Oksana Masters: Paralympic champion on Chernobyl, Tokyo 2020 and upbringing in Ukraine

- Published

- comments

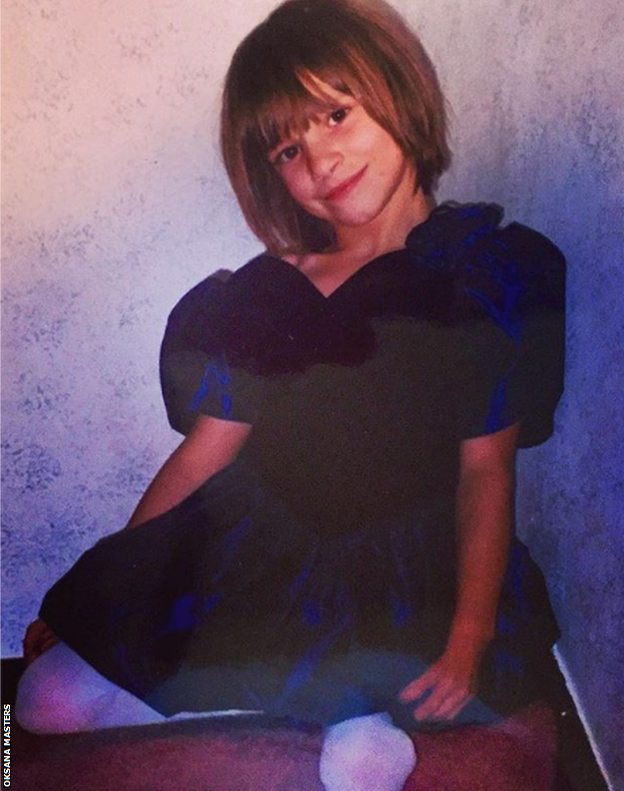

Masters was born three years after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster

Standing on a podium by Russia's Black Sea coast, Oksana Masters felt a surge of pride as the anthems played. It wasn't her first Paralympic medal, but this one was extra special.

She had just won cross country skiing silver at the Sochi Winter Games of 2014. As she held her prize, the flag of neighbouring Ukraine was raised for the winner, Lyudmila Pavlenko. Masters was herself born in Ukraine in 1989, three years after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster., external She was born with severe physical defects caused by exposure to radiation.

In Sochi she was competing for the USA, the country where she grew up, an adopted child raised by a single mother. Returning to somewhere so close to the country of her birth had been a big motivation for qualifying to compete in Russia.

"It was kind of coming full circle," she says. "It wasn't my gold-medal moment, but it sure felt like it."

Oksana's moment would come. Four years later, two of the five medals she won at Pyeongchang 2018 were gold. And this year she will be competing on the Paralympic stage for a fifth time - at the summer Games of Tokyo 2020.

It will be another chapter in the remarkable life story Oksana shared with BBC World Service. A story that begins in the Ukrainian orphanage that was her home until the age of seven.

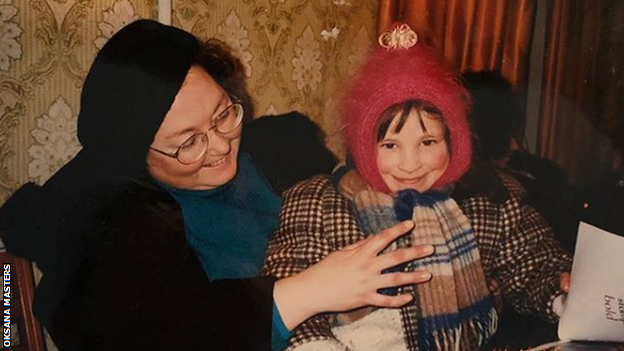

Masters says she and her mother "faced many unknowns together"

I have good and bad memories. I remember fields of sunflowers. I don't know if it was because I was tiny but they seemed massive. There was also a plum tree and we didn't get a lot of food so we would steal plums and pick seeds off the sunflowers.

Whenever I see sunflowers now, it's a good memory because what you read about eastern European orphanages is pretty accurate. I definitely remember the really, really sharp pain in your stomach from being hungry all the time.

Right from birth I was put up for adoption. I was born with six toes, I was missing the main weight-bearing bones in my legs, my knees were floating - they weren't supported by anything. My hands were webbed; I was born with five fingers, without thumbs. I don't have a right bicep, I'm missing some organs. I have one kidney and don't have any enamel on my teeth. When I came to America I found out that the only thing that can strip enamel before birth is radiation.

They linked it to Chernobyl because I was really not that far from there, and the fact that radiation levels continued to rise years after the explosion. It definitely lingered on years later to when I was born. There was also a power plant in the village of the orphanage that would go off frequently. Whenever the radiation was high there was this one cop who would drive round and tell us to board up the windows and doors, not to go out.

I've just finished watching the TV series Chernobyl. I knew parts of it. I knew that things went on behind the scenes to cover up the magnitude of it. It's sad that it took away so many lives and homes. That part of the country will never be the same.

I don't want to say I was a product of it but, out of something horrific, it's about how you can see the potential and possibilities - like becoming an athlete - instead of dwelling on it.

Masters has grown up to compete at four Paralympics - with Tokyo 2020 set to be her fifth

When I was five I was called into the director's office and they said: "We have a picture to show you - this is going to be your new mum." When I saw her face, she had the warmest eyes and warmest smile.

She'd never met me. She made her adoption choice on a picture of me. Every day until she came to the orphanage I would ask the director: "Can I look at my mum?"

Sometimes, if I wasn't good - because I was a troublemaker - then the director would use it against me and be like: "You can't look at the picture today. You're a bad girl. This is why she's not coming, because you don't listen." Because the process took two years I started to believe that. But her picture kept me going.

She fought for me for two years, and then she came and saw the situation I was living in. When she walked in the hallway there were people chipping away at the ice on the floor because the radiators had frozen.

Masters' adoptive mother, a professor at the University at Buffalo in New York state, knew that her daughter's left leg would have to be amputated. She had the operation at the age of nine, after moving to the US. In 2001, Masters' mother moved the family after taking a new position at the University of Louisville, Kentucky. A year later Masters became a double amputee.

In an Instagram caption to this picture, Masters wrote: "Mom, no words will ever come close to describe how much I love you and how amazing you are. I cherish this picture of us so much and your smile is all I need to feel complete and loved."

I didn't know I was different until I came to America. It was only then I realised that everything I had experienced was not normal.

I was diagnosed with 'failure to thrive' - basically starving to death. When I turned eight, I was 34 inches tall and weighed 36 pounds - that's a pretty healthy three-year-old here in the US! I had to wear toddler-sized clothes for my first couple of years.

Now that we're older and we can talk about her experience, I respect how hard it was for my mum. It was nearly impossible for a single parent to adopt. She had to do multiple psychiatric tests, with people asking 'why are you single? What's wrong with you? Where's your husband?'

I didn't realise all the struggles that go into adoption. I can't imagine how she faced that before she came across and met me for the first time. It shows her strength and her pure heart. Any parent who adopts kids is a pure gift but my mum doing it on her own is on a whole new level.

She knew my left leg had to go - it was six or seven inches shorter - so it was amputated when I was nine. That was hard but it was harder when I was 13 and the doctors told me they couldn't save my right leg.

For the longest time, I wasn't ready, because I knew what I was missing after the first amputation. I knew how limited things became for me. But the pain in my right leg had become unbearable and I said 'OK, I'm ready, under one condition - I can keep my knee'.

A lot of people don't realise that amputees aren't all the same. Your leg has an ankle and knee - two joints - so I didn't want to be missing four joints.

They said that was OK but right before I went on the operating table they said 'we're going to amputate above the knee'. I was so sedated I didn't know what was going on, but I will never forget that feeling of waking up in hospital. I tried to get up but didn't have that leverage from my legs anymore and fell backwards. That was really hard. Honestly, I still have a bit of frustration and anger about that.

In the end, it was to avoid having more surgeries down the line but it was weird because I didn't get a chance to say goodbye to that leg because I didn't know I'd be missing all of it.

Oksana also had multiple surgeries to both hands and began adaptive rowing in 2002. She would go on to win Paralympic bronze in 2012 - her first medal - partnering Rob Jones in the mixed double sculls. For Sochi 2014, she switched to cross country skiing.

Masters celebrates her first Paraylmpic gold medal at the 2018 Winter Games - she won both the 1.5km sprint classic sitting and 5km sitting events in cross country skiing

The first person that mentioned the Paralympics and racing internationally was Randy Mills [Louisville adaptive rowing club's programme director]. I'm so competitive, I hate to lose, and he saw that. All I needed was that fitness guidance to get to the next level.

I looked up the Paralympics in 2008 and I was like: 'Oh my gosh, this is so cool!' I didn't have a visual of someone that is like me, missing both legs, but racing for the USA at a high level. It took until London 2012 for me to realise: 'I belong here.' Then I dedicated everything to it.

Before those Games, Masters posed nude for ESPN's Body Issue.

I struggled a lot with my self-confidence as a girl. It's the end of the world if you're having a bad hair day or you have a pimple on your face for school picture day, let alone if you have prosthetic legs and hands that are hard to cover up.

Masters will be completing in the cycling events at the Tokyo Paralympics this summer

Then society has put this label on you, even though you don't see yourself as 'disabled'. That's something that's put on you.

I don't want the next generation of young girls and kids to grow up not having that person to look up to and want to aspire to. Every kid had a picture of Michael Jordan on their wall. Why can't it be a normal thing for that to be someone who has had an accident or was born with a disability? I don't want to say that because it's not a 'disability'. That's just a term society as a whole has put over everybody that looks different.

I believe that seeing is believing and the more times you see the Paralympics or a Para-athlete, the more normal it's going to become to the person that doesn't know what it is. It's really cool to watch that growth.

Masters won a bronze and silver medal at Sochi 2014 - both in cross country skiing. Four years later at Pyeongchang 2018 she won her first gold. At those Games, she and her partner Aaron Pike became four-time Paralympians. Now, Masters has reverted to cycling for Tokyo 2020, having just missed out on a medal at Rio 2016.

Aaron's such a patient person. I don't know how anyone can deal with my chaos. We started skiing together at the same time and spend the whole winter together so we push each other in training.

He'll get me on the downhills but I'm like 'haha, see ya' on the uphills because I climb faster than him. We can't switch off the competitive switch. If we play Monopoly and you're winning, it's not going to be a good experience for you!

But having someone like Aaron there is great on the training days when you're finding every excuse to not want to be there. You look over and it's your best friend, your partner, your team-mate. He's not just a great boyfriend. He has the same amount of genuine want for other people to do well and shares it with the team.

At Tokyo, the main goal is to win both of my events in the road race and time trial. In Rio I had limited time to really prepare because I was still spending my season nordic skiing and I transitioned within a few months.

I definitely have unfinished business going into Tokyo.