Joshua v Ruiz II: The tiny margins between defeat and glory

- Published

Anthony Joshua - I'll beat Ruiz this time

Ruiz v Joshua |

|---|

Venue: Diriyah Arena, Saudi Arabia Date: Saturday 7 December |

Coverage: Live BBC Radio 5 Live commentary with live text commentary on the BBC Sport website and app |

The legendary light-heavyweight Archie Moore described the feeling as "walking the street of dreams", the moment a boxer is transported to a twilight world of scrambled senses by the force of a single punch.

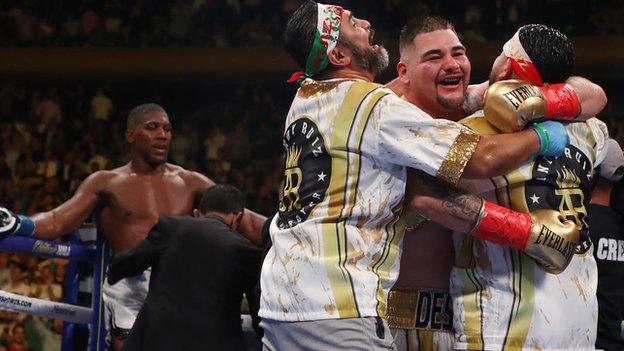

Anthony Joshua went down that road in New York last June and, not for the first time, the course of heavyweight boxing history was altered in a split second.

At his training base in Sheffield this month, Joshua recalled how the left hook landed by Andy Ruiz Jr in the second minute of the third round marked the beginning of the end of his debut at Madison Square Garden. There was more than half the fight remaining - the referee waved it off in the seventh - but in Joshua's mind it was all over much sooner, along with his reign as world champion.

Earlier in the third round, Ruiz had been floored by a right-uppercut, left-hook combination and Joshua went looking to land the same two shots twice in the following 20 seconds. On the second occasion, as Joshua swivelled into his left hook, Ruiz got there first with an almost identical punch. Joshua wobbled away and seconds later fell to the canvas.

There would be three more knockdowns suffered by Joshua but he is adamant that the critical damage was inflicted on that first visit to the canvas. "I never recovered," he told me during a reflective interview at the English Institute of Sport.

Split seconds and fractions of inches separate success and failure across world-class sport, but in few arenas is the capacity for turnarounds as dramatic as in the ring, especially at heavyweight. Ruiz was two rounds and a knockdown behind before connecting with the punch which ultimately built a new house for his mother.

Last weekend, the judges' scorecards showing a clear advantage for Luis Ortiz were reduced to wastepaper in an instant when the wily Cuban left his chin in the path of a Deontay Wilder right hand in the seventh round of their showdown for the WBC title in Las Vegas.

The 25th anniversary passed recently of George Foreman becoming the oldest world heavyweight champion, at the age of 45, after catching Michael Moorer with a similar punch in the same MGM Grand Garden Arena. And the right hand again was the clincher for Rocky Marciano when he wrested the world title from Jersey Joe Walcott in the 13th round in Philadelphia in 1952. Like Wilder, Foreman and Marciano were adrift on the scorecards.

Joshua's downfall was all the more surprising given the recovery mission he had mounted after being knocked down heavily by Wladimir Klitschko at Wembley Stadium more than two years ago. Back then, Joshua was composed enough to tell his trainer Robert McCracken that he had "taken a round off" in the eighth in order to regroup.

'I have been so happy with how everything changed' - Ruiz Jr

Against Ruiz, Joshua was entitled to attempt to capitalise on his success in inflicting the first knockdown Ruiz had ever suffered. But in engaging in a firefight, Joshua introduced an element of Russian roulette into the equation. He has often mentioned his admiration for the five-round war between Foreman and Ron Lyle in 1976 and suddenly found himself in a modern-day interpretation, if not quite as high octane. Instinct and emotion, so controlled against Klitschko, seemed to cloud Joshua's judgement against Ruiz in relation to the most important distinction a fighter makes in mid-storm: when to take aim and when to take cover.

Thomas 'Hitman' Hearns once said: "For a long time, my pride was too high. But I learned. When you get in trouble, grab hold. Ride it out. Any man can get hurt. And when he does, he must learn how to survive. Or else."

Against that background, with such tiny margins of error, it is remarkable that the likes of Floyd Mayweather and Joe Calzaghe got it right every time: the split seconds and fractions almost always in their favour. Yes, they were in lighter weight divisions and the power ratio might be lower but the punch output in terms of numbers is much greater. And Mayweather suffered just the one (highly questionable) knockdown during a career in which more than half his 50 fights were world title contests.

In training, Mayweather and Calzaghe placed heavy emphasis on boxing skills and drills: bags, pads and sparring being every bit as important as strength and conditioning. In our recent interview in Sheffield, Joshua said his focus for this fight had changed. "More boxing," was the instant response when I asked him what modifications had been made in the gym.

Joshua had never lost before meeting Ruiz in New York on 1 June

Over the past two and a half years, Joshua has played his part in a heady era. His fights against Klitschko and Ruiz, alongside Wilder-Ortiz I and Wilder's draw against Tyson Fury, should be recognised now - rather than wait for distant perspective - as the nucleus of a special period in the heavyweight division. As for the future and the scope for more of the same, it could be argued that Fury, Joshua, Ruiz and Wilder are all still improving.

Ruiz' only defeat in 34 fights was a debatable points loss against Joseph Parker in New Zealand three years ago. Parker enjoyed enough success at long range to eke out a split decision but Ruiz won virtually every exchange at close quarters. His fast hands tilt the odds his way when standing toe to toe and Joshua's strategy in this department could be crucial to the outcome of the rematch.

Even some of the very best have needed a second crack. Lennox Lewis sustained savage knockouts by Oliver McCall and Hasim Rahman but won the return fights, with the win against Rahman in 2001 ranking high among Lewis' finest performances. The response to adversity, warding off the potential for gun-shyness and a severe threat to his legacy, is what Joshua must emulate among the dunes in Saudi Arabia.

- Published7 December 2019