Amy Conroy: GB wheelchair basketball player drawing on experience to get through lockdown

- Published

Amy Conroy won World Championship silver with GB in 2018

"When life can be tough, we all have the ability to be tough right back and I do believe that good can come from hard times."

Just 20 minutes in Amy Conroy's company, even on the phone, is time well spent. In a time when the world needs a little positivity, she has it in abundance.

The emotions that so many of us are feeling right now - of helplessness, of a lack of control - are all too familiar to the GB wheelchair basketball player.

On her seventh birthday, she lost her mum to breast cancer. Five years later, Conroy was in hospital herself, having been diagnosed with osteosarcoma - bone cancer.

"Around the age of 12, I started getting this pain in my knee," the two-time Paralympian, now 27, tells BBC Sport. "The doctors said it was a sprain, or growing pains, or flat feet.

"The pain became worse over the course of about a year. It got too swollen to bend and I started collapsing around school. One time I couldn't get back up, I had to crawl to the nearest building in front of the boy I fancied, which wasn't ideal.

"I went to A&E the next day with my dad. It was when the doctor said that it was cancer that my world caved.

"At the time, cancer meant death to me. My grandparents, my uncle and my mum had died from it so I was instantly scared and thought this is it, I'm going to die at 13."

Conroy was given a 50% chance of survival, and at times it was "touch and go". She later had her left leg amputated as the cancer spread.

Chemotherapy was brutal. On her first day of treatment, she was sick 75 times.

"I don't know why I counted, I soon stopped that," says Conroy, who benefits from the Women's Sport Trust's 'Unlocked' campaign.

"I was fed through tubes, I couldn't really leave my bed because I would get sick, and I had many a bedpan mishap.

"My hair fell out and that was the only time I have ever had nits - kick a girl while she's down."

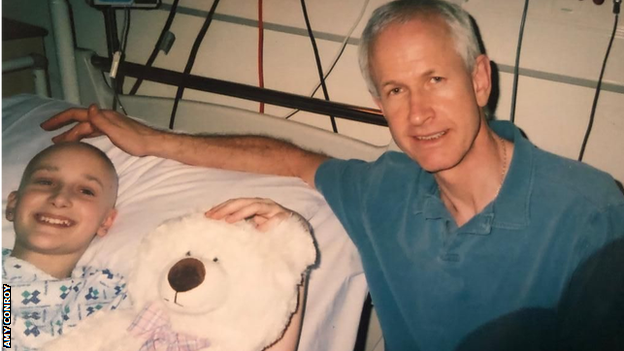

Conroy says her dad Chris "was and always will be her hero"

'I felt like a freak, then I fell in love with basketball'

Conroy was 14 when she was told she was cancer-free, and she returned to school with a whole new perspective on life.

"I was bald with no eyebrows or eyelashes, my face was really swollen from the steroids, I had braces and glasses and a big wheelchair that I couldn't fit into classrooms - I was a state, I don't know how I wasn't bullied," she says.

"But I just thought life was amazing. I was just so happy."

As time passed, she started to become "painfully self-conscious", trying to hide her prosthetic leg with baggy flares. She was "mortified" when she was first told by a basketball coach that she would have to remove it in order to play.

"I didn't know anyone who had one leg so I guess I felt like, and it's a strong word, a bit of a freak," she says.

It was Conroy's beloved father, Chris, who first introduced her to wheelchair basketball, though she readily admits she was apprehensive at first, thinking it "wouldn't be a real sport".

"I'd worked so hard to walk again, I didn't want to be playing a disability sport, but I was absolutely wrong," she says.

"Everything was the same as the running game, it was fast, it was dynamic, competitive, and really aggressive.

"I loved that, because as a sick kid, people could be so precious and careful around you, and I looked quite fragile and weedy, but it was rough and aggressive and I loved it.

"I was terrible at first though, absolutely awful."

'I'll never be more proud to represent GB'

GB women finished fourth at the Rio 2016 Paralympics

Thankfully, though, Conroy did improve and made it onto the GB squad. Her Paralympic debut came at London 2012 and she also played at Rio 2016, where the team finished fourth.

Four years on, GB - who won World Championship silver in 2018 - are ranked second in the world behind the Netherlands, and had been preparing for a gold-medal push at Tokyo 2020.

But then along came the coronavirus pandemic, postponing the Paralympics until next year.

"Initially, I was dreading the news, and I was incredibly disappointed - it would be weird if you weren't, you've been preparing for four years," she says. "But I think it is absolutely the correct decision.

"It could be the big celebration at the end of all of this. I'll never be more proud to represent Great Britain after seeing how everyone has come together through this, as a united nation. We're seeing the best of British again like in 2012."

For now, Conroy is training as much as she can at home, while also taking part in team sessions via Zoom and staying in contact with the team's psychologist and nutritionist.

Through this period of uncertainty, some old emotions are resurfacing for Conroy.

"In hospital, some of the things I felt then, I'm recognising some of those same feelings now," she says.

"Once you've given yourself the woe-is-me time, you can draw a line under that. Pity parties don't get you anywhere, you don't achieve much, but you can always control your attitude.

"As tough as this period is, I think we are all going to gain resilience from it and that in itself is a positive."