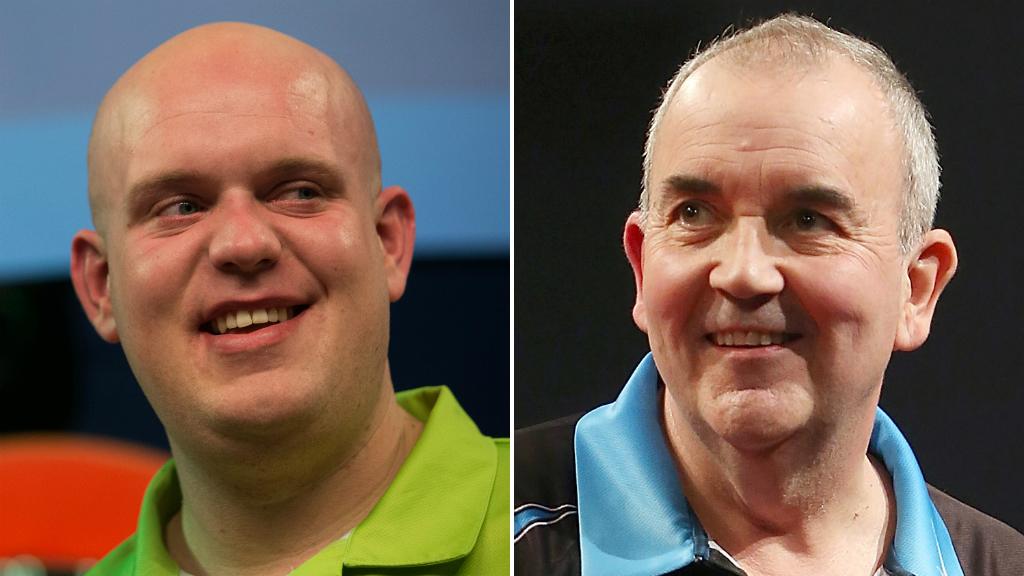

Phil Taylor: Darts says farewell to sport's unlikely revolutionary

- Published

- comments

Taylor won eight successive World Championships from 1995-2002

Phil Taylor might look an unlikely revolutionary: comfortable over-belt spread, preference for polo shirts, new-build detached home just outside Stoke. He is darts royalty, the face of its establishment and the guts of its popular appeal.

Neither do his 16 world titles appear to have changed him. As he retires from competitive arrows, he is still a Burslem boy in outlook and accent, in touch with his roots not least because they are still entwined around him.

It is the circumstances surrounding him that have altered beyond imagination. Taylor began his career in the fags-sponsored doldrums, when darts seemed to be going the same way as greyhound racing and speedway and other 1980s second-division sporting staples.

He ended it - with a 7-2 defeat to debutant Rob Cross in Monday's final - with the PDC World Championship like some unholy half-cut mix of seaside-town stag-do and hipster social tourism, Alexandra Palace heaving, £400,000 on offer to the winner and families at home interrupting festivities to watch on television.

Much of it shouldn't make sense. The big darts nights out have at their heart the strange paradox you are going to watch a sport you can't actually see when you're there.

Taylor won his first World Championship in 1990, beating his mentor Eric Bristow 6-1 in the final

Only perhaps during an evening session of a Test match in the Hollies Stand at Edgbaston or the Western Terrace at Headingley is so much drunk by so many people in such incongruous fancy dress. As someone once said about those cricket all-dayers, it's the genuine darts-loving Mother Superior you feel sorry for in all that mayhem.

It works, and it continues to grow, because of Taylor more than any other single actor.

He was not the only champion to split from the old British Darts Organisation in 1993; 16 of the world's top-ranked players did so. Neither was he the only player to put personal funds into the subsequent court battle between the BDO and what became the Professional Darts Corporation.

But it was his remarkable run of success - making every single world final from 1994 to 2007, winning eight consecutive world championships from 1995 to 2002 - that both legitimised and buttressed the breakaway, transforming the sport in the process from pub pastime to something that could make its stars millions. That was 'The Power' in action.

Phil Taylor's major titles | |

|---|---|

World Championship (16): 1990 (BDO), 1992 (BDO), 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2009, 2010, 2013 | |

World Matchplay (16): 1995, 1997, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2017 | |

World Grand Prix (11): 1998, 1999, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2013 | |

Grand Slam of Darts (6): 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2014 | |

UK Open (5): 2003, 2005, 2009, 2010, 2013 | |

European Championship (4): 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011 | |

Players' Championship Finals (3): 2009, 2011, 2012 |

"When I first started doing exhibitions, you'd have 20 people down the pub, if you were lucky," he told BBC Sport a few years ago.

"If we went to the US for a tournament, we'd have to get to the final just to get our money back. We'd go down the butchers and buy a loaf of bread, some butter, some boiled ham and some bags of crisps for dinner."

If it feels grandiose to compare what Taylor did for darts with the effect on football of Jimmy Hill's campaign to scrap football's maximum wage, or on cricket of Richie Benaud's support for Kerry Packer's World Series, it is only because of the condescension that sometimes surrounds his chosen sport.

If you took Taylor out of the past quarter-century of darts, there is a decent argument it would be as unrecognisable as cricket without limited-overs leagues, or English football without overseas stars on big salaries.

Of course, there were other great players through his era. But the old hegemony of Eric Bristow, John Lowe, Jocky Wilson and Bob Anderson was breaking up as he began to flourish, the influx of Dutch talent still years away.

There were rivalries, not least with Dennis Priestley, Raymond van Barneveld and John Part, but they were never close. Taylor beat Priestley in 37 of their 44 meetings, lost to Van Barneveld only 17 times in 77 and had a 31-6 win/loss record against Part.

Taylor claimed a record-extending 16th World Matchplay title in July, seeing off rivals Raymond van Barneveld, Michael van Gerwen, Adrian Lewis and Peter Wright

When Part beat Taylor in the epic world final of 2003, external it was more about Taylor's capitulation as 1-7 favourite than Part's triumph; when Van Barneveld beat him in a sudden-death leg in the 2007 final,, external it was a regicide as much as a coronation.

An unlikely revolutionary, but a logical one too. Taylor made it big in part because he had his background chasing at his heels. When you spend your early years living in the ground floor of your terraced house because the first floor has been condemned, it tends to put a kick in your pursuit of better.

Taylor's first job after school, aged 15, was as a dogsbody - his words - in a sheet-metal factory on a wage of £9 a week. When he started making toilet handles in a local ceramic factory it was considered a significant step up. To this day he has never taken out a mortgage, paying for each of his many properties in cash.

The success came with flaws. Some of the same darkness that has haunted his mentor Bristow is also present in the protege made superstar - convicted of indecent assault in 2001;, external his daughters Kelly and Natalie claiming in the Sun newspaper two years ago that they were living on benefits after he had cut contact with them; a costly divorce from their mother Yvonne that left him with legal rights to his nickname but poorer for five houses, his pension and a payment of £830,000.

Like Bristow, with whom he used to push himself through eight-hour practice marathons as the former five-time world champion tried to get over the dartitis that had wrecked his career, his dedication sometimes became an obsession.

"He made me into a winner," Taylor says of Bristow, now ostracised from the sport for inflammatory comments he made on social media last year. "I didn't know how to win before I met him."

Ruthless as a finisher of tight matches when at his peak, the one player who would make the killer double when it had to be made, Taylor played a match on his wedding day; the day after his mother died in Stoke, he was in Bournemouth to take part in a Premier League event.

At his peak he worked harder in practice sessions than any other player. In matches he was mentally impregnable. Everything he did was focused on the oche.

"If you told me I was at number 34 Blake Street, I'd immediately think 'double 17'," he once told sports writer Rob Smyth. "If I was at number 37, I'd think 'five, double 16'."

They will still serenade him with the old chorus of 'Walking in a Taylor Wonderland' at Ally Pally when he plays his final first-round match on Friday.

'Power' tattooed in red on his right arm, 'Glory' on the left. In his wake a sport transformed, even as he has stayed the same.

This feature was originally published on 14 December 2017, and amended on 1 January 2018.

- Published1 January 2018

- Published1 January 2018

- Published13 December 2017

- Published27 November 2017

- Attribution

- Published29 November 2017