Viv Richards, Learie Constantine & Wes Hall: West Indies cricketers who charmed Lancashire

- Published

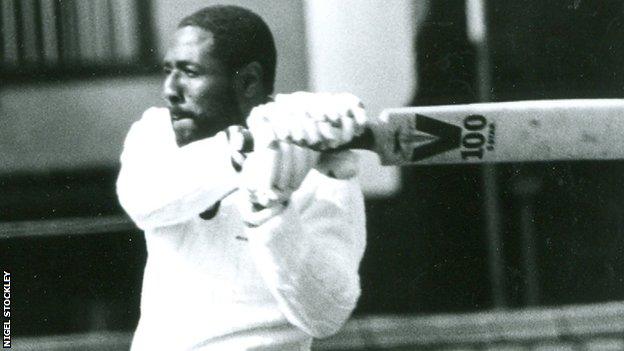

Viv Richards captained the West Indies in 50 Tests

"I was the fly in the coconut ice cream - very, very noticeable."

Throughout the 20th century West Indies' greatest cricketers dazzled on the humble club grounds of Lancashire.

Names like Viv Richards, Learie Constantine and Wes Hall are all etched onto the honours boards of the north west and they feature in a BBC documentary - Race and Pace - which is now available on iPlayer.

But their tales are about much more than cricket.

They are about race, fame, lifelong friendships, and unlikely accounts of when superstar cricketers from the other side of the world dropped into little Lancashire towns - and were taken to people's hearts.

Here are the stories of how the biggest black cricket stars in the world charmed the small white towns of Lancashire.

'Being first, I carried a burden' - the 1930s

The 14 teams in the Lancashire League were made up of 10 amateurs and one professional. Until 1928 the professional had always been white.

That year Nelson, a club heavily in debt, took a risk on Trinidadian Learie Constantine.

At £800 a season, he was thought to be the best-paid sportsman in the country.

"Schoolchildren were peeping through the window to see him," Nelson fan Edna Hartley said. "They were all lining up to see him because they had never seen a black man.

"They even came from Yorkshire to watch!"

Constantine's daughter Gloria Valere said: "People used to pass on the other side of the road when they saw him coming.

"He broke the barriers. They had been fed the idea black people were not really people, that they were less and were not very bright."

But in time perceptions changed, helped by Constantine's performances on the pitch.

Crowds of 7,000 flocked to watch the all-rounder play - an attendance which has never been matched. He led Nelson to seven titles in nine seasons and once took all 10 wickets in an innings for just 10 runs.

Constantine lived in the town for 19 years. He became a barrister, a knight and then Britain's first black peer - Baron Constantine of Nelson.

"I must admit that being the first coloured professional cricketer who had come to the Lancashire League, I had a job to do to satisfy people that I was as human as they were," Constantine said in 1966.

Watch Constantine in action and listen to his daughter, Gloria Valere, on "breaking barriers".

The black cricketer who broke boundaries

'Brilliant batsmen and furious fast bowlers' - the 1960s

Wes Hall took 329 wickets in his three seasons at Accrington and won the league title in 1961

Constantine was the first and many followed. By the 1960s 12 of the 14 clubs had a West Indian professional.

One star was Wes Hall, a fearsome fast bowler who played 48 Tests for West Indies between 1958 and 1969. In 1960 he signed for Accrington.

"Accrington was the defining moment in my life," Hall said. "I was away from home, had to live with people who were strangers and had to perform.

"I was like the fly in the coconut ice cream - very, very, noticeable.

"I had to be the type of person people love to be around."

And he was. Hall made a lasting impression on one Accrington teenager at the time, former England player, coach and now commentator David Lloyd.

"He would be the guy who really got me hooked on the game and the rest of the juniors who were here at the time," Lloyd said. "He gave me my first cricket bat."

Watch Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith reminisce about the era of 'the big quicks'

''You could see the fear in the batsmen's faces'' - Griffith

'Here comes the fear'

As the standard of professionals increased, so did the danger. The fastest bowler was another West Indies international, Charlie Griffith, who signed for Burnley.

In 1964 he took a league-record 144 wickets in a season as amateurs followed a week's hard graft by facing one of the world's best bowlers, genuinely concerned for their livelihood.

"They were obviously thinking 'I hope I get to work on Monday morning'," said Jack Schofield, a team-mate of Griffith. "If you didn't get out of the way you could get hit and get hurt."

Griffith himself added: "Before you got there you could see they were very nervous. Some batsmen came in and you could see in his face - the fear."

And some thought better of risking broken bones on the cricket field.

"I know the senior lads would look at the fixtures and book their holidays when you were up against one of the "big quicks", so they'd be having a fortnight off," Lloyd said.

Charlie Griffith was one of cricket's most feared fast bowlers and took 94 wickets in 28 Test matches for West Indies

'There were 365 pubs in Preston… we could only drink in one'

Hall and Griffiths celebrated their victories in the clubhouses of Lancashire, but elsewhere examples of racism were still clear.

Gladstone Afflick moved to Preston in 1960, but said he was only welcome in one of the town's 365 pubs.

"Preston was a horrible place because of people coming from out of town, not Prestonians. You couldn't go into town because they would all be on your back," Afflick said.

"They were coming in with cycle chains with wooden handles that they would hit you with."

But Afflick and pal Lewis Walker found their way into Lancashire life through cricket.

Amatuer side Jalgos Cricket Club was set up and featured amateur players from across the Caribbean islands. It ran for more than 40 years.

"It helped me to bring together the West Indian community and to a great extent, the indigenous population to better understand each other more," Afflick said.

Watch Afflick and Walker on their struggles and life in Preston

Black amateur cricketers and their struggles in Preston

'Every Christmas we speak to each other'

Enduring life-long friendships between West Indies players and team-mates included Jim Eland and Wes Hall, who opened the bowling together for Accrington 50 years ago.

Eland suffers from Alzheimers, but a mention of those tumbling wickets or a glimpse of an old photograph takes him back.

"Some days he might not remember how to switch the television on with the remote but the moment a cricketer's name is mentioned it all comes flooding back," Jim's wife Valerie said.

Eland visited his former team-mate in Barbados and Hall took him to Kensington Oval in Bridgetown, the island's international ground, where the West Indian great terrorised many an international batsman.

"I was so pleased to heartily reciprocate all the good things he had done for me," said Hall.

John Cook and Charlie Griffith also have a similar bond after their time together playing at Burnley.

"Every Christmas morning we speak to each other," Cook said.

"He usually tells me that it is a lovely morning and he is going to the beach to see his racehorses - whereas I am telling him it is either snowing or pouring with rain."

Watch West Indies great Hall describe his life-long friendship with Eland

My memories of Wes Hall

Viv Richards - fearsome, famous and freaky weather - the 1980s

Ever the showman, Viv Richards arrives at Rishton Cricket Club in style

In the 1980s Viv Richards was one of cricket's global superstars. He captained the all-conquering West Indies in 50 Tests without losing a series and smashed his way to 35 international centuries in all formats.

But in 1987 he signed for Rishton, a small village near Blackburn.

Richards made a typically flamboyant arrival, by helicopter, 30 minutes before the start of his debut.

"It was quite a spectacular landing," Richards said.

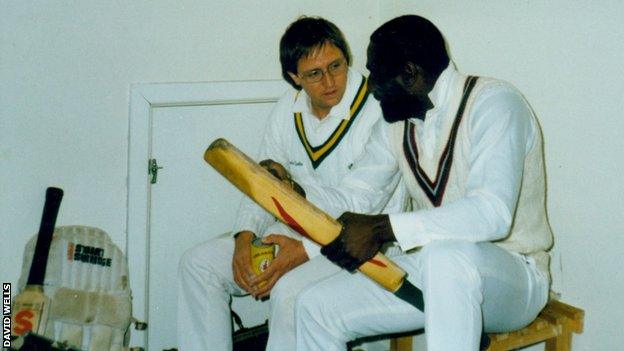

Viv Richards (right) said he "just clicked" with the his team-mates in the Rishton dressing room, including with captain David Wells (left)

Rishton captain David Wells added: "I was looking in the distance, seeing this little dot get bigger, and bigger and bigger until eventually this massive helicopter landed on the outfield here and the place erupted."

Richards' arrival reignited the heyday of the Lancashire League, but the all-rounder was not greeted by Caribbean sunshine.

"One of the things I remember more than anything else were the hailstones," Richards said. "I was saying 'is there going to be a cricket match here today'?"

But the game was played and Richards warmed the crowd up with 87 runs in a Rishton victory.

"Everyone is supposed to get their day in the sun and mine was 'saying I captained Viv Richards'," Wells said.

Watch: The crowds, the chopper, the star appeal - when Viv landed in Lancashire

Sir Viv Richards an honorary Lancastrian

'It was the 1980s but cricket was still segregated'

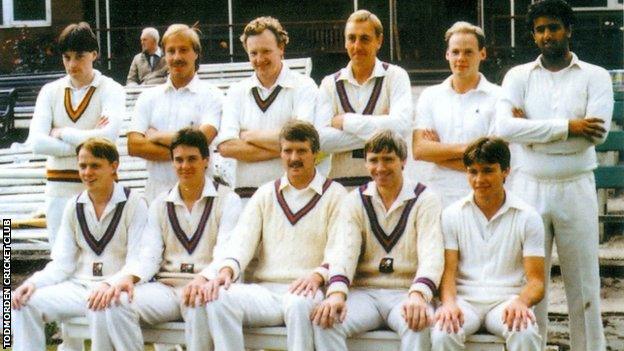

Ibrar Ali (back, right) says he was "made very welcome" when he joined Todmorden CC

West Indian players had become regulars in the league but, despite an influx of south Asian workers to the region's textile industry, the same was not the case for Asian cricketers.

Ibrar Ali played against Viv Richards for Todmorden, becoming one of the league's first Asian amateurs.

Cricket historian Brian Heywood said it took "quite a while" for the social cohesion to build through cricket.

"That's still developing and I think that could have happened faster," he added.

Biographer Jeff Hill explained: "I think the clubs were a bit slow on the uptake to be honest. There were plenty of examples where cricket was still segregated."

Ibrar was introduced to Todmorden by Malcolm Heywood, a headteacher at a local school, and still plays for the club 40 years later.

"I would stand here [at the club's gates] and watch because I didn't have the money to pay and go on," Ibrar said.

"I was absolutely sure it was what I wanted to do but I never had the courage to come on and speak to anyone.

"It has certainly changed in the past 10 or 15 years. Most teams we come across now have a number of Asians in any given team from juniors through to the first team."

Watch: How Ibrar blazed a trail for Asian cricketers in Lancashire

Asian influence in Lancashire cricket league

'2017 - the league's best days are behind it'

With the ever-increasing international schedules and the pull of Twenty20 leagues, the days of a world-class professional have passed.

Grounds where thousands once crammed through the gates are now the destination for only the dedicated.

"I don't think anybody would pretend it's the same as it was. You get a handful of people watching the games and the golden era of the great professional has gone," Lloyd says.

Crowds may be low, but cricket still has a crucial role to play.

In Nelson, which has the country's only remaining British National Party (BNP) councillor, current player Khurram Nazir says the town still has a "problem" with segregation but the club are helping communities to mix.

"I am sure we can be used as an example to show how we've helped integrate our society and our communities together just through one sport."

The Lancashire League may not see the likes of Constantine, Richards Hall and Griffiths again but the towns have left a lasting impact.

"I am only 80 and if there is one thing I am going to do is return to Accrington some time," Hall said.

And Richards, a self-proclaimed "honorary Lancastrian", has a similar appreciation for his East Lancashire home.

"Rishton sort of opened their arms," he said. "It's not just the memories of what you accomplish in county cricket, Test match cricket or world series cricket. That was something very special."

Watch: The golden era of the great professional has gone

Life in the Lancashire cricket League now

- Published30 September 2017