James Taylor: 'I thought I was going to die'

- Published

Taylor on life after cricket

"I had my usual morning nap, and then did the warm-up. Towards the back end of the warm-up that's when my chest started getting tight. Apart from being tight it was beating at a million miles an hour. We were doing just a couple of routine catches and throws.

"My heart was going wild at a funny rhythm. It was probably only about four degrees, really cold, and I got inside. Sweat from me is hitting the ground hard. So I knew I wasn't right.

"And that's when I thought I was going to die."

This is how England cricketer James Taylor recounts the day his life changed for ever. The day he survived.

It was a pre-season match for his county, Nottinghamshire, at Cambridge University in the first week of April. He'd had no warning. There had been no virus, no signs, no symptoms. Quite the contrary.

"Everyone thinks it was found in a routine heart check which wasn't the case," the 26-year-old tells BBC Radio 5 live. "I was feeling good as gold, in fact my lead-up to this season was probably the best I've ever felt - mentally and technically."

By 5pm he was in hospital. He'd remain there for 16 days after being diagnosed with Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC)., external

The scans, the monitors, the care, the environment of support for his friends and his family; Taylor will never forget Nottingham City Hospital.

"They did save my life and that's a fact," Taylor says. "Nobody really appreciates what they do in the NHS.

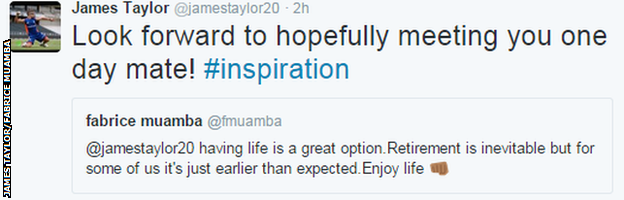

James Taylor posted on social media shortly after news of his retirement was announced

"They constantly get slated and almost bagged in the press. Until you've had an experience where your life can be taken away from you, you don't realise what they actually do.

"And the way they looked after me and catered for me at my time of need when I was going to die was unbelievable. And I owe so much to them and I will continue to support them in any way I can."

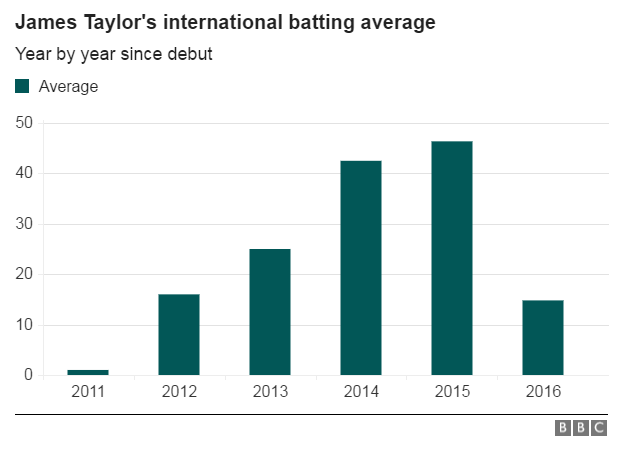

Taylor was in his prime as a cricketer when his blossoming career was abruptly cut short.

His one-day record, for example, was outstanding - his List A [one-day] batting average was the fourth best of all time,, external just behind legendary duo Michael Bevan and AB de Villiers, and India's Cheteshwar Pujara.

His Test career was flourishing, a place in the England team for the summer was virtually assured - he was widely regarded as one of his country's best players against spin, in particular, and had made the short-leg fielding position his own with some spectacular catches under the helmet over the winter.

Confident, popular, dedicated to improving his technique and fitness - Taylor had won everyone over.

But now he can't be a cricketer anymore. How, I ask him, has he possibly adapted to that?

"I think that's been the hardest bit," said Taylor. "When the doctor told me, I was in hysterics at first.

James Taylor tweeted 24 hours after news broke of his retirement in April

"But then he told me that the majority of these cases are only found out in the post-mortem. I almost stopped crying at that point and felt more lucky that I'm in a position to tell this story now."

In other words most people never find out they have this condition because they are dead when it is diagnosed. It seems likely that Taylor only survived the initial attack because he is so fit.

Having kept the condition and the diagnosis secret for a week, a media release was then circulated. Information was kept simple but the key fact was there - the world knew that Taylor had been forced to retire.

So, in hospital, Taylor was able to read what the world thought about it, largely through messages on his Twitter feed.

"I occasionally lay in bed - like I'm sure a few people have done - and wondered what it would be like if I died. Who would turn up to my funeral? And what would people say?

"And the outpouring of emotion to me was like I'd died. It was quite dramatic in that sense, but it was amazing.

"Once the release had been made to the press and the messages started flooding in, it took my attention away from my career and me not being able to do the thing that I loved ever again.

"Just one of those messages came from footballer Fabrice Muamba. His was probably the first public case of this kind.

"He was a star, he tweeted me almost straight away and direct messaged me as well so in time I'd love to meet him. There's not many people who know what you're going through and he certainly does."

James Taylor responded to encouragement from Fabrice Muamba

What Taylor is going through is only just beginning. As we sit and talk, he carries a black case on his lap.

It's attached to a long shoulder strap. Initially I'd thought it was a pair of binoculars, perhaps he'd brought them to watch Nottinghamshire train? After all, we were using a room in Trent Bridge overlooking the outfield.

I was wrong. In fact it was a defibrillator., external It never leaves Taylor's side.

Underneath his shirt he wears something called a life vest. It is monitoring his heart and, in effect, communicating with the defibrillator.

"Ultimately it's going to save my life if required," he says. "If my heart goes into the rhythm and the pace that it went at when my first kind of attack happened then this will go mental, put it like that.

"It will siren, it will talk to me. If I'm conscious I can manually stop the shock that will hit me and I will get to hospital as soon as I can.

"But it if I'm passed out on the floor then it will kick in and give me a huge electric shock and bring me back to life as any external defibrillator will do if needed."

In June Taylor hopes to have a defibrillator surgically fitted inside him. That will make life easier, to an extent.

But the curse of his condition is that exercise, typically, makes it worse. A young man, famed for his fitness, now has to face a future of simply not knowing what his body can cope with.

"At the minute I certainly can't do any exercise, except walking," he explains. "Like anybody I will get used to my body and what it can do and to what extent it can push itself.

"But this condition itself is accelerated and is made a lot worse with the more exercise and the more pressure the heart is put under.

"So the more exercise I do the worse it will potentially get, which isn't ideal considering I've never sat still for more than half an hour... let alone 16 days in hospital. As time goes on, as I recover from the operation, I will discover to what extent I can exercise."

Taylor now knows that in 90% of cases ARVC has an hereditary link. He is hoping that he is in the 10%.

Clearly then he would lose the worry of the condition affecting family members either current or future.

When we speak, he has not yet formed an opinion over whether heart screening could or should be extended - he has had more than enough to try to come to terms with.

But Taylor is certain that he wants to support the NHS and the British Heart Foundation in the future. His own role in cricket is more sensitive.

I ask him how he would feel being around the sport he loves, knowing he can no longer participate.

"I will only know when I'm around it again," he says. "But when I was lying in hospital people said to me 'it must be so hard for you, you must be going stir crazy'.

"I was like: 'not really', because I know that's where I have to be. I have to be in hospital. That's the same with cricket.

"Yeah, I'm desperately wanting to play but the fact I know I can't makes it a little bit easier. So I just hope that at some point, or in some way, I can still help in cricket.

"It's a mad passion of mine and I know I have something left to give in whatever capacity. It's something that I love the most, and that's the hardest thing for me.

"Even when I played my first Test match at Lord's I was supposed to be playing a club final that same day. Had I not been picked I would have been playing in that club final. That's how much I love the game.

"I will desperately miss not being able to play it but I do really enjoy helping people in any way that I can, so fingers crossed I'll be involved in some way."

Mullaney 'numb' at Taylor retirement

While the medical staff deal with his physical condition, the task of keeping Taylor positive has fallen to those closest to him.

"I'm fortunate enough with the people I have around me, the group of people I've surrounded myself with that has made this so much easier," he says.

"I know that if I'd pushed a lot of people away on my journey so far I would not be as mentally stable as I am now. During cricket I've always tried to surround myself with good people because I know that's important. I'm just grateful that they've stuck by me through this tough time and helped me through it."

Cricket, in turn, now seems certain to cherish Taylor more than ever.

Offers are bound to arrive, but he is the only one who can learn to live with his condition, to live with the limitations suddenly imposed upon him.

He is also living something else: the knowledge that if the diagnosis had not come when it did, playing sport could have killed him.

- Published22 April 2016

- Published12 April 2016

- Published15 May 2018

- Published18 October 2019