Phillip Hughes' death: Have attitudes to the bouncer changed?

- Published

Data from CricViz shows that the use of bouncers has changed very little since Phillip Hughes' death

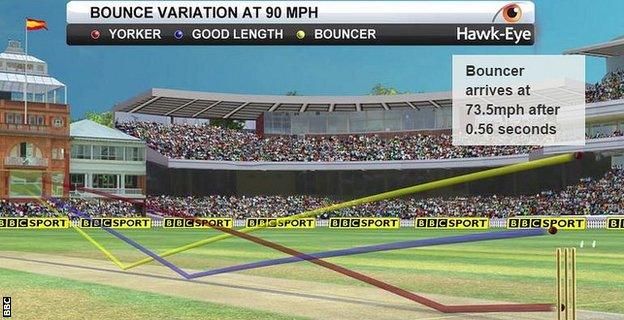

0.56 seconds. That's how long a cricketer will have to see, judge and play a 90mph delivery aimed at their body.

In that short space of time a batsman will have to run through a mental checklist. "Can I duck it? Do I swing the bat? Should I play it into the ground? Or do I turn, take my eye off the ball and accept the inevitable body blow?"

The issue of bouncers in cricket has grown since Phillip Hughes was struck by a short, fast delivery from Sean Abbott on 25 November 2014 in a domestic game in Sydney.

The Australia Test batsman died two days later, having never regained consciousness, and cricket took a back seat as a community mourned the loss.

And then came the questions. Was the bouncer, a well-known part of cricket's history, no longer safe for batsmen to face?

'Negligible decrease in bouncers per Test'

A bouncer, released at 90mph, arrives at the batsman's area 0.56 seconds after it has been released

Analysis from cricket statisticians CricViz shows there has been very little difference in the use of bouncers before and after Hughes' death - and that in Tests involving Australia, the number has risen slightly.

"We looked at balls which pitched 10 or more metres from the stumps, which is a rough estimate of intention to bowl a bouncer. With this, we saw a slight reduction in quantity after Hughes' death," product manager Will Luke told BBC Sport.

"The second set looked at deliveries which bounced 1.5 metres or more once it arrived at the batsman - in other words, the chest, throat or head-directed balls. With these, we saw a negligible decrease from 1.68 bouncers per Test to 1.62."

In Tests involving Australia, the number rose slightly from 1.65 per Test to 1.68 - a small increase at a time when their seam bowling has been the area where they have developed the most.

The use of bouncers has caused controversy since the Bodyline series in 1932-33.

England's bowlers in that series made a point of directing short, fast balls into the body - a tactic replicated with great success by the West Indies team of the 1970s.

The Bodyline series saw England bowl bouncers at Australia to try and intimidate batsman Donald Bradman

Criticism that the bouncer was against the 'spirit' of cricket led to the International Cricket Council limiting the number of bouncers in a Test match to one per batsman, per over in 1991.

On a practical level, changes were made swiftly after Hughes' death, with British-based firm Masuri adding extra protection to the back of the helmet where Hughes was struck.

Cricket Australia ruled that protective helmets should be compulsory for batsmen facing fast and medium-paced bowling, and the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) made a similar ruling in 2015.

Former England batsman Nick Compton, who was a close friend of Hughes, said the pursuit for the perfect helmet is a futile one, both from an engineering perspective and considering the principles the game has been built on.

"I'm against the new helmets. The helmet I wore, I'd worn for 10 years. If you get hit in the helmet, even with the new thing, it still would have missed that," he said.

Ultimately, it was not the tactical side of cricket that changed following Hughes' death, it was the mental side of the game; how does a cricketer readjust when they have seen what can occur from a second's misjudgement?

'It felt like the meaning had gone from cricket'

Compton described attending Hughes' funeral in Macksville as "something I needed to do". He played grade cricket in Australia with the 25-year-old and the pair went on to share a flat when the Australian played for Middlesex in 2009.

"He was revelling in this fresh, jubilant career. He was an exciting young player and I was kind of feeding off that," Compton told BBC Sport.

Compton, who took a break from cricket in June this year, said Hughes' accident did not affect his attitude on the pitch. Instead, it forced him to question what the game held for him as a whole.

"I felt like the meaning had gone a little bit. I had my own personal struggles up until that point and I felt like life at that stage was vacuous and a bit empty," he said.

"It kind of took away that bit of life that maybe I needed to get back to batting.

"I felt a bit lost and down so I guess, for me, it was about trying to get that passion and desire back."

'Take bouncers out and you lose the game'

Last month, an inquest concluded that no-one was to blame for Hughes' death. According to the coroner, the tragedy was the result of a "miniscule misjudgement or a slight error of execution" in playing an attempted pull shot.

It is a conclusion with which Compton agrees. Banning bouncers, he says, never crossed his mind in the aftermath of the accident.

"You can't build a suit of armour. This is not what cricket is about. The whole point is the fear and the pain and the hours you spend getting pinned. It's part of the game," he said.

"I grew up in a sport-mad place like South Africa where not shying away from the fear of a fast bowler bouncing you and getting in your grille was important, and I am very much that kind of person."

Former Australia captain Ricky Ponting had his cheek scarred by a bouncer from Steve Harmison during the 2005 Ashes

"If they take the bouncer out of cricket, I don't want to be involved," Test Match Special commentator Charles Dagnall added.

"You lose so much of cricket. It is an isolated incident and we all wish it never happened, but it is one incident.

"When you start talking about taking bouncers out of the game, you lose the game. They are part of the game's drama."

'There is nothing wrong with being menacing'

Tactically, very little has changed in the two years since Hughes' accident. Sledging, cited as "an unsavoury practice" in the inquest, is still prevalent. It is seen as a harmless tactic, designed to add an element of humour to the game.

"If you have boxers preparing for a fight, they say all sorts of rubbish leading up, but that's part of the entertainment," England bowler Katherine Brunt said.

"When they've touched gloves and they fight, there's a lot of respect before and after it, so it's part of the entertainment."

Concussion is an issue that cricket has yet to fully deal with, despite Australian cricket introducing a new concussion substitute, external for when a batsman is struck.

Players will play on even after taking a blow to the helmet. But where cricket has changed is the reaction of players, team-mates and opponents alike when someone is struck.

"There is a genuine concern now from players when they hit someone and it doesn't stop them doing it, but they want to make sure they are ok," Dagnall added.

"Bowlers get themselves into a state of high angst where they are hot, sweaty and mardy, and that's what makes a good fast bowler. But they now check and that wasn't always the case."

- Published27 November 2014

- Published4 November 2016

- Published27 November 2016