Test cricket: Does the oldest form of the game have a future?

- Published

- comments

David Bond looks at the long-term future of Test cricket

It might seem odd to be contemplating the future of Test cricket in the middle of a sold-out Ashes summer.

But the undimmed appeal of five-day contests between England and Australia only highlights the wider problem in other countries.

In India, South Africa, Sri Lanka, New Zealand - and even to a certain extent Australia - crowds for Test matches are falling. Set against the growing popularity of Twenty20 cricket (particularly in India and Australia) there are concerns at the highest levels of the game that its most traditional format could die out.

For The Editors, a BBC programme which sets out to ask challenging questions, I decided to find out whether Test cricket, the longest and oldest form of the game, has a future.

If that sounds alarmist then don't take my word for it. This is what former England captain Andrew Strauss thinks: "If we are arrogant enough to assume that Test cricket will always be there, we are sowing the seeds of our own downfall."

But ask most fans and professional players and they will still tell you that Test cricket remains the pinnacle.

So what exactly is the problem?

On the playing side it's a question of money. The emergence of well-funded T20 competitions like the Indian Premier League and the Big Bash in Australia has shifted the financial balance of power away from Test cricket to the shortest form of the game.

Consider Forbes' 2012 list of the highest earning cricketers. Six of the top 10 are Indian with MS Dhoni the highest paid player in the world with earnings of $26.5m (£17.3m). The other four players in the top 10 are all Australian.

Compare that to the £250,000 to £400,000 annual salary paid to England's top players by the England and Wales Cricket Board, external as part of their central contracts programme.

Crowd attendances for Test cricket have been steadily declining for years across the globe.

For those players with the ideal skills for T20, the recent changes in the economics of the game have posed a difficult dilemma. Do they go for the cachet of Test cricket or the cash of T20?

During a recent trip to Taunton, I asked the Somerset captain and former England opening batsman Marcus Trescothick, external whether he would swap all his Test caps for the sort of money MS Dhoni earns from the IPL.

He told me: "My goal from an early age was to play for England and that's what I wanted to do. I'm probably a little bit clouded because I came at the back end of the T20 phenomenon so it was never really an issue for me. Maybe now? This is the question for the young kids."

What the next generation must decide then is whether it's really worth trying to juggle two different formats of the sport when the rewards in one so greatly outweigh the other. At the moment younger players still seem to want to do both and even those who have come to prominence in T20 try and develop their Test game. But how long will that go on?

Fans also seem confused at the current state of play. Many I spoke to at India's Champions Trophy game against the West Indies at The Oval in June said they preferred Test cricket, or at the very least felt it was more important. But if that's how they feel how does one explain the empty grounds for some Test series, especially in India of late? Is it just a factor of modern life? Are we all just working too hard?

If we are - and British workers are above the European average when it comes to working hours - then how is it that the first four days for all five Ashes Tests are sold out? There are clearly different attitudes in different countries but, given this is international cricket, how on earth is one ever going to reach a consensus?

This is a debate that could do with some proper analytical data. And yet the International Cricket Council, external is unable to make any available despite hiring a company, Future Sport and Entertainment, to look into viewing figures for Tests around the world.

In the absence of hard evidence, is it any wonder that it all seems a bit of a muddle?

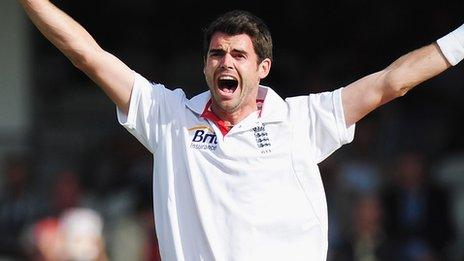

Anderson focused on cricket ahead of Pakistan reunion

At the moment most international cricket boards seem content to shoehorn as many one-day matches and T20 fixtures as they can into seasons already crowded by busy Test schedules. This way they can guarantee any gate income lost for Tests is subsidised by the shorter forms of the game.

But at what point will one of the boards say that this is the tail wagging the dog? England's 2012-13 tour to India featured four Test matches and two T20 internationals. How long until that switches around?

So what can be done to redress the balance?

Clearly the ICC has to use its power to force countries to continue to prioritise Test cricket.

It is exploring innovations designed to make the five-day format more attractive for fans and compatible with the demands of modern working life. For example, day-night games using pink balls under floodlights is one option.

And from 2017 the four highest ranked Test playing nations will battle it out for the World Test Championship, with the inaugural tournament to be played in England.

But while it's a simple and attractive idea it is bedeviled with complex problems. What happens, for example, if the two semi-finals and the final end in draws? How is the winner decided? Will a championship won through higher run rates or some other such variable really satisfy the fans and TV companies it is aimed at?

David Richardson, the ICC's chief executive, says he remains optimistic about the future of Test cricket and argues the new audiences and players being attracted by T20 could help strengthen rather than kill off Test cricket.

New Zealand Test captain Brendon McCullum earns millions playing T20 in the Indian Premier League.

"Yes, maybe the youngsters of today see the bright lights of the IPL and World Twenty20 and they're attracted to the game, which is actually what we want to achieve," he told me. "Cricket really probably if we'd stuck simply to just Test cricket might be in danger of becoming extinct down the line."

At the moment the ICC is hedging its bets, juggling all formats (including the 50-over game) to maximize revenues despite the pressure that puts on players to perform on a treadmill of seemingly endless fixtures.

This seems a risky approach that could ultimately devalue all forms of the sport.

But the reality is that whatever strategy the ICC sets, this is a debate that will ultimately be determined by the market, and most importantly the market in India. And if the market wants T20 then Test cricket is bound to suffer.

In a decade's time we could look back on the T20 boom as a short-lived craze. After all, Test cricket has faced similar threats during its long, rich history and has always found a way to survive.

It can do so again but, as Strauss says, it can't afford to be complacent.

The Editors features the BBC's on-air specialists asking questions that reveal deeper truths about their areas of expertise. Watch it again on the BBC iPlayer.

- Published22 March 2012

- Published25 November 2011

- Published21 November 2011

- Published12 November 2011

- Published26 August 2013

- Published10 March 2019

- Published18 October 2019