Marieke Vervoort: Tribute to the Paralympian, who ended her life through euthanasia

- Published

Living with euthanasia: Marieke's story

When I heard Marieke Vervoort had died, I felt deeply sad - for her loving family, her many friends and her fans around the world.

She was a remarkable champion, on and off the track. She was outrageously funny and full of life, but I've never had such frank conversations about death with anyone.

Somehow, though, those conversations weren't depressing; she had accepted her time on earth would be shorter than many, but she was determined to wring every last drop of fun out of it that she could.

I can still hear her voice telling us to enjoy "every little moment". And she had planned her end.

"I want to end like Marieke", she told me, a year on from our first visit, when her eyesight was failing and she was increasingly dependent on carers and medics to alleviate her constant pain.

We drank cava on a beautiful summer's evening; she was still able to enjoy the good moments, but they were becoming less frequent.

Her friend Lieve told us then she thought she might have another six months, maybe a year. That was two years ago.

I hope and pray that, when the end came, it was a soft and beautiful death, as she wished.

I'll never forget her, or the two extraordinary days we shared with her, talking about how to die and, crucially, how to live.

A version of the article below was originally published in December 2016. It has been updated by the author following the death of Marieke Vervoort.

Doors open for you in Diest when you're with Marieke Vervoort.

Go to a restaurant in this pretty Belgian town, and all the diners know her. They come over to congratulate her on winning two medals at the 2016 Rio Paralympics; she raises a glass to a family celebrating a birthday.

For a few hours, she's the life and soul of the party.

But, at 37, the Belgian wheelchair racer suffers such pain she wakes her neighbours by screaming in the night. As she watches her precious, fiercely defended independence dwindling, she has planned her own death.

Euthanasia is legal in Belgium, and in 2008 Vervoort signed the papers which will, eventually, allow a doctor to end her life. It's not that she wants to die. She wants to live. But she wants to live on her terms.

'My mind says yes, but my body cries'

It is three months since she won silver and bronze at her second Paralympics [at Rio 2016] and Vervoort is still the toast of Diest, where a large billboard bearing an image of her face declares the town is "so proud" of her.

We're greeted at the door of her specially adapted flat by Zenn, Vervoort's assistance labrador. Nurses come in four times a day to tend to Vervoort's medical needs, but Zenn gives her mistress an extra degree of independence, fetching items and helping her dress. She is, most of all, a mood-enhancer.

'Zenn makes me Zen,' says Vervoort

"When I'm happy, she's happy," says Vervoort. "When I'm mad, she's scared, and she goes to sit in another part of the house so she's not bothering me. When I'm crying, she'll come to lie down with me, lick my face, hug me.

"When I'm going to have an epileptic attack, she pushes her head between my knees. She is saying to me, 'Marieke, you have to lay down. Go to a safe spot because something is going to happen to you'."

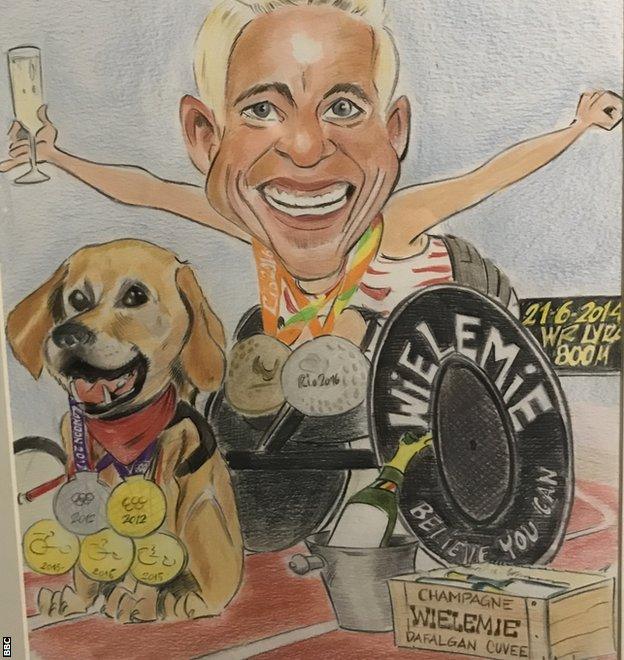

The walls of her flat are crammed with framed photos and paintings of her winning moments, while medals, trophies, and bottles of champagne jostle for space on cupboards and counter tops.

Her achievements have been hard won. A progressive, incurable spinal condition, diagnosed when she was 21, ravages her body and no two days are the same.

"I know how I feel now, but I don't know how I'll feel after half an hour," she says. "It can be that I feel very, very bad, I get an epileptic attack, I cry, I scream because of pain. I need a lot of painkillers, valium, morphine.

"A lot of people ask me how is it possible that you can have such good results and still be smiling with all the pain and medication that eats your muscles. For me, sports, and racing with a wheelchair - it's a kind of medication."

Just getting to the start line in Rio was an achievement. In 2013, a racing accident left her shoulder so badly damaged a doctor told her she would never reach the top again. To that, as to so many setbacks in life, her response was a defiant hand gesture.

"I turned my bed into a gym - physio, elastic belts," she says.

"I was doing my own physio, my own exercises. After the rehabilitation, I broke three world records."

She went back to her doctor and thanked her for telling her she would not reach the top again.

"You gave me the power to fight back like an animal," she told her doctor. "You make my mind only stronger."

Vervoort was happy to end her career on a high but sad to say goodbye to the sport she loves

The silver medal in the T52 400m in Rio came after 30 hours of violent sickness and a day on a rehydrating drip in the Paralympic village. The bronze in the 100m came after a bladder infection sent her temperature soaring.

She said they were medals with two sides - happy and sad.

"I can't imagine a better way to end your career, but also there's a side of sadness, to say goodbye to the sports that I love," she explains.

"Other people stop with their sports because they say they don't want to do it any more. I have to stop because my mind says yes, go further, you still can do it. But my body cries, says help, stop training, you break me."

Marieke's major medals | |

|---|---|

2012 Paralympics: Gold (T52 100m) and silver (T52 200m) | |

2015 World Championships: Gold (T52 100m, 200m and 400m) | |

2016 Paralympics: Silver (T51/52 400m) and bronze (T51/52 100m) |

'A living hell is not the life that she wants'

To get a fuller picture of the athlete known as 'The Beast from Diest', we travel to see her close friend Lieve Bullens, the woman Vervoort calls her "Godmother".

Ask Vervoort's friends and family to describe her and they will use a variety of adjectives. Determined, independent, joyful, stubborn. I would add funny, thoughtful and a terrible back-seat driver.

The constant threat of an epileptic episode and her deteriorating sight mean she is no longer allowed to drive her car, emblazoned with her picture, fist punching the air after another race win. I take the wheel. It's clear my caution is damaging her image as Belgium's fastest woman on three wheels.

"You are driving like an old woman! Ha ha ha!"

Many pictures on her walls celebrate the achievements of Vervoort, whose nickname is Wielemie

Bullens welcomes us into a house which is part home, part Buddhist retreat. Large windows overlook the winter garden, drums and dreamcatchers are suspended from the ceiling. The open cooking range has been converted into a candle-laden altar. It's the perfect place to recuperate from the stress of the car journey.

Vervoort met Bullens, a mental coach and therapist, when competing at the 2007 Hawaii Ironman triathlon for para-athletes.

Triathlon had become her passion when the onset of her disease made her reliant on a wheelchair. She was para-triathlon world champion twice, but in 2008 her condition deteriorated to such an extent she had to give up the sport.

It was the lowest point in her life. The pain was agonising, the loss of independence insupportable. She told her friend she wanted to kill herself.

"She said 'there's no point in living, no point in going on because it's too hard, it's too bad'," Bullens says.

But Vervoort's psychologist recommended she speak to Dr Wim Distelmans, a leading palliative care expert. He suggested an alternative option: euthanasia.

Euthanasia - in which a doctor intervenes to end a life - has been legal in Belgium since 2002. It is available only if a patient has an incurable condition, is in unbearable pain, and is able to make a rational decision to request it, and even then two doctors have to agree it is the correct course of action.

In 2015, MPs in the UK rejected the Assisted Dying Bill, which would have allowed some terminally ill adults to end their lives with medical supervision.

Bullens was the first person Vervoort told about her decision. She is also the person she wants with her when she dies.

"I immediately supported her," Bullens says. "She is stubborn. She knows what she wants. But she also knows what she doesn't want. A living hell is not the life that she wants.

"I immediately had the feeling it was something that she could control, and if she had control of her life, she would live longer. The pain is always there. She doesn't have to wait for the pain to have an end for her life. She says to the pain - I decide when to go. Not you."

In the hall of Bullens' house is a wall upon which friends and guests have written inspirational messages. But, until now, not Vervoort. She puts that right. It's a painful process, as her hands are beginning to fail her. Bullens knows it's a precious moment.

"The woman who's writing it is forever in my heart," she says. "She's not forever physically. It's a peaceful thought that she will go in a beautiful way, and not a hard way. In a strong way."

What is the law in Belgium? | |

|---|---|

Belgium, like the Netherlands and Luxembourg, permits euthanasia | |

A patient's suffering must be constant, unbearable and the illness must be serious and incurable | |

Since 2014, a terminally ill child in Belgium may also request euthanasia with parental consent but extra assessment is required | |

An adult does not have to be terminally ill but must be mentally competent | |

A child seeking euthanasia must be terminally ill, external and mentally competent |

'I'm a real rich girl, even with this miserable, ugly disease'

Jos and Odette Vervoort are no different to many proud sporting parents, travelling extensively to support their daughter. They get out a photo album of memorable moments on Copacabana Beach, Sugarloaf Mountain, and - the highlight - Vervoort being presented with her silver medal and getting a hug from Princess Astrid of Belgium.

They've watched their sporty child grow into a world-beating adult. Like all parents, they know they need to let their child go. But for them, letting go means having to support her decision to end her life with euthanasia.

"She's always been independent," Jos says. "When she came in a wheelchair, she was frightened she would live all her life as a disabled person with mum and dad under the same roof.

"You can see her situation, you are realistic, and you say yes, if she feels better with [the decision to choose euthanasia], I can live with it.

"In the beginning we knew it was a decision for the future. Now we know the future is coming near.

"It may be a question of months, a question of years. But we see as she becomes more dependent, it becomes more difficult."

Her parents don't know, and she doesn't know, when the moment will come. What is clear is she is not ready for it yet.

Vervoort has swapped wheels for wings

She has given up wheelchair racing and taken up indoor sky diving - the vertical wind tunnel allows her battered body a sense of precious freedom - with the aim of doing an unassisted dive from a plane.

She wants to fly in a stunt plane, and bungee jump from a bridge. She loathes not being able to drive her car, but her friends, family and Zenn give her much to live for.

"I'm the richest girl in the world," she says.

"I'm a real rich girl, a really lucky person, even with this miserable, ugly disease which I hate."

Is she afraid of dying?

"No, if you asked me 10 years ago, do you want to do a bungee jump - are you crazy? I'm not afraid any more. I risk everything, and I love it, to do all these things, because I'm not afraid to die any more," she says.

"To me, death is peaceful, something that gives me a good feeling."

'I was thinking about how I was going to kill myself'

Vervoort's fridge is well stocked. Not with food on the day we're there, but with sparkling wine. She opens a bottle before dinner. It's part of her pain relief.

We go to eat with her at a restaurant in Diest, where she is the guest of honour. She recommends the sizzling beef and the shrimp tagliatelle, both delicious. It's a great night.

The next day we arrive to do one last interview but find Vervoort curled up on the couch, exhausted and barely conscious after a pain-racked night.

She called the nurses in the early hours to administer morphine. Zenn keeps close to her mistress' side.

It's hard to believe this is the irrepressible woman we spent the previous day with, and a stark reminder of how unpredictable her illness is.

But 40 minutes later, she wants to talk again. We talk about the reason she chose euthanasia over suicide.

"If I didn't have those papers, I wouldn't have been able to go into the Paralympics. I was a very depressed person - I was thinking about how I was going to kill myself," she explains.

"In England, I hope, and every country, they will look at euthanasia in another way - it's not murder. I'm the best example. It's thanks to those papers that I'm still living.

"All those people who get those papers here in Belgium - they have a good feeling. They don't have to die in pain. They can choose a moment, and be with the people they want to be with. With euthanasia you're sure that you will have a soft, beautiful death."

The conversation finishes in gales of laughter when Zenn, sensing the mood, decides to lighten it by passing wind.

Seconds later, Vervoort's eyes roll backwards. She's having an epileptic fit. We hit the red button and medical staff are there within a minute. It's become part of her life.

A couple of hours later she is in Brussels, giving a motivational speech and saying yes to selfies and autographs for anyone who wants them.

She is determined not to waste a second of the life she has remaining. She has planned her funeral, and it involves a lot of sparkling wine. She also knows what she wants her eulogy to say.

"I prepared everything. I wrote to every person who's in my heart. I wrote to every person a letter when I could still do it with my hands," she says.

"I wrote texts that they have to read. I want that everybody takes a glass of cava, [and toasts me] because she had a really good life. She had a really bad disease, but thanks to that disease, she was able to do things that people can only dream about, because I was mentally so strong.

"I want people to remember that Marieke was somebody living day by day and enjoying every little moment."

- Attribution

- Published12 September 2016

- Published19 September 2016