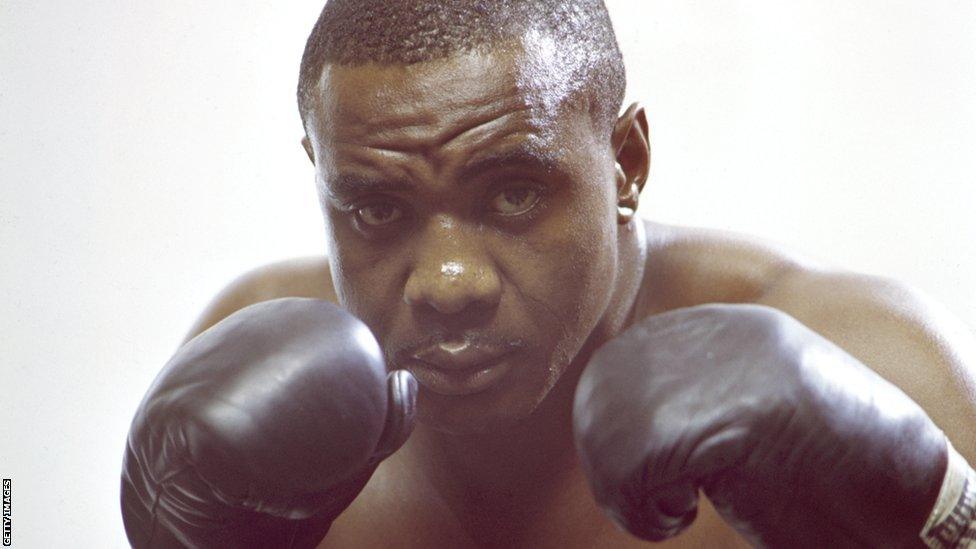

Sonny Liston became world heavyweight champion in 1962 and fought Muhammad Ali twice

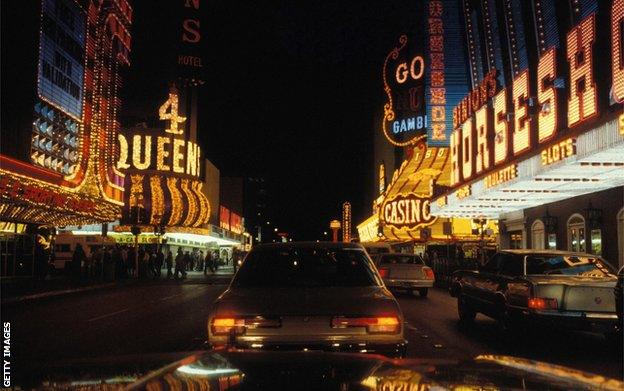

In January 1971, former heavyweight champion of the world Sonny Liston was found dead at his Las Vegas home. A coroner ruled that he died of natural causes - but some say the truth is far darker.

It was late in the evening when Geraldine Liston returned home and found the newspapers piled up at her door.

She had been trying to contact her husband - the heavyweight boxer Sonny Liston - for almost two weeks but had failed to get through to him. When her most recent call went unanswered, she apologised to her mother, who she had been visiting in St Louis over Christmas, and rushed back to Las Vegas to check on him.

The doors were unlocked and the house was in darkness. Geraldine felt uneasy. She hoped to find her husband in one of his usual spots - perhaps playing cards with a friend or watching TV. Instead, as she entered their large, split-level, home, she was struck by a sickening smell that hung heavy in the winter air.

"I thought he must have cooked and left something on the stove," she would say in a rare interview years later. "But I went in the kitchen and I didn't see anything there."

She followed the strange odour to an upstairs bedroom where she found her husband. Once the most feared fighter in America, he was sprawled at the foot of their bed wearing only his underwear. His body was bloated - he had been dead for at least six days - and there was dried blood streaking from his nose. Geraldine led the couple's seven-year-old son, Daniel, downstairs and told him to wait there.

She did not ring the police for several hours. According to a Las Vegas police report, she first called her lawyer and then tried desperately to reach a doctor. When one finally arrived he could do little more than confirm what she already knew. Charles "Sonny" Liston was pronounced dead at the scene. Why he died remains one of sport's most enduring mysteries.

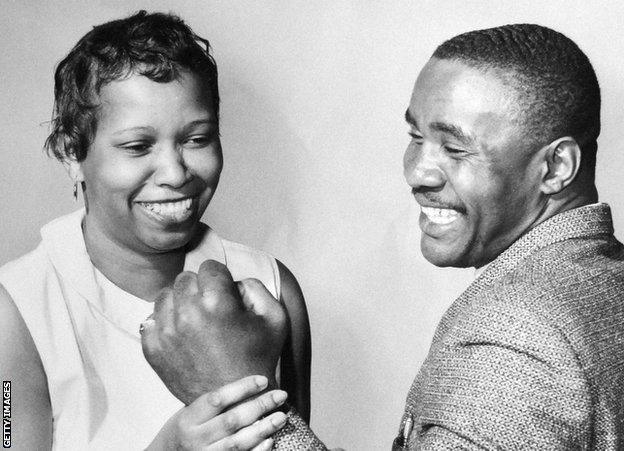

Geraldine married Sonny Liston in 1950

It was well after midnight when the police arrived at the Liston house, which sat in an affluent, largely white, suburb called Paradise Palms.

The doorstep was cluttered with days' worth of unopened milk bottles as well as a stack of unread Las Vegas Sun newspapers, which investigators would later use to determine the exact day Liston had died. Several windows had been left open, but this did little to ease the stench of rotting flesh.

Sergeant Dennis Caputo, now 69, was one of the first officers to arrive. "The call came over despatch and we were aware that it was the Liston residence," he tells the BBC from his home in the city. "But in Las Vegas it wasn't unusual to get high-profile calls like that. For me, it wasn't a big deal."

He quickly began a thorough search. "It was a very nice house," he says. "Well-kept and orderly. I got the feeling it hadn't been lived in too much." There was nothing to suggest - at least on first sight - that something sinister may have happened. "There were no apparent signs of forced entry, no visible weapons, and no signs of a struggle," he recalls.

Sgt Caputo was escorted to the master bedroom where he found a small bag of marijuana and a glass of vodka alongside Liston's prone corpse. "He was wearing a T-shirt and boxer shorts and was in a state of decomposition," he says. While some accounts of Liston's death say a revolver was discovered in the bedroom, Sgt Caputo remembers things differently: "There were no visible wounds and no weapons were found."

Shortly after, he discovered a small amount of heroin in the kitchen but no syringe. "The kitchen was spotless except for a penny balloon on the counter," he says. "It was common knowledge that these kind of balloons were used to transport illegal narcotics. I will also say that it was pretty well-known that Liston was a part-time user."

Former Las Vegas Police Sergeant Dennis Caputo was one of the first officers to arrive at the scene of Sonny Liston's death

Most reports of Liston's death state that fresh needle marks were found on his arm. While Geraldine has disputed that her husband ever used drugs, some have alleged that she may have cleared the syringe away. "Geraldine and her attorney were in the house for an unknown period of time before we arrived," Sgt Caputo says. "I did find it odd that [she] called her attorney when the body was discovered rather than the police."

But others - including some of Liston's closest friends - say that he would never have used heroin because he was terrified of needles. "He wouldn't even go to a doctor for a check-up, for fear some doctor would want to stick a needle in him," his former trainer, Johnny Tocco, told the Washington Post in 1989.

Liston's body was eventually moved into a waiting ambulance. According to some witness accounts, his vast weight proved too much and he was dropped several times. It was an undignified exit, reminiscent of a felled boxer being carried out of the ring.

An autopsy would later reveal that traces of morphine and codeine - of a type commonly produced by the breakdown of heroin - had been in Liston's system. But there was not enough of it to definitively state that he had died of an overdose. Officially, the Clark County Coroner ruled that the boxer died of natural causes, specifically lung congestion and heart failure.

It was a verdict that - in the eyes of many boxing fans - only raised more questions. How could a man - still active as a professional fighter - suddenly drop dead? Was it possible that he could have been training while using hard drugs? And wasn't he afraid of needles anyway?

The strange circumstances of Liston's death - and the murky life he had been living at the time - have fuelled fierce speculation about what may have happened to him. Some, such as Sgt Caputo, accept the coroner's verdict of natural causes. But many still struggle to do so, and the prevailing theory - one that has only gained traction since his death - is that his criminal connections came back to bite him and he was murdered by the mob.

"The whole Liston story is so shrouded in mystery," says Rob Steen, who wrote a biography of the boxer. "There's so many people who died who might have been able to shed a little bit of light on it.

"But I don't think anyone ever really believed he had a heart attack."

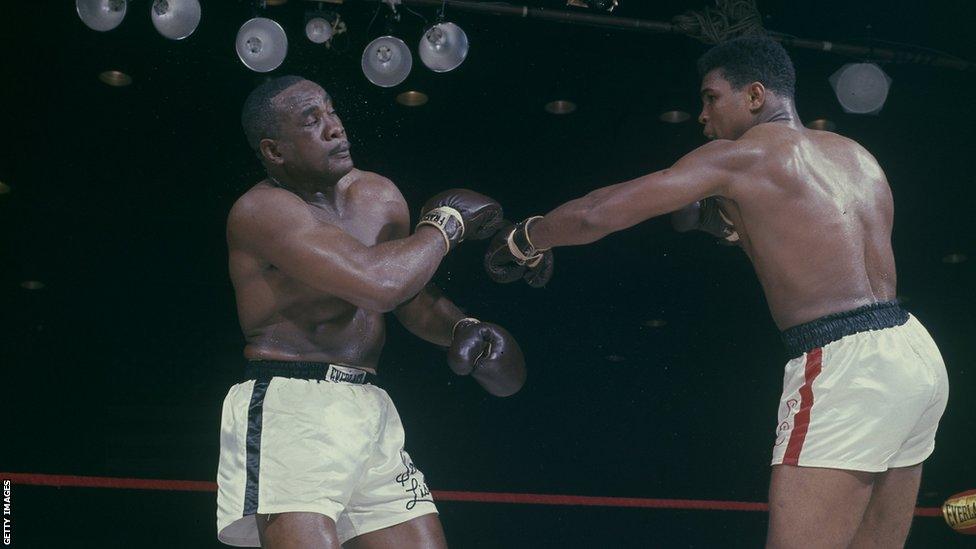

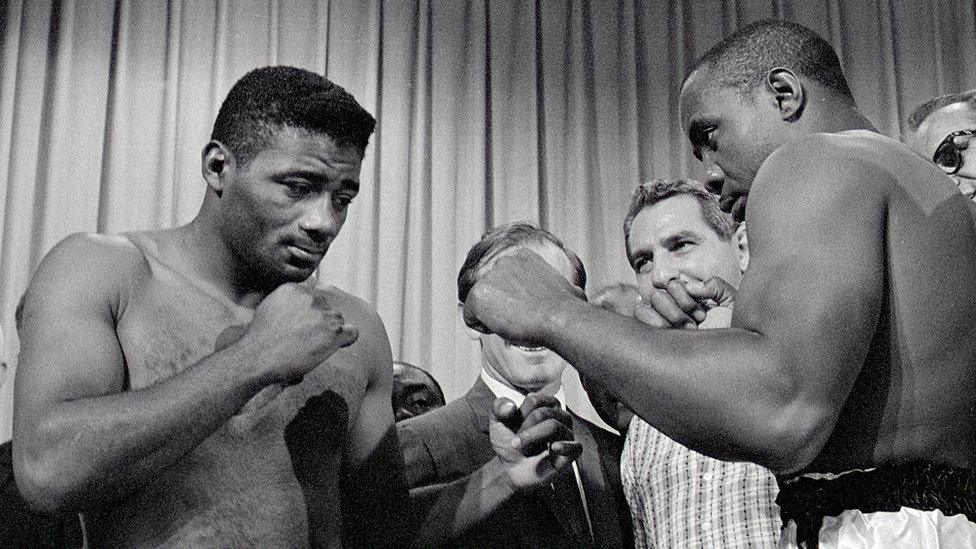

Sonny Liston lost his heavyweight title to Muhammad Ali in a major upset in 1964

The mystery surrounding Liston's death is in some ways fitting. This is a man, after all, whose most basic details were the subject of speculation. He was born in rural Arkansas to a family of sharecroppers - the 24th of 25 children - but birth certificates were not a legal requirement at the time and so Liston did not have one. It is believed he was about 40 when he died, but some have suggested he may have been closer to 50.

As a child he was beaten at home and he struggled at school. "We hardly had enough food to keep from starving, no shoes, only a few clothes, and nobody to help us escape from the horrible life we lived," he would later say. "We grew up like heathens."

The young Liston was teased relentlessly because he was unable to read or write and, when his family upped sticks and moved from Arkansas to St Louis, he abandoned education and turned to crime. "The police were forever chasing him," says Steen. "Apparently they had his photograph stapled to the inside of the visor in their cars. He was in trouble with the police quite a bit."

In one early incident, he made his disdain for the police clear while demonstrating his remarkable strength. "He started a fight with a cop, beat the cop senseless, snatched his gun, picked him up and dumped him in an alley," recounts Jonathan Aig in Muhammad Ali: A Life. "[He] then walked away smiling, wearing the cop's hat."

His first serious conviction was for armed robbery when he was about 22. He was sent to Missouri State Penitentiary where his natural athleticism and talent for fighting were soon spotted by Father Alois Stevens, a Catholic priest who also ran the prison gym. "He was the most perfect specimen of manhood I had ever seen," Stevens later told Sports Illustrated. "Powerful arms, big shoulders. Pretty soon he was knocking out everybody in the gym. His hands were so large! I couldn't believe it."

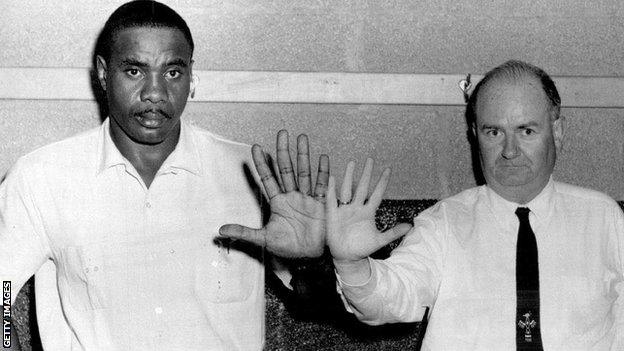

Liston shows off his huge hands - his fists measured 15 inches around and were the largest of any heavyweight champion

After two years in jail he was freed on parole and - in 1953 - he turned professional. But his newfound freedom was short-lived as the mob, which would go on to dominate his career and later life, quickly claimed him as their own. They would - according to boxing historians - manage his every fight and control his every earned dollar.

"When he comes out of jail, because he is such a muscular figure, such a powerful figure, people don't really want to fight him," Rob Steen says. "In order to get the kind of fights that he needs to progress as a boxer he needs 'heavyweight representation', shall we say."

"This is where the mob comes in," Steen continues. "They manage to create fights for him that other people couldn't because they use their muscle. He's the last great investment the mob make in boxing."

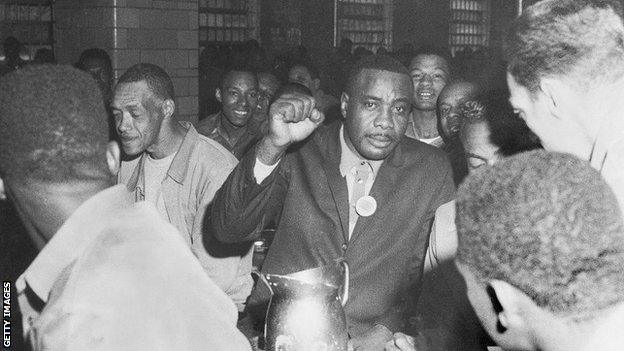

Sonny Liston pictured visiting Missouri State Penitentiary - where he once served time - ahead of his first fight with Muhammad Ali in 1964

Mobsters were attracted to Liston because of his formidable talent. After all, for a fighter to be a worthwhile investment he needs to able to win. With an eventual record of 50 wins and 4 losses with 39 knockouts, Liston's power was frightening. His left jab was one of the most concussive ever seen in boxing and his stare was one of the most menacing, burning through opponents in the minutes before the opening bell.

"Of all the men I fought in boxing, Sonny Liston was the scariest," Muhammad Ali would later say.

"Liston does not merely defeat his opponents," Jonathan Aig wrote of the fighter. "He breaks them, shames them, haunts them, leaves them flinching from his punches in their dreams."

Liston's frightening reputation was something he exploited as he went on an impressive run of wins in the late 1950s and early 1960s. But it was also stoked by a racist press keen to portray him as the kind of brutish black man 'White America' so badly feared.

"He's arrogant, surly, mean, rude and altogether frightening," the famed New York Times columnist Arthur Daley wrote. "He's the last man anyone would want to meet in a dark alley." Reporters often used thinly-veiled racist terms - 'gorilla' and 'beast' - in their descriptions of him. When he was set to face Floyd Patterson for the heavyweight title, President John F Kennedy went so far as to urge Patterson to find an opponent with "better character".

Sonny Liston stares down his opponent - Floyd Patterson - ahead of their rematch in 1963

The public and the press did not take to him. Liston was cast as an outsider, loathed for his outlaw past and his criminal connections.

This dislike reached its peak when he destroyed Patterson - who was widely liked - in two minutes and six seconds to win the heavyweight crown in 1962. When he returned home to Philadelphia, he hoped a crowd would be there to welcome him. "He rehearsed his speech with the journalists on the flight," Rob Steen says. "He gets to the top of the stairs when they arrive ready to greet everyone with this speech about how he's going to be a great role model for the black race - and there's no one's there! It makes him shrink back into his shell."

It was not just 'White America' that rejected him. The civil rights movement did too - in large part because of his ties to organised crime. "Liston was about the last person the movement wanted to signify black achievement," Steen explains. "He was illiterate, he'd been in prison, and he'd supposedly beaten up striking workers for the mob where he was living. He'd sold his soul to the mob in order to get proper fights. His management was the mob."

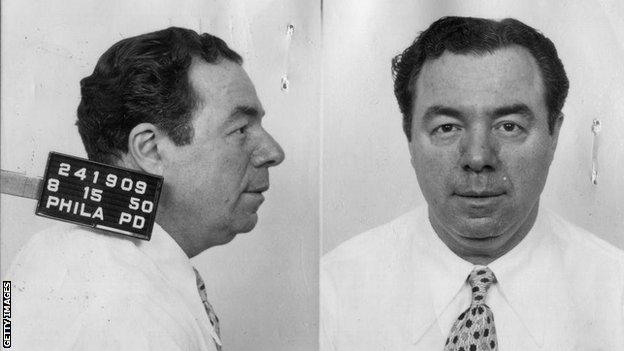

A mugshot of Frank 'Blinky' Palermo - who managed Liston in his early days and was later jailed for conspiracy and extortion

There was John Vitale in St Louis, a mob boss for whom Liston worked ostensibly as a chauffeur but - more accurately - as an enforcer and leg-breaker. In the early days of his professional career, he was managed by Frank 'Blinky' Palermo, an associate of the notorious mafia hitman Frankie Carbo. "The trouble with boxing today is that legitimate businessmen are horning in on our game," Palermo once famously said.

Ultimately, as David Remnick wrote in his book about Muhammad Ali's early years: "Liston was the last great champion to be delivered straight into the hands of the mob." Some would say these connections followed him to the grave.

It wasn't until Liston lost his title to Muhammad Ali - then known as Cassius Clay - in 1964 that his status as the most feared man on the planet began to wane. But it was the pair's controversial rematch the following year that did the most damage to his reputation.

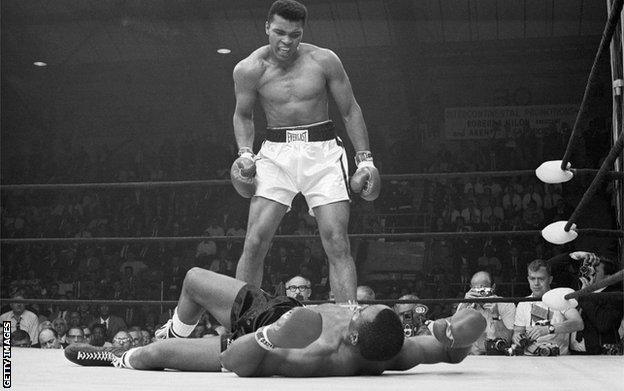

Just 104 seconds into the fight, which took place in the tiny town of Lewiston, Maine, Liston went down after an apparently innocuous punch that few people at ringside even saw. The infamous 'phantom punch' enraged Ali - who screamed at the downed Liston to get up and continue. "You're supposed to be so bad! Nobody will believe this!" he cried. Sprawled flat on his back, Liston would roll and stumble and then roll again. That scene, of Ali imploring Liston to get up, would produce one of the most iconic photographs in sports history.

Muhammad Ali stood over Liston shouting at him to get off the canvas

The phantom punch has been analysed and debated down to its finest details. While many believe it was a solid right-hand that caught Liston, many others have argued that he took a dive because the fight had been fixed by the mob. Even Geraldine had her suspicions: "I think Sonny gave that second fight away," she told a TV journalist 35 years later. "I don't know whether he was paid [but] that's my belief, and I told him."

Whatever the truth, the public jumped at the opportunity to label Liston corrupt. He was embarrassed on boxing's biggest stage amid fierce accusations that he was little more than a mafia stooge.

In the years following the Ali loss, Liston moved to Las Vegas and reverted to form. He was virtually broke - his earnings likely skimmed by his mob handlers - and he was forced to make money outside the ring in the only way he knew how. Allegedly, according to those who knew him, by working for the city's loan sharks and drug dealers.

"Sonny comes to Vegas after this unimaginable public humiliation," says Shaun Assael, who investigated the final year of Liston's life for his book: The Murder of Sonny Liston. "It's either a public humiliation of his own doing, meaning that he took a dive for whatever gains had been negotiated, or he was felled by Ali's huge hook. Either way, the public's verdict was that Sonny was a bum."

Despite his lowly public standing, Liston was hopeful he could resurrect his career. He went on an impressive run of victories after his two defeats to Ali - winning 14 fights in a row. He even spoke of recapturing his heavyweight title. But, in 1969 - about a year before his death - he fought his old sparring partner Leotis Martin and was knocked out in brutal fashion. It extinguished any lingering title hopes and he was left penniless and adrift.

"Vegas is a deeply segregated town at that point," Assael explains. "Sonny starts to spend more time in the segregated west side and begins to lead a double life."

On the one hand there was the family time he would spend at his home in Paradise Palms. This would be interspersed with occasional public appearances at the city's casinos, where he would cash-in on his celebrity status by shaking hands and signing autographs.

Liston was known to cruise around Las Vegas at night in his conspicuous pink cadillac

But a different side to Liston would come out at night. He would cruise over to the west side in his conspicuous pink Cadillac. "There were a lot of places that were run down and others that were struggling to keep their heads above water," Assael says. "Sonny was a fixture in a lot of these places. His routine largely involved drinking and, as I discovered, dealing some cocaine out of a casino and also getting involved in heroin. This double life begins to weigh on him."

Liston was associating with some of the city's darkest characters. "There was a drug raid on the home of a beautician named Earl Cage who was also dealing drugs," Assael says. "Sonny was there, and when the police raided it [they] thought they were going to have to shoot him because he wasn't backing off."

The boxer once ran into an old acquaintance, Moe Dalitz, one of the most powerful mob figures in the city. "As a joke, Liston made a fist at Dalitz and cocked it," writes David Remnick in his book King of the World. "Dalitz turned to Liston and said: 'If you hit me, you'd better kill me, because if you don't, I'll make one telephone call and you'll be dead in 24 hours.'" Perhaps it was a premonition. Before long, Liston would be dead and the shadow of the mob would loom large over his corpse.

"He was moving in dangerous circles, even without organised crime," says Michael Green, a professor of history who has studied Nevada and the mob extensively. "He appears to have had involvement with drugs and if you're involved with drugs, then you're dealing possibly with the mob."

Sonny Liston poses for the camera in 1961

So could the mob - or at least drug dealers and criminals - have been involved in Liston's death? And why would they have wanted him dead? The most common theory is that his boxing career at the top-level was over by the time he died. This meant he was no longer a profitable investment for the mob but, owing to his long career in their grasp, he simply knew too much to be left alone.

"My inclination is that he was bumped off because he was of no use to the mob anymore," says Rob Steen. "He knew things that may have come out, or indeed have come out over the years, and they decided it was too big a risk having him around."

"I'm not alone in this theory by any stretch of the imagination," he continues. "After the second Ali fight, when his life was in a bit of turmoil, he was apparently less than respectful to a particular member of the mob from Cleveland. This guy was very angry that he had not been shown sufficient respect by Liston and that was the trigger. That made the powers that be decide that they didn't need him around anymore."

Michael Green, who is also a board member at the Las Vegas Mob Museum, believes the growing concern over what Liston knew may explain his death. "Hits on mobsters were generally in connection with the fear they were going to talk," he explains. "If you go back throughout [Liston's] career, and the mobsters who were involved in it, and what he had done as an enforcer, he was the man who knew too much."

What - for example - did Liston know about the second Ali fight and the 'phantom punch'? Could he have been about to speak publicly about boxing's corrupt underbelly?

Green continues: "The alternative was the fear that they would not do what they were supposed to do. Perhaps they wanted Liston to do something in particular and he wouldn't. That is always a possibility." Some boxing historians have alleged that Liston refused to throw his final fight with Chuck Wepner, which he won just months before his death. A refusal of that kind would have no doubt gone down badly with any criminal handlers.

"Evidence suggests there were a lot of people who wanted to see him dead," says Shaun Assael. "I do believe he was murdered. There were five or six people who could have done this."

The nature of Liston's death - quiet, relatively unbloody and exceptionally murky - does not fit with the typical image of a mob hit. After all, the accepted view is that the mob would kill with the intention of sending a message and, even today, it is unclear what exactly happened to him. "I am inclined to suspect it's a mob hit, but at the same time it gets difficult to put it in the perspective of other mob hits," says Michael Green. "That isn't the way the mob normally would have done this."

Sonny Liston pictured with the notorious London gangsters the Kray twins in 1965

But Green says Liston's death does match with the mob's transition towards a new kind of subtlety. "The mob itself was changing," he says. "This had a combination of subtlety - you don't have a body with 10 bullets - and a lack of it, because he was just found dead. This suggests it could have been a mob hit."

So what can be made of the needle marks on Liston's arm and the heroin in his house? What if the boxer simply overdosed? There has been speculation among some boxing writers and mob historians that Liston was killed by an enforced heroin overdose. "The way he was killed was a typical mob sort of execution - making it look as if someone had taken too much heroin," says Rob Steen. This would explain how a man supposedly terrified of needles could end up with marks on his arm and heroin in his blood.

Of course, there are also theories that lack this level of intrigue and mystique. "It should be pointed out that Sonny had a car accident shortly before his death," says Shaun Assael. "He was gripping his chest and so on and so forth. There are people who think that his death was the result of him medicating himself from pain from the car accident." Others believe it may have been caused by cardiac arrest or a stroke.

Whatever the theory, Liston's mysterious death marked the end of a life pockmarked with shadowy figures and secretive criminal activity. It has haunted boxing ever since - serving as a morbid reminder of the characters that used to inhabit its ringside seats and smoky backrooms. "His death did a great deal to damage the image of boxing," says Rob Steen. "In a sense, he is a symbol of the way the world once was. His death is a signpost as to how bad things were and how fortunate the sport was that Muhammad Ali came after him."

"You don't find other boxing champions dying in that way," he adds. "But, then again, boxers usually didn't have the depth of involvement with the mob that Liston had."

Sonny Liston's grave in Las Vegas carries the simple epitaph 'A man'