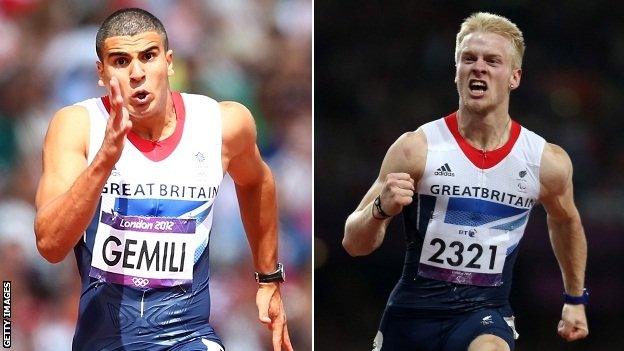

Jonnie Peacock and Adam Gemili are going places fast

- Published

When I suggest to Adam Gemili that he and fellow teenager Jonnie Peacock are on similar career paths, Gemili, a little embarrassed, points out that while he failed to reach the 100m final at the Olympics, blade-runner Peacock won gold at the Paralympics. This was, as teenagers are wont to say nowadays, my bad.

For I had forgotten what Gemili had not, namely that this was the summer when Paralympic performances ceased to be, to use that horribly condescending word, worthy but rather commensurate to performances by able-bodied athletes.

"Jonnie trains at Lea Valley, where I train, and I see the work he puts in," Gemili, 18, tells BBC Sport. "It's twice as hard for Paralympians. Most people in Jonnie's situation would have given up but he didn't. Now he's a Paralympic champion."

Peacock, 19, holds the distinction of being the only athlete, Olympic or Paralympic, to have his name chanted by the crowd in the Olympic Stadium. So delirious were they before his T44 100m final that he had to shush them to quieten them down.

Gemili targets 2016 medal

"That was a bit weird, but it was great fun," says world record-holder Peacock. "Hopefully, people view the Paralympics differently now. People weren't looking at it and thinking, 'bloody hell, these blokes have got no legs,' they were thinking, 'bloody hell, that was a close race, that was tense.' That was amazing to hear.

"I used to feel patronised but this Paralympics has changed people's perceptions and views. We're no longer felt sorry for, people aren't trying to dig for the back story.

"I've done one or two interviews about what happened to me when I was younger but everyone else is asking me about now. We're heading in the right direction."

Where Gemili is heading is more difficult to ascertain. "Hopefully, we're not going to have another broken junior," is Peacock's wry assessment, the Cambridge athlete being acutely aware that global success as a teenager rarely translates as emphatically to the senior ranks,, external at least as far as British sprinters are concerned.

Christian Malcolm, who won 100m and 200m gold at the World Juniors Championships in 1998, and Mark Lewis-Francis, who won 100m world junior gold in 2000, are two British juniors who never reached the same heights in the big boys' league. The injury-prone Harry Aikines-Aryeetey, who won 100m world junior gold in 2006, is currently discovering exactly how turbulent the transition can be.

"The potential has always been there but maybe in the past the progression into the seniors was rushed and not done right," says Gemili, a former Chelsea youth player who only took up athletics training full-time in January of this year.

"Christian, Mark and Harry were all at the Olympics, I spoke to them about what did and didn't go right and hopefully I'll learn from it. I don't want to be peaking at 18."

Heartening amputee text touches Jonnie Peacock

Gemili has already gone quicker over 100m than Malcolm and Aikines-Aryeetey, while his personal best of 10.05 seconds is only 0.01secs slower than the best time of Lewis-Francis, set when the Midlands athlete was only 19.

Almost as scary as Gemili's precocious talent is that he could have still been playing football in the lower reaches of the English leagues, having been on loan at Thurrock from Dagenham and Redbridge, external when he made the decision to fully commit to athletics.

"Different coaches spotted me at the Kent and then the English Schools Championships and asked me to come and train with them," says Gemili, who was running 10.2 seconds fuelled by natural talent alone. "But I just thought, 'I'm a footballer, that's what I am.'"

It was only when Gemili, of Moroccan-Iranian descent - "it's a very weird background for a sprinter, but it's working for me" - won silver at the European Junior Championships in 2011 that he thought he might actually be an athlete after all.

"It really does scare me, that I could have been missed," says Gemili. "A lot of the guys I was with at Chelsea were so reliant on it. Some of them dropped out of school, some of them thought they had made it and they didn't. They're stuck with no education, they're trying to get a job, it's hard to see them struggling.

"Having said that, I only thought I could really go places in athletics when I won the World Junior Championships in Barcelona in July. I just thought, 'Hmmm, I've just run one of the quickest times for a junior. Let's do this.'"

Peacock, meanwhile, has already done it. The world record-holder in his event with a time of 10.85secs and the man whose 100m final was watched by 6.3m television viewers is the beneficiary of a more informed age and enlightened parenting. In particular, having a mum who never let him off doing the washing-up, despite missing a leg.

"If I told her I didn't want to do the washing-up because I didn't have my artificial leg on, she'd pull up a chair and say, 'Kneel on that and do it,'" says Peacock, whose right leg was amputated below the knee after he contracted meningitis at the age of five.

"What I would say to parents in a similar situation is that you shouldn't view your child as different or try to give them the special treatment. Don't change anything but keep pushing for them like you would anyone else."

When I ask Peacock what I think might be a slightly inappropriate question, namely would he trade his gold medal for a fully-functioning leg, he is unequivocal. "I'd definitely stay the same," he says.

"Maybe if you said, 'Jonnie, you can have your leg back in 20 years' time, when your back starts to ache,' I'd make the swap. But at the moment I'm loving life. I wouldn't change a thing."

And so it is Gemili still with everything to prove and Peacock striving to stay on top. Two British teenage sprint sensations sharing the headlines, two products of a summer of sport which demonstrated that a disability is not necessarily a disability at all.