A sliding doors moment that consigned USA cricket to pub quiz answer

Listen to radio commentary on all 55 matches across BBC Sounds and the BBC Sport website and app, where live text and in-play video clips will be available on selected matches

- Published

The men's T20 World Cup is being hosted by the USA and West Indies, and kicks off on Sunday morning (01:30 BST). Here, BBC Sport looks back at the storied history of cricket in the USA.

It’s the question that has derailed many a pub quiz team over the years: which two nations contested the first international cricket match?

If you’ve ever fallen foul of it, you will probably remember it is not England and Australia, the countries that played the first Test matches, including the foundational encounter in 1882 at The Oval.

That game, won by Australia, led to the now famous ‘obituary’ for English cricket published in the Sporting Times, and the birth of the Ashes.

By then, a civil war had swept away the roots of the game in the place that had actually staged the first international: the United States of America.

It was there, on 24 September 1844 in New York, at a site that is now slap in the middle of Manhattan near the junction of First Avenue and East 31st Street, that the USA met Canada for what many regard as the first international encounter in any sport, pre-dating the America’s Cup yachting by almost seven years.

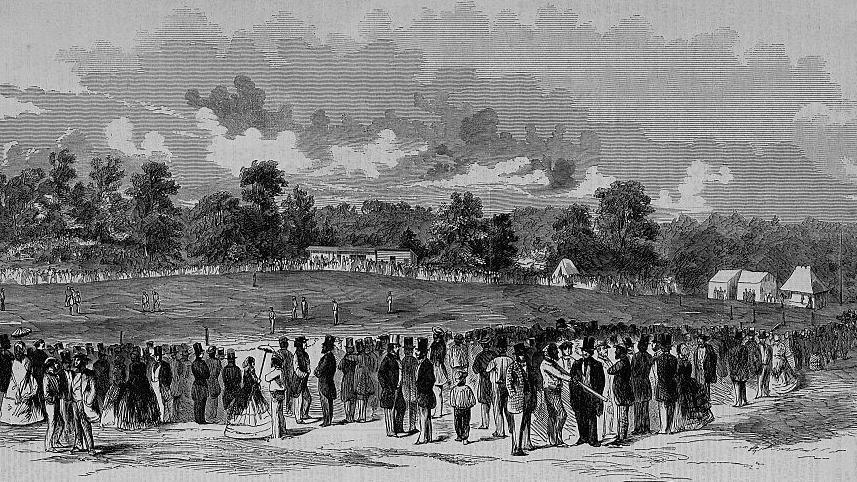

A postcard commemorating the 'Great Cricket Match' between the United States and Canada at Hoboken in New Jersey. The year is unknown

The contest was scheduled for two days, although rain meant that it ran into three.

Five thousand people attended the St George’s Club for the first day’s play, and over the course of the match, an estimated $100,000 (approximately $4.2m in today's money) was gambled on the outcome.

The Canadians, somewhat exhausted and bedraggled by a journey that had brought them up the St Lawrence River and across Lake Ontario by boat before catching trains to New York, batted first and made 82 against an US attack that consisted solely of two men born in Yorkshire: Sam Wright and Harry Groom.

Canada’s star was David Winckworth, who made 12 with the bat before sending down a few round-arm thunderbolts of his own, taking four wickets as the Americans were dismissed for 64.

Winckworth again top-scored with 14 as Canada stacked up another 63, setting the USA 82 to win.

The run chase began well, opening pair James Turner and John Syme making 25 without loss before the first international batting collapse took hold - George Sharpe carving through the next six wickets for just 11 runs, the Americans not helped by the mysterious absence of their number three, George Wheatcroft.

He appeared at the ground 20 minutes after the final wicket had fallen and began a heated row with the Canadians over whether the game should restart so that he could bat. Canada stood firm: they had won by 23 runs.

The fixture began a turbulent period of to-and-fro between the sides.

They met again home and away the following year, Canada winning both, before the USA took victory at a game in Harlem in 1846 amid such bad feeling that the fixture was not contested for another seven years.

Perhaps some of that was down to David Winckworth who, having starred for Canada in the first three matches, moved to Detroit and turned out for the USA in the 1846 game.

Coming to America

England's 12 'Champion Cricketers' on board a ship at Liverpool bound for America. Back row (from left to right): Carpenter, Caflyn, Lockyer, Wisden (seated), Stephenson, G Parr, Grundy, Cesar, Hayward and Jackson. Seated at front: Diver (left) and John Lillywhite

These matches and the men that played in them, now misty with time, suggest a kind of sliding doors moment, a chance for the sport of cricket to lay its roots down in the USA just as modernity was taking hold.

Brought over by the British, the game is mentioned in the diaries of the politician and planter William Bird III in 1704.

A version known as ‘wicket’ was widespread enough to count George Washington as a participant in at least one game according to the journal of a Valley Forge soldier called George Ewing.

It wrestled with baseball for popularity to the point that Professor Tim Lockley, a social historian of the American south at Warwick University, told the Guardian newspaper: “Cricket was by far the biggest sport in this period. Then the Civil War started in 1861, just when it was reaching its peak of popularity. The sport became a victim of that war”.

The sliding doors closed on cricket, at least as a mainstream sport.

After the Union victory in 1865, a handful of upmarket sporting clubs around New York and Philadelphia clung onto the game for a while.

Collegiate cricket flourished in the way that it did in England’s public schools.

The Philadelphian Club toured England in 1897 and played MCC, Oxford and Cambridge Universities and most of the county sides, their mighty all-rounder Bart King causing a stir as he destroyed a full-strength Sussex almost single-handed.

The team returned twice more, in 1903, when King inspired wins over Lancashire and Surrey, and 1908, when he topped the national bowling averages.

Once international cricket began to coalesce around the Imperial Cricket Conference, formed in 1909 by England, Australia and South Africa, America was sidelined.

The geography of cricket became the geography of empire: the Indian sub-continent, Australia, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, West Indies and South Africa all shared that dubious colonial root. In turn, their admissions to international cricket and subsequent first victories over the ‘mother country’ of England came freighted with meaning.

It was these diasporas that would offer a foothold to the game in America.

Dwight Eisenhower attended a game in Karachi. Donald Trump tried – and failed – to pronounce the names of Sachin Tendulkar and Virat Kohli during a visit to India.

Los Angeles was home to two clubs that gained a degree of fame: the Hollywood Cricket Club, which featured Boris Karloff - the man who portrayed Frankenstein's monster on the big screen - among its players, and the Compton Cricket Club, which used cricket to combat gang violence.

Perhaps the most significant contribution came online, from Simon King at the University of Minnesota, who, in 1993, began a proto-website that he named Cricinfo, ostensibly to test the possibilities of a new medium called the World Wide Web.

Cricket-obsessed students and researchers around the world began to contribute, and the site, now ESPNCricinfo, grew into one of the first and deepest online resources for any sport.

The future bites

Professional T20 cricket, a brainwave of the England and Wales Cricket Board's that began in 2003, is the accelerated format that 21st Century culture both demanded and embraces.

The Indian Premier League, the form’s ultimate iteration, is packed with globetrotting players and sprinkled with Bollywood stardust. Each of its 74 games are worth £10.5m, a figure that puts it behind only the NFL and the Premier League in per-match value.

It is this combination of format and profitability that America may find impossible to ignore.

Cricket has sought its tipping point since the USA’s admission as an associate member of the ICC in 1965, but its history has been one of mismanagement and maladministration. In the local vernacular, it has all been a bit small time.

Cricket and football, each with giant footprints in other parts of the globe, have found America hard to penetrate.

The US is large enough and populous enough to sustain an internalised culture, at least in terms of its most beloved sports of basketball, baseball and gridiron.

They prosper in America in a way that they do not elsewhere in the world. Cricket (and football) requires the USA to accept that it cannot dominate or win everything – at least for now – and that is a hard sell to the uncommitted.

Going Major League

In 2015, Sachin Tendulkar and Shane Warne were among the star names to play in a three-match series of All-Star games in New York, Houston and Los Angeles

2023 saw the most concerted effort so far to relaunch with the establishing of Major League Cricket, a franchise tournament on the IPL model that is building stadiums in six cities including Los Angeles, New York and Washington.

It has powerful investors with Indian-American roots, including Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and Adobe executive Shantanu Narayan.

The first season attracted white-ball names as big as England’s 50-over World Cup winner Jason Roy, West Indies big hitters Sunil Narine and Andre Russell and new Aussie sensation Jake Fraser-McGurk, alongside established IPL stars Nicholas Pooran, Glenn Maxwell, Trent Boult and Kagiso Rabada.

MLC will begin its second season just four days after the men’s T20 World Cup final.

That World Cup will see the United States and Canada compete with the big boys, and, in an echo of the sport’s origin story, they will contest the tournament’s opening fixture, at the Grand Prairie Stadium in Dallas on 1 June.

Florida and New York will join Texas in hosting matches for the five sides competing in Group A, including the biggest game of them all, India against Pakistan in New York on 9 June.

That encounter will hold the attention of the world and will be played in a temporary stadium that seats 34,000 – more than can attend any English Test match venue apart from Old Trafford.

Those kind of numbers continue to tantalise everyone that sees the sport having a real and profitable future across the Atlantic. In the end, like cricket itself, it’s a numbers game and America has always been keen on very big numbers.

Related topics

- Published29 June 2024

- Published14 July 2023