Rio 2016: Paralympics GB judoka Jono Drane rebuilds mind & body

- Published

How GB judoka Drane made team for Rio Paralympics

You are in your twenties and your life is stretched out before you. Seemingly unopposed. Growing pains behind you, successful business grown from scratch. And suddenly it all comes crashing down around you.

Norwich judoka Jono Drane got a second chance and realised a second dream. And down it came again. Mental wounds grew upon physical wounds and life was brimming with hurdles to be hacked through, all over again.

But the 29-year-old will be in Rio for this summer's Paralympics. Visually-impaired, slightly suspect knee, grappling anxiety and depression. Still hacking, but at least there is a tangible reward within reach.

'Horrible and unfair'

Having built up a plumbing and heating business, Drane went for a routine eye-check in 2011, when he was told he had the progressive eye condition corneal dystrophy.

"I'd always had problems with my eyesight - problems with astigmatism [blurred vision] - things like that," he recalls. "But I just remember being told after the tests that I wasn't allowed to drive home.

"Then a load of things made sense - for example, I'd had a fall-out with friends because they hadn't helped me when I had asked for driving instructions. It's progressive and you don't notice - it's not like one day you wake up and you can't see. You just accept it for what it is.

"It was horrible having to shut down your own business. I put so much energy into this one thing and then it just seemed very unfair that it just disappeared."

Saved by judo?

Judo had been a part of Drane's life since his teenage years. Diagnosed with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) , externalat 15, he used it as a way of channelling his energies during what was a difficult time.

The sport joined the Paralympics in 1988. Exclusively for athletes with vision problems, it differs from the sighted sport in that fighters grip up at the start and commands are given verbally.

It seemed like a perfect match for Drane, given the talent he already had. But he was reluctant to go down that road, having already had something he had worked hard for taken away from him in an instant.

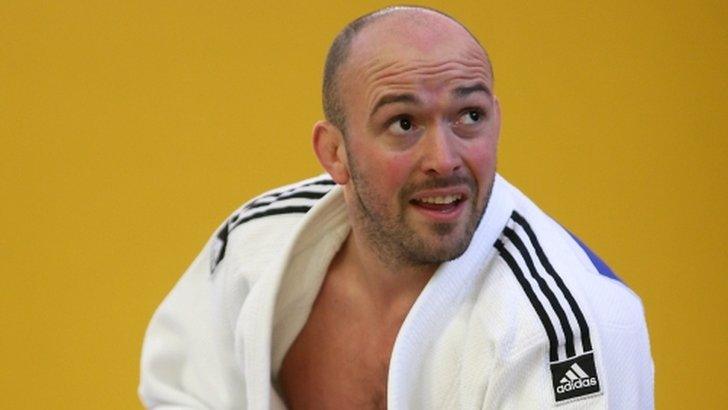

Drane will be hoping to use his power on the judo mat in Rio in September

At the 2012 London Paralympics, he acted as a training partner for some of the GB team. Perversely, and much to his frustration, his vision was not good enough for him to drive a car but was too good for him to be part of the official training squad.

But his eyesight continued to deteriorate and eventually, when it got bad enough to make him eligible for competition, Drane agreed to give visually-impaired judo a chance.

In 2013, Drane joined the full-time GB programme based in Walsall. He was fifth at the European Championships that year before winning bronze at the 2014 World Championships. Not bad for a relative beginner. But stand by for another cruel blow.

'A sad place'

Drane was already receiving treatment for depression and anxiety when he suffered a cruciate knee ligament injury last year, 17 months before the Rio Paralympics.

"I don't think the injury helped my state of mind. It got quite severe and I don't think I dealt with it very well," says Drane, whose coach Ian Johns was an unfailing support.

"I was in a very sad place and everything seemed so unfair. So the first four months of my rehabilitation were about rehabilitating my mind, getting my head straight and trying to work out what is important to me and what isn't.

"It went as far as depression can go and I am very fortunate that the British Athletes Commission got me good help on the mental health side of things, which wouldn't have been available had I not been an athlete. I am very lucky."

Having already been a passionate advocate for ADHD and become a patron of the ADHD Foundation, Drane is now hoping that speaking out about his experience with depression can help others in the same situation. But dealing with his own medical conditions remains an ongoing challenge.

"I don't think the ADHD is a particularly great partner for my sight loss," he says. "There is just such a short distance between impulse and action that it becomes very stressful.

"You become concerned about what person you are when you wake up - if you are going to be able to do a task that you did very well yesterday or not at all.

"It is very hard to have confidence in what you are going to do because I don't know who is going to turn up and what attention level I am going to have.

"I take medication every morning but I don't think being reliant on it is a good thing. However, I live in fear of a life without that medication and I don't know who I am."

Rio on the horizon

Drane says he is happy at the moment. The knee has healed well and he travels to Rio this month for a training camp and competition. In June, he will be in action in front of a home crowd in the International Blind Sports Grand Prix in Walsall.

So, given everything that has gone wrong, can he allow himself to think about winning a medal in Rio?

"I am competitive but I know it isn't too healthy for me to think about it," he says. "At the moment it is about just keeping things simple and looking after myself."

GB's judo squad for the Rio Paralympics is Sam Ingram, Jono Drane, Chris Skelley and Jack Hodgson (left to right)

"Paralympic judo over the last six years has progressively got so much harder, so to win a medal has never been as difficult as it is now. I don't see any reason why I can't win but there are plenty of reasons why I can't win.

"You can do all the preparation in the world get it right but sometimes the medal just doesn't go to the right person on the day. That is what makes sport so brilliant."

- Published23 August 2016

- Published11 February 2016

- Published12 May 2015

- Published5 September 2016