The lost lionesses

England's forgotten teenage football trailblazers

A 16-year-old English girl in an all-white football strip nervously clambers up on to a toilet seat in one of the Azteca Stadium’s cool underground dressing rooms.

She’s trying to get a glimpse through a high window of what awaits her.

It’s just before kick-off on a blazing August day in 1971.

Trudy and her mostly teenage team-mates are preparing to walk out in front of 90,000 boisterous fans in Mexico City’s packed, towering stadium for a crucial World Cup match.

Back home, where women's football is just emerging from a 50-year ban, the girls are used to playing in parks for a handful of spectators. So this is unlike anything they have experienced in England.

Their team coach needed a police escort with sirens wailing to get through the traffic and crowds to the ground. The players have been treated as celebrities and mobbed by fans from the moment they touched down in Mexico.

As kick-off approaches, Trudy climbs the stairs from the dressing room to the pitch. Her stomach turns another somersault as bright sunlight floods the mouth of the tunnel and the crowd noise swells.

Stepping on to the pitch under the intense midday sun feels like stepping into a furnace. She starts sweating before she's even broken into a jog. The deafening sounds of bangers, drums, trumpets, whistling, cheering and jeering fill the cauldron.

On top of the noise, heat and humidity, the team must also contend with the thin high-altitude air and fiercely competitive opposition.

They are playing the host nation in their second match of the tournament. The first was less than 24 hours ago, and the captain is playing on with a broken bone in her foot.

No English women's team has ever played a game like this.

But this is not their only battle. When they return home, they will find themselves in the middle of another struggle, this time over the future of women’s football.

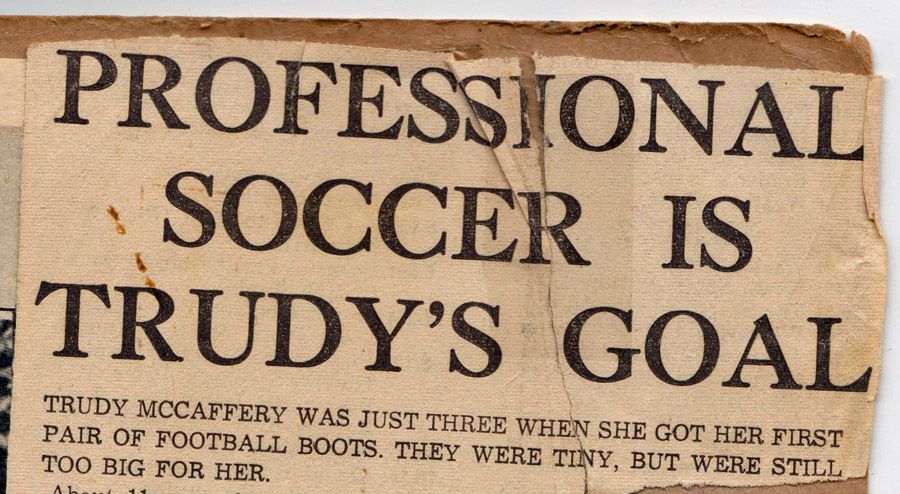

Trudy McCaffery started playing football almost as soon as she could walk. She used to kick a ball on the sidelines when her dad took her to games he refereed.

In her teens, when a boyfriend wanted to buy her a ring, her response wasn't the one he expected.

She asked for a pair of football boots instead.

She laughs as she casts her mind back. "'Blow the ring, just get me the boots!' They were the best football boots I had in all my life.”

Like Trudy, most of the players who travelled with the unofficial England squad to Mexico in 1971 were obsessed with football from an early age.

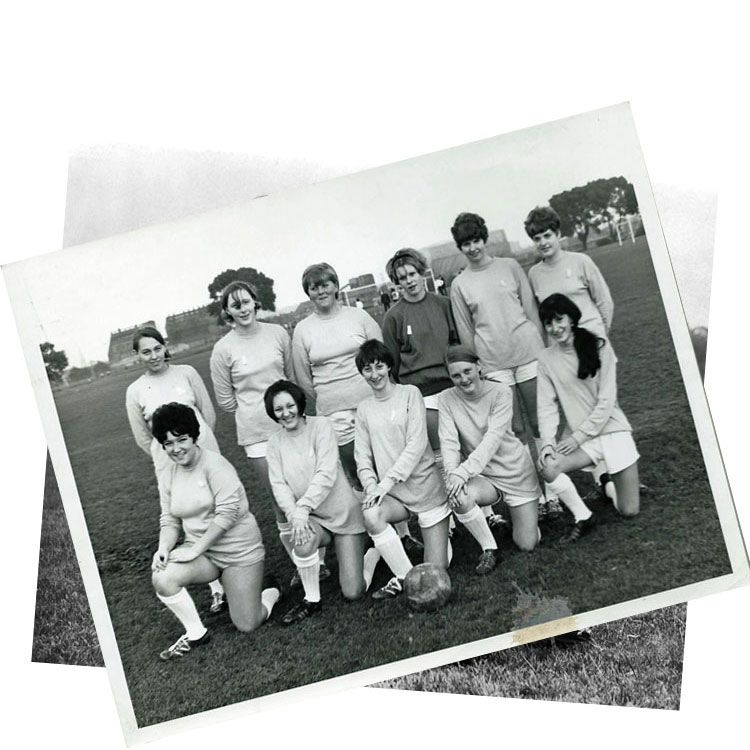

Many had been banned from joining boys’ teams at school. The only way Gill Sayell, a small, speedy winger, was allowed to play for a local lads’ team was to pretend to be a boy called Billy.

“I can remember still kicking the ball around on the green when schoolfriends of mine were going out to discos,” she says. “I wasn’t interested in that – just the football.”

Sayell was 14 when she graduated to Thame Ladies, which had been founded in the Oxfordshire town in 1969.

Like other teams, they made do with whatever facilities were to hand, getting changed in the scout hut down the road and, after one particularly muddy game, traipsing through the streets to be hosed down in the cattle market.

An average women’s match would be watched by a couple of dozen people – some of whom happened to stumble across a game in the park.

“It was one man and his dog,” says striker Janice Emms (née Barton), only slightly exaggerating. “Some people who just happened to be there would perhaps stop and watch for five or 10 minutes. But there were hardly any.”

Those who did turn out in support were enthusiastic, but some of the casual onlookers were less so.

“You’d get so much abuse from them. They just regarded it as a joke, girls playing football. Nobody took it seriously. We did.”

There had been an earlier time when big crowds did take women's football more seriously, however.

During and after World War One, women’s teams partly filled the gap left by the young, fit men who had gone to fight. On Boxing Day 1920, 53,000 people packed into Everton's Goodison Park to watch the most famous women’s team, Dick, Kerr Ladies, play a fundraising match for war charities – with at least 10,000 more locked out.

But with the chaps back home and the Football League resumed, the FA declared the following year that “football is quite unsuitable for females”. They also claimed some takings from charity matches weren’t reaching their intended causes. So the FA banned registered clubs from letting women play on their grounds or with registered referees.

Women’s football was suppressed for decades. Some clubs kept playing on company fields, public pitches and other sports grounds. But it took until the 1960s for a resurgence in women’s football to stir as women found new freedoms and the 1966 World Cup heroes became idols to both girls and boys.

In 1967, when Tottenham won the FA Cup, supporter Patricia Gregory was watching their victory parade when a question popped into her head.

“I was standing in the crowd and thought, why don’t girls play football?”

She had no idea about the FA ban. So she wrote to her local paper and posed that question. “I got responses from girls saying, ‘I want to join your team.’ Of course, I didn’t have a team – so we formed a team in my parents’ front room.

“That’s when I first came across all the problems because when I went to the council to find training facilities, they wouldn’t hire me anything.”

Around the same time, 30 miles north, another team was being assembled.

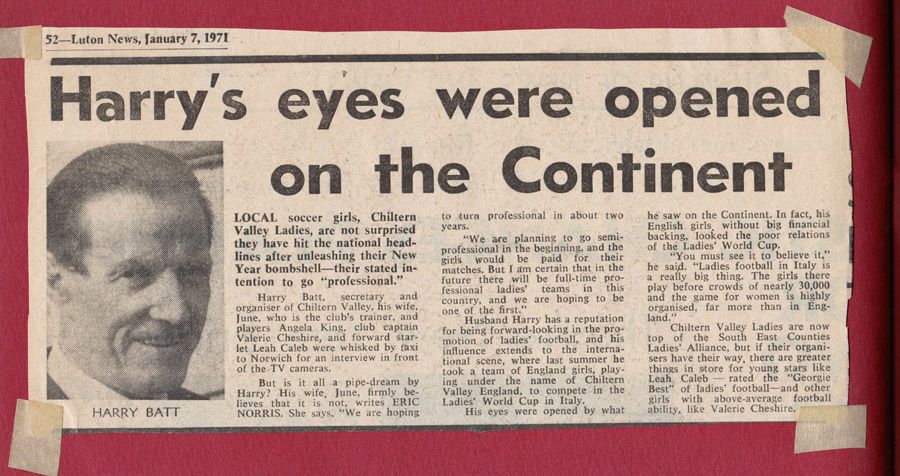

Harry Batt was a bus driver who spoke five languages and had been shot and wounded during the Spanish Civil War. At 60, he was from an older generation. But he asked himself the same question.

He set about finding players to form a team in Luton. Chiltern Valley Ladies lost their first match 12-0, but rapidly improved and attracted the best local talent.

Patricia Gregory and Harry Batt were both part of the first governing body, which became the Women’s Football Association (WFA) in 1969. By 1970, the WFA had persuaded the FA to overturn its ban.

But Batt was a maverick with an ambitious vision for women’s football that set him on a collision course with the rest of the WFA.

He had made contacts in Europe and was invited to take teams to unofficial European Championships and World Cups in Italy in 1969 and 70. With Uefa and Fifa not yet bothering with women’s football, a group of Italian businessmen took it upon themselves to stage international tournaments as the Federation of Independent European Female Football (FIEFF).

Batt's teams were billed as England - angering the WFA, which was in the process of putting together its own official national side.

Batt's sides consisted mainly of his Chiltern Valley players, joined by some top talent from other clubs. In Italy, they played in proper stadiums to decent crowds. It was the most advanced country for women’s football at the time, with a professional league.

But nothing they found there prepared them for the experience that would greet them in Mexico in 1971.

Welcome to Mexico

Bleary-eyed after the long journey from London to Mexico City, 15-year-old forward Chris Lockwood, wearing the team’s uniform of white crimplene skirt, white blouse and checked blazer, was dazzled by flashbulbs as she stepped off the plane.

Turning to a team-mate, she remarked that there must be someone famous on their flight. Then the penny dropped.

“It was us! We couldn’t believe it. And there were crowds and crowds. It was like going into the Tardis and coming out and you were in another world.”

The press photographers and the several hundred fans chanting and waving banners were indeed there for them.

Despite their fatigue from the flight – the first time most of them had been on a plane – several girls were immediately whisked to a television studio for an interview. Adverts for the tournament were constantly on TV.

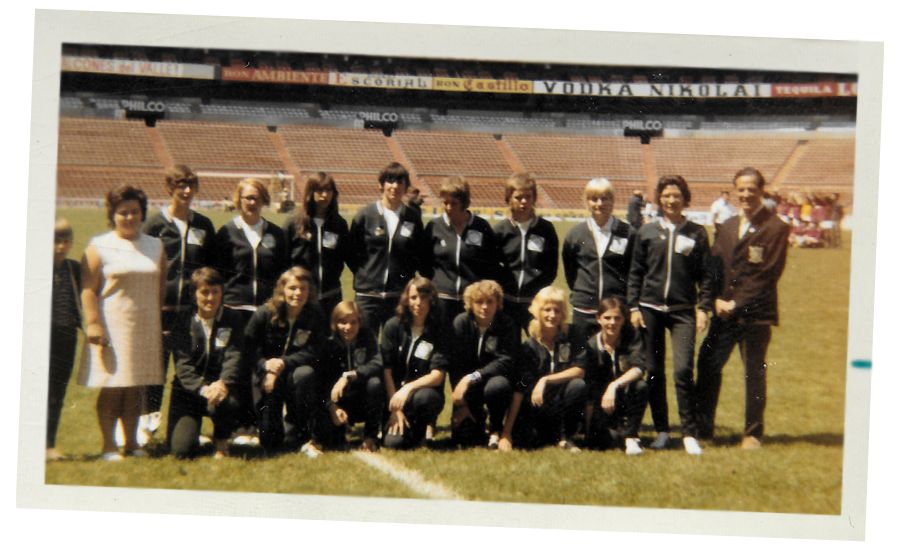

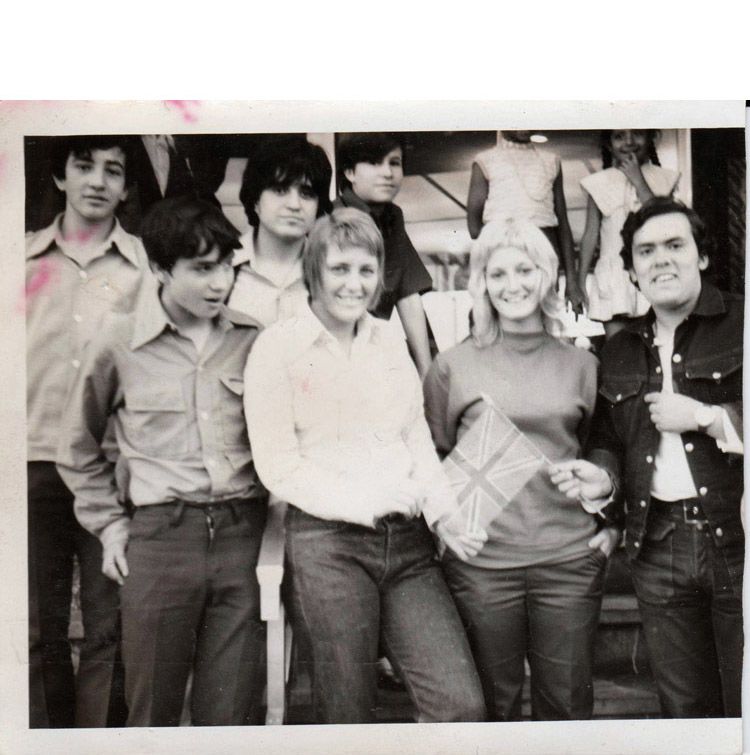

The 14-strong British squad, only two of whom were over the age of 20, had two weeks to acclimatise before their first match, staying at the hotel where England’s men had been based during their World Cup the previous year.

The male team had caused some bad feeling when captain Bobby Moore was arrested on suspicion of stealing a bracelet in Bogota in the build-up to the finals. But the locals took to the English women straight away.

Fans besieged the players’ hotel, turned up at their training ground, asked for autographs, showered them with gifts and even stopped traffic to surround and enthusiastically rock the team bus - despite the fact the players had a police escort wherever they went.

“It was terrifying. I can still feel the bus. It wasn’t shaking that much – the wheels weren’t coming off the floor – but it felt like it!"

The players' popularity was down to the fact they took an interest in the locals, Chris Lockwood believes. “We were down to earth, and they liked that. We were approachable.

“I remember them saying, ‘You talk to us when you’re signing autographs’. But to us it was only natural. We would like to know about them. But maybe some people wouldn’t bother.”

After the swinging 60s, England was glamorous in the eyes of the Latin American public. The girls were nicknamed “las chicas de Carnaby Street” by one Mexican paper. They were actually schoolgirls, bank clerks and telephonists from Bedfordshire, Hampshire, Buckinghamshire and Leicestershire - but they fitted the bill.

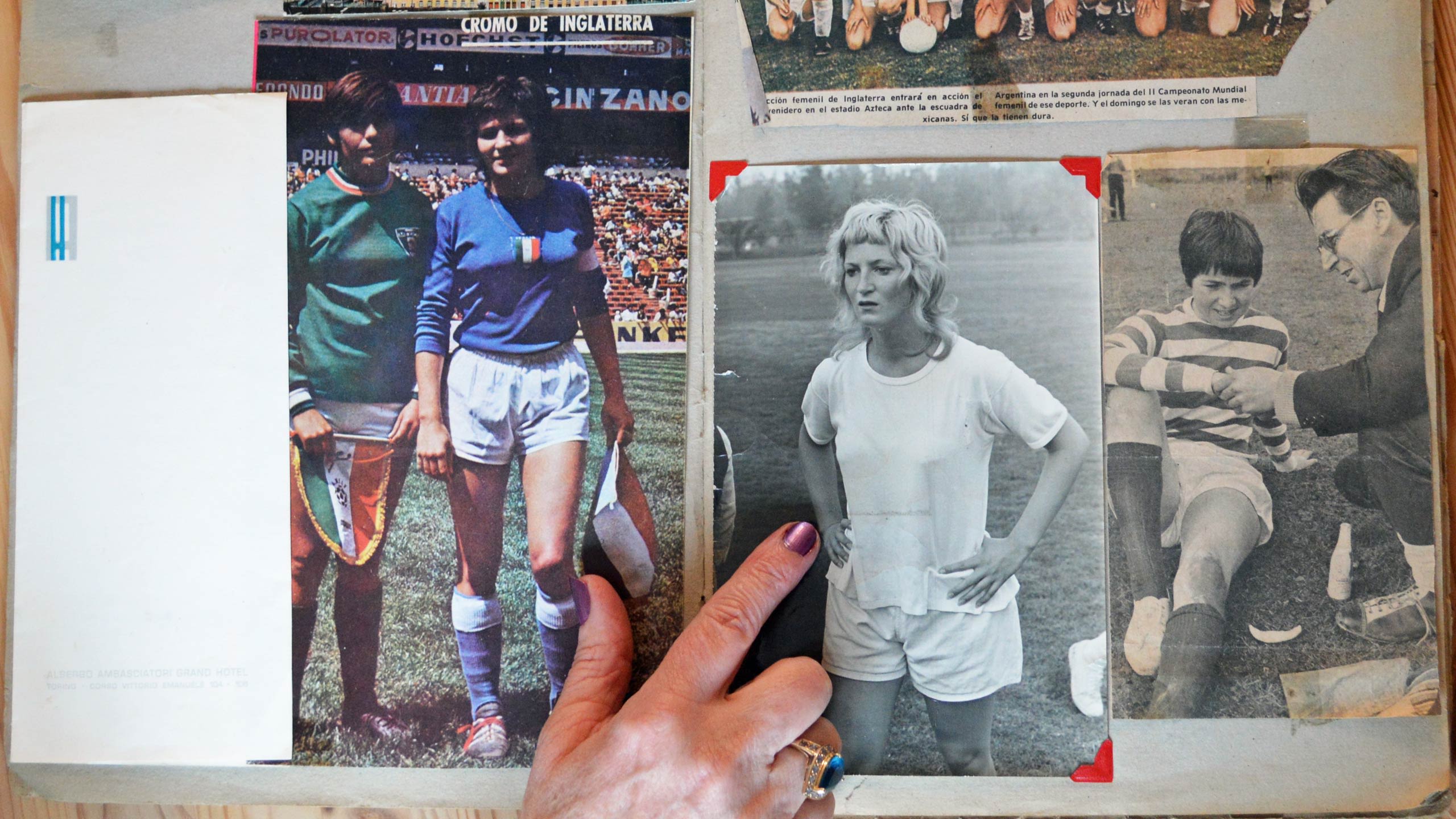

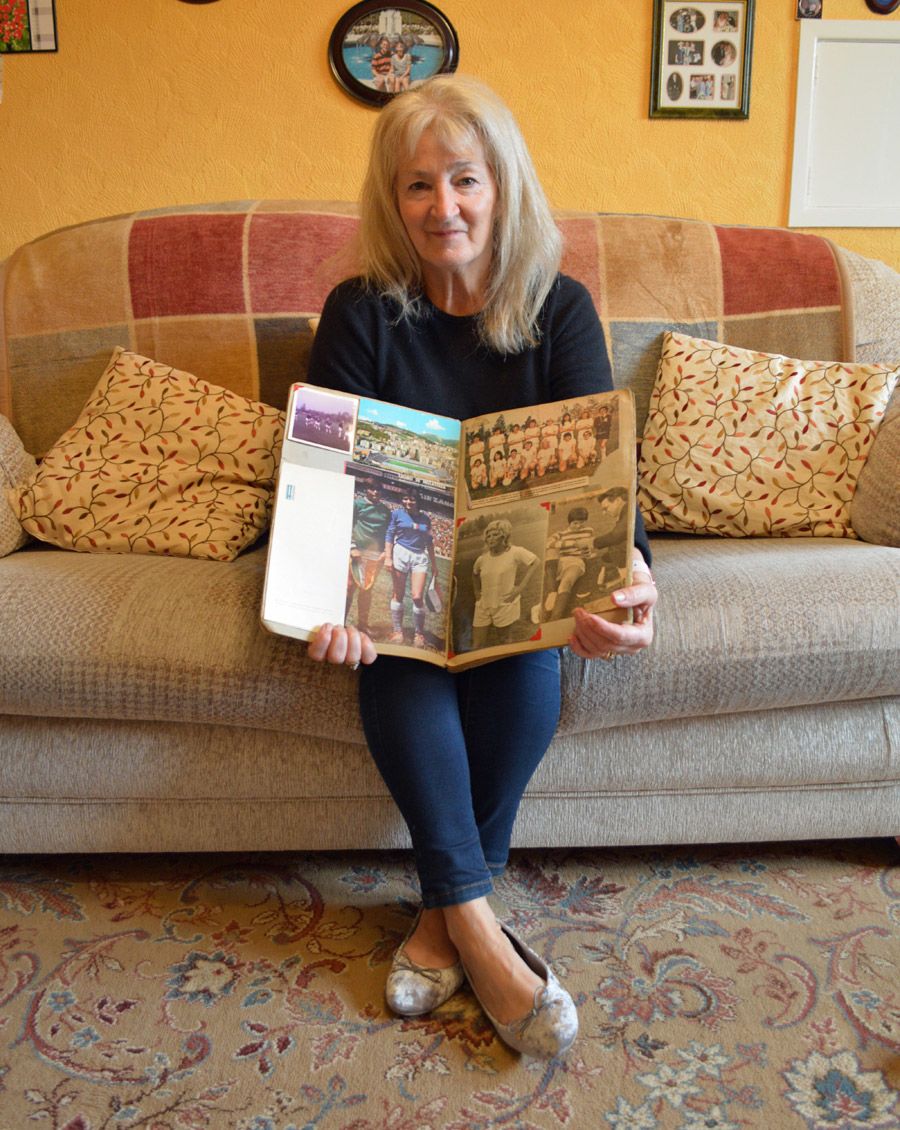

Trudy’s exotic blonde hair was almost always mentioned in newspaper articles, which also reported that she had “hundreds of admirers”.

“You couldn’t believe the fact you were some sort of star, even if it was just for that short period of time. That’s what it felt like.”

At just 13, Leah Caleb was the youngest member of the squad. Her skilful style saw her compared with her idol George Best. She was also popular, especially with teenage Mexican boys.

“Two boys walked literally from outside Mexico City one day to see me with a bunch of flowers,” she recalls. “They would have been roughly my age. That’s just amazing.”

Victor Fonseca, another fan, persuaded his dad to take him to try to catch a glimpse of Leah. He was the same age as the English youngster and had fallen in love after seeing her photo in a paper.

"My heart leaped," he remembers. "I went from being a boy to becoming a man. It was an experience that could seem corny, but it was really significant in my life."

During the build-up to the tournament, Mexican newspapers carried photos of the players in their hotel, in shops and by the pool, as well as interviews in which they made bold claims about who they would like to face in the final.

At home, there was nothing like the same coverage, but there were snippets in the papers. George Best himself got wind of the girls’ experiences and mentioned them in his column for Fabulous magazine.

“It all sounds like a dream to me. But it happens to be true. The way it’s going, I’ll be the bloke in the stands and my girlfriends will be out there playing,” he wrote. “Of course I’m only kidding. I hope!”

He was right about it being a dream.

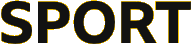

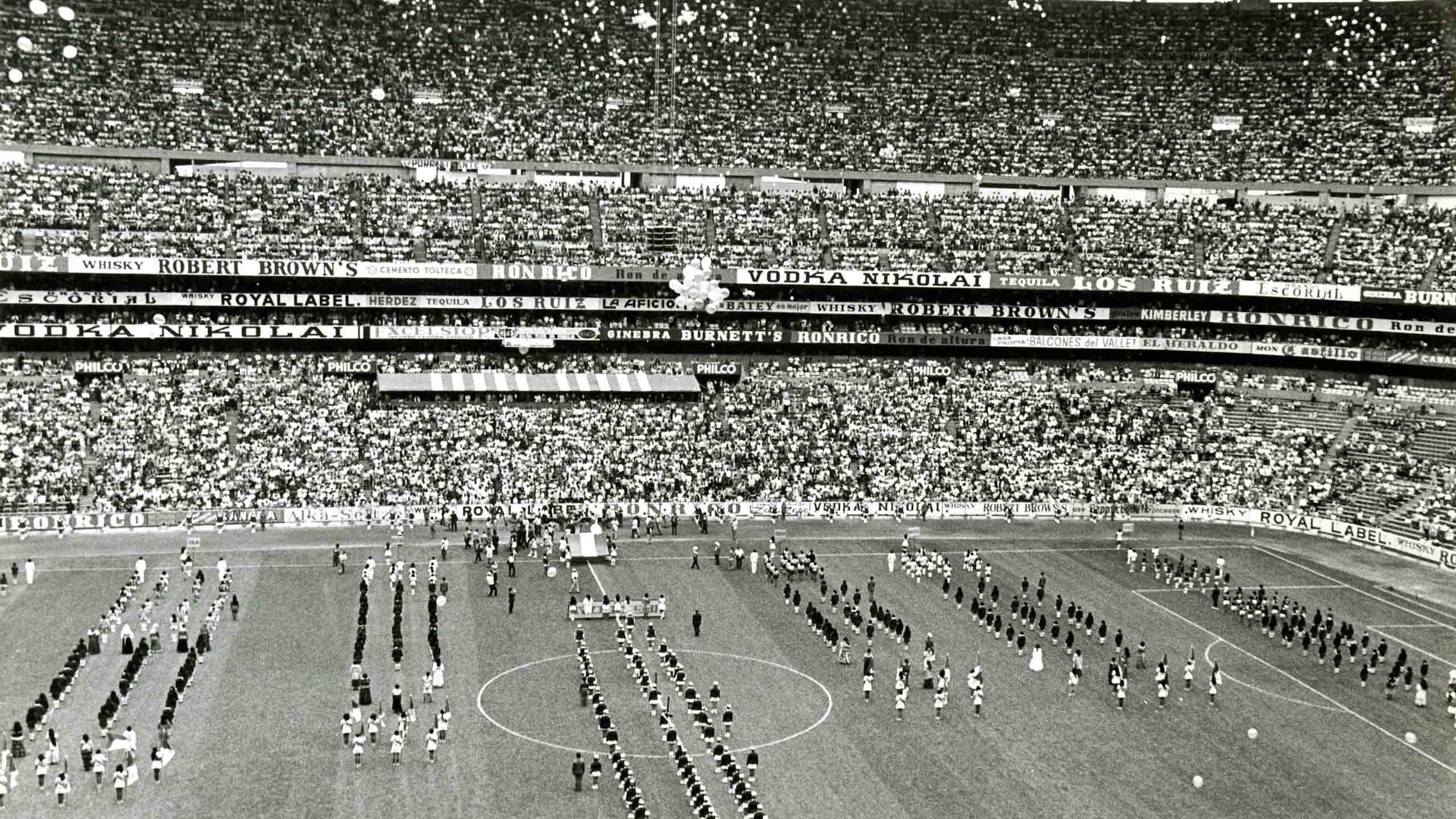

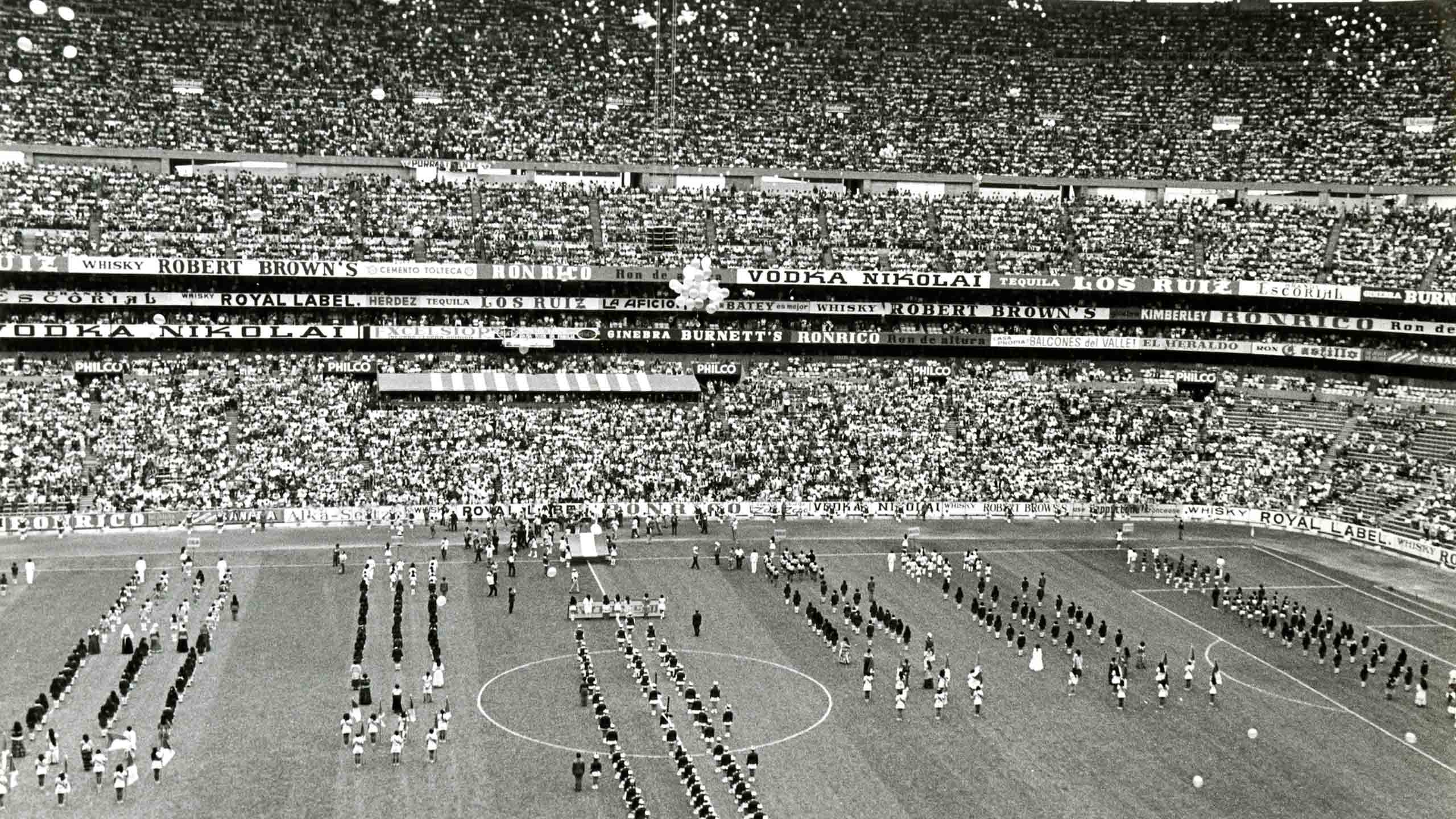

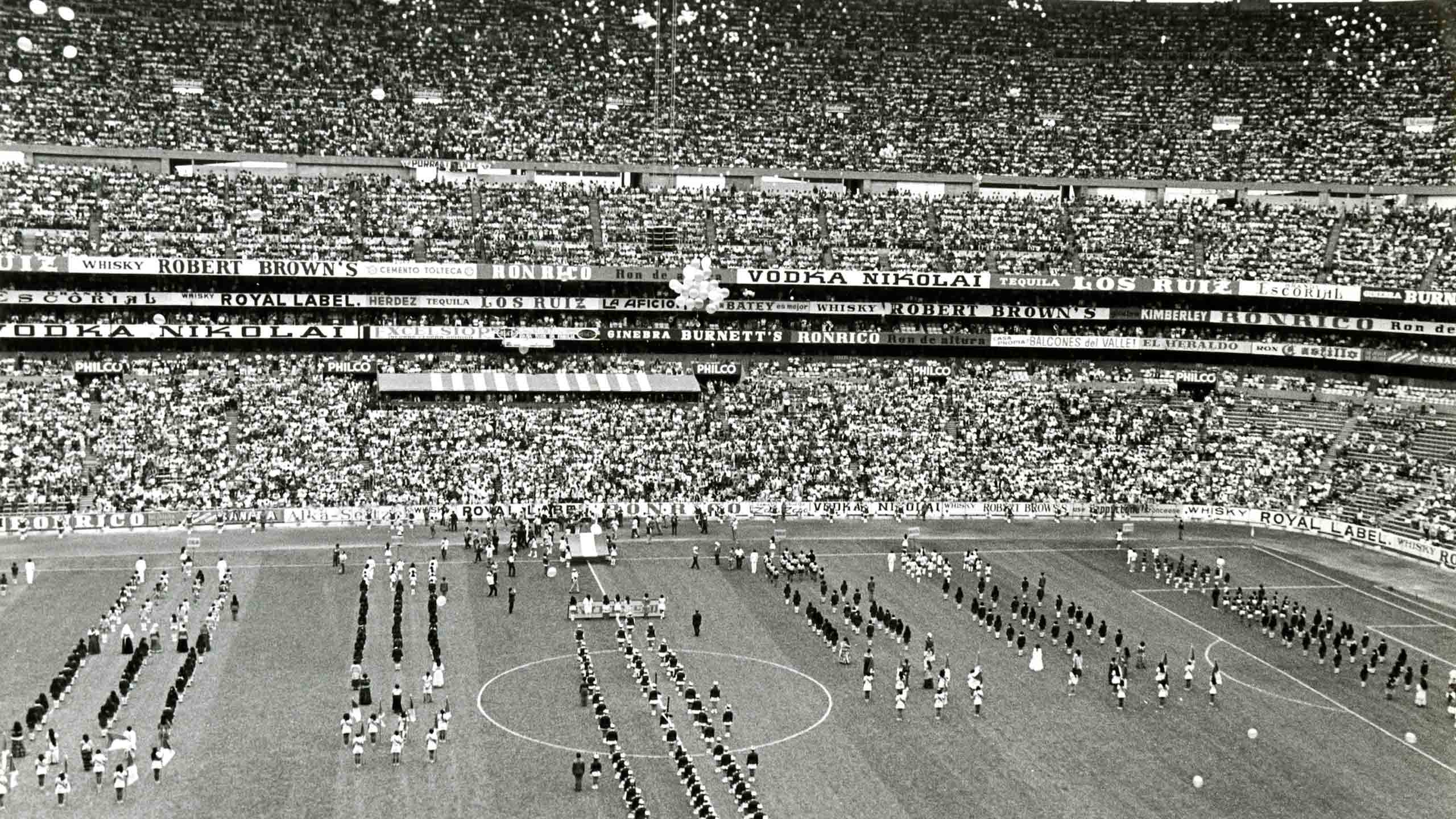

But it was only when the players got to the Azteca for their first match that the reality of their task hit them.

The Mexican newspapers and stadium scoreboard billed the team simply as Inglaterra, despite the fact they officially called themselves British Independents and didn't wear the Three Lions in an attempt to appease the WFA.

They had been drawn in Group A with Mexico and Argentina, and the hosts beat their fellow Latin Americans 3-1 in the opening match.

The English team’s first game was against Argentina. The Mexican papers made England the favourites, but the Argentines needed to win to stay in the tournament.

Around 25,000 people turned up to watch – far fewer than the steep Azteca stands could hold, but still far more than the players had ever walked out in front of before. The noise, even in a quarter-full stadium, was daunting.

“To be playing before one man and his dog, and then you walk out to THAT… It did hit you,” says Janice Emms, who had quit her job as a bank clerk in Biggleswade, Bedfordshire, to go on the trip. (If the surname is familiar, her daughter Gail won an Olympic badminton silver medal in 2004.)

“You couldn’t help but get nervous because you’d never experienced anything like it," Janice adds. "You felt tiny. The pitch was huge as well. We weren’t used to it.”

Argentina took the lead on seven minutes but England equalised six minutes later through 15-year-old forward Paula Rayner.

The biggest shock was how physical their opponents were. “They were animals,” remembers Janice.

Trudy McCaffery recalls: “They were going to win at all costs, and it didn’t matter if you got in the way. They were quite prepared to run over you rather than run around you.

“Had we been playing more on that international circuit, perhaps we would have been playing the same way. Whether that would have been a good thing, I don’t know.”

Captain Carol Wilson, 19, injured her foot but played on. Chain-smoking and chain-swearing Harry Batt prowled the touchline. In the dugout was his wife June, who helped run the team. Their 10-year-old son Keith was the mascot.

“It was a battlefield,” Keith remembers. “I remember mum saying, ‘Pull the girls off. Stop the game because it’s out of control.’”

Harry didn’t take her advice and things got worse when Janice was sent off. She says it was because she left the pitch without permission so she could remove her shinpads. She wasn’t used to wearing them, and was struggling in the heat.

“The ref came over to me and he went ballistic, and he sent me off. Harry Batt was going bananas.” She remembers being let back on shortly afterwards, however, as a result of their appeals.

But she couldn’t help her side overcome the Argentines, who went on to win 4-1, with all four goals scored by Elba Selva.

The English players were crestfallen. Harry Batt told reporters: “We tried to play clean English football, but things didn’t go to plan… The girls were hacked to pieces. It was absolutely diabolical. They came after our blood.”

A headline in one Mexican paper heralded Argentina’s “surprise victory”. But Argentine goalkeeper Marta Soler dismissed England by saying: “They simply have nothing to do in this tournament.”

FIEFF vice-president Marco Rambaundi remarked afterwards: “I’m under the impression that these girls came here on holiday.”

The English players, bruised and downhearted, boarded the bus back to the hotel. The sombre atmosphere lifted a little when someone cried: “Come on, we have to move on, because tomorrow we are going to win!”

By then, it was past 6pm. Their next game was at noon – less than 18 hours away.

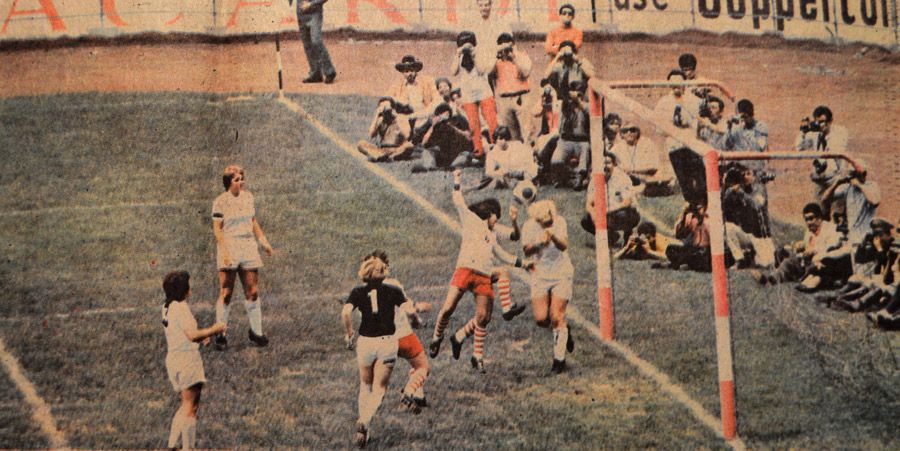

It was the daunting match against Mexico in front of the huge partisan crowd.

Floating in the Azteca Stadium

“Inglaterra” banners flew from the team coach as it sped to the Azteca Stadium, slowing only as it met heavy traffic and thronging crowds.

The car parks were jammed and several accidents held up the roads. There were many more people than the previous day.

“It seemed as though the whole of Mexico had turned out,” Trudy McCaffery wrote afterwards in her own match report on hotel notepaper.

When they finally got into the stadium, the crowd noise echoed around the dressing room. After a glimpse of the crowd and a “last-minute rush for the toilet”, as Trudy put it, both teams lined up in the tunnel.

“As we walked out, after the cool of the underground dressing rooms, it was like a blast furnace and I began sweating straight away.

“There was a glaring yellow sun directly above us and not one shadow to protect anyone.”

There is no official attendance, but one Mexican paper put the size of the crowd in the Azteca cauldron at almost 90,000. Another estimated it at 95,000. It remains the highest ever attendance for a match involving an English women’s team.

The current official world record for any women’s football match is 90,125 for the 1999 World Cup final in Pasadena, California.

The Mexican crowd had been warmed up by a motorcycle stunt display and a 30-minute match between singers and actresses (the actresses won 1-0).

When the main event began, despite the popularity of the English players over the previous two weeks, the home crowd was firmly behind their national team.

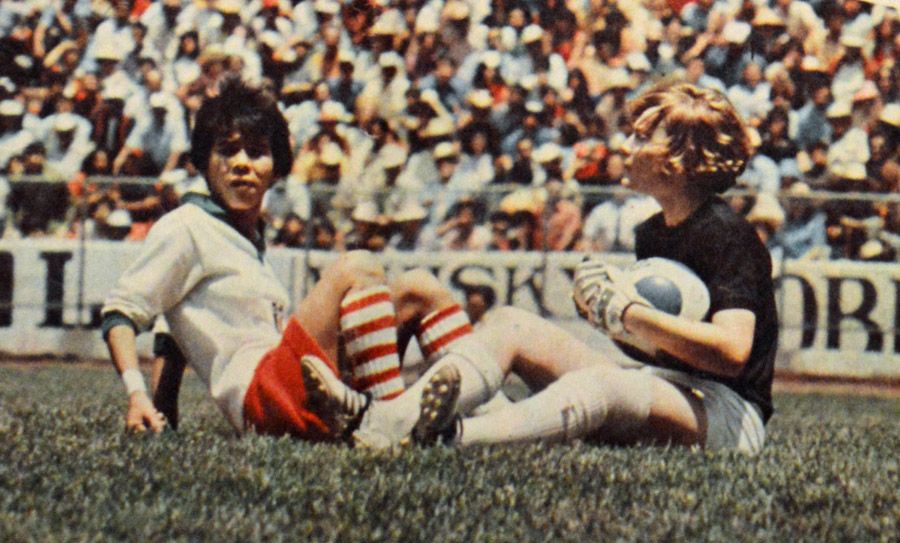

Mexico, inspired by Alicia “La Pele” Vargas, took the lead after just three minutes. The English team performed better than they had done the previous day, but went in 1-0 down at half-time.

The Mexican players, while physical, were less robust than the Argentines. But the combination of two demanding matches within 24 hours and the heat, altitude and the huge, vociferous crowd began to take its toll.

Trudy was on the bench but came on at half-time when Marlene Collins got injured. The second half unfolded “like a dream”, Trudy wrote.

“In boiling hot humidity, players floated past and back again. I stuck my boot in two or three times, took some throws and free-kicks and generally tried to breathe.

"We were all having the utmost difficulty with the heat and breathing problems, but for a short period seemed to be on top, until the second goal was scored.”

The home side scored two more without reply. Meanwhile, the England players were dropping like flies.

In Trudy’s account of the match, she recorded the final score as: “Mexico 4 – Us 1 broken leg, 1 broken foot, 3 strained ligaments, 1 cartilage, 1 badly bruised shoulder & various other bruises, cuts, bumps and knocks.”

Sixteen-year-old forward Yvonne Farr suffered a broken leg, while Carol Wilson discovered she had broken a small bone in her foot the day before. In total, eight English girls were treated in hospital. Most of the team needed oxygen after the game.

“It's too much for the girls to play two games in less than 24 hours,” Harry Batt complained. “You don’t even see this in men's football.”

Aside from the physical injuries, the two defeats wounded the English players’ pride - and ended their dreams of World Cup success.

The crowd may have been against them during the match, but afterwards a group of Mexican fans gathered to applaud as they drove away from the stadium.

As their coach slowed down, fans passed gifts to the English team, and the girls handed out pennants and badges in return.

“There were no tears this time,” a Mexican reporter wrote. “They were sure that they tried their best.

“They did not win in the World Cup as they wanted to, but they definitely won the sympathy of the people, who before knowing them disliked anything to do with the English stiff upper lip. They created a new and positive image.”

That should have been the end of their World Cup adventure. But the players had made such an impression that they were asked to stay on.

Despite the injuries, there were no hard feelings between the English and Mexican players. In fact, the Mexican team threw a party for their English counterparts, forming a guard of honour for Carol and Yvonne as they arrived with legs in plaster.

It was meant to be a farewell party, but a 5th/6th place play-off match with France was hastily arranged.

They had six days to prepare, but that wasn't enough for some of the English team to recover. The squad was so ravaged that they had to borrow three Mexican players.

Inglaterra went 2-1 up, with Janice scoring both goals. For her second, she beat two players before firing past the goalkeeper.

She wrote in her scrapbook that it was the "proudest moment of my life".

“I’m not sure how many people in the UK have actually scored two goals in the Azteca Stadium.”

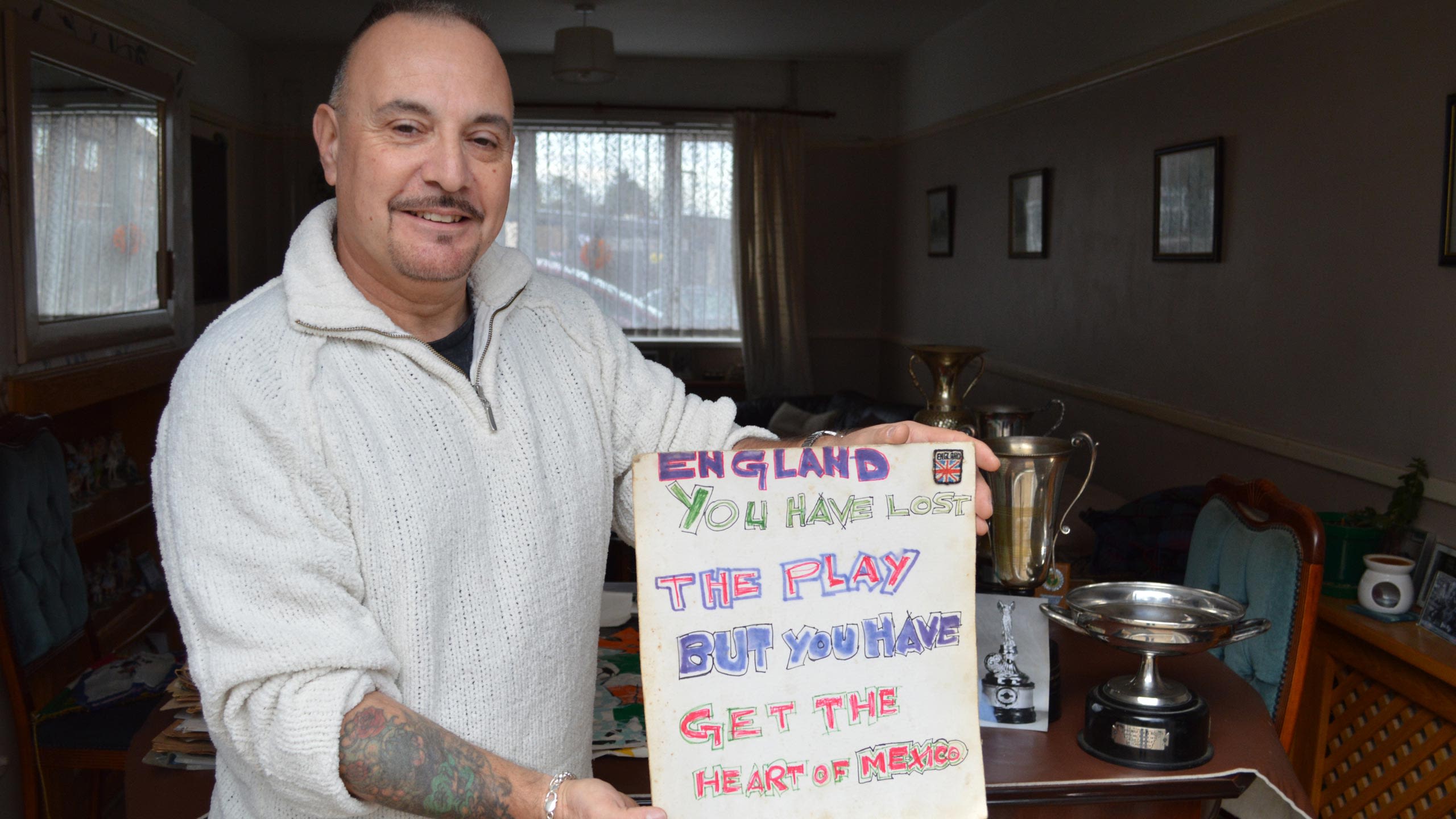

But the British Independents eventually lost 3-2. Before the team returned back home and back to reality, a Mexican fan took a homemade placard to the hotel to make sure Harry Batt and his players were in no doubt about how well-loved they had become during their four-week adventure.

In colourful letters and imperfect English, it read: “England you have lost the play but you have get the heart of Mexico.”

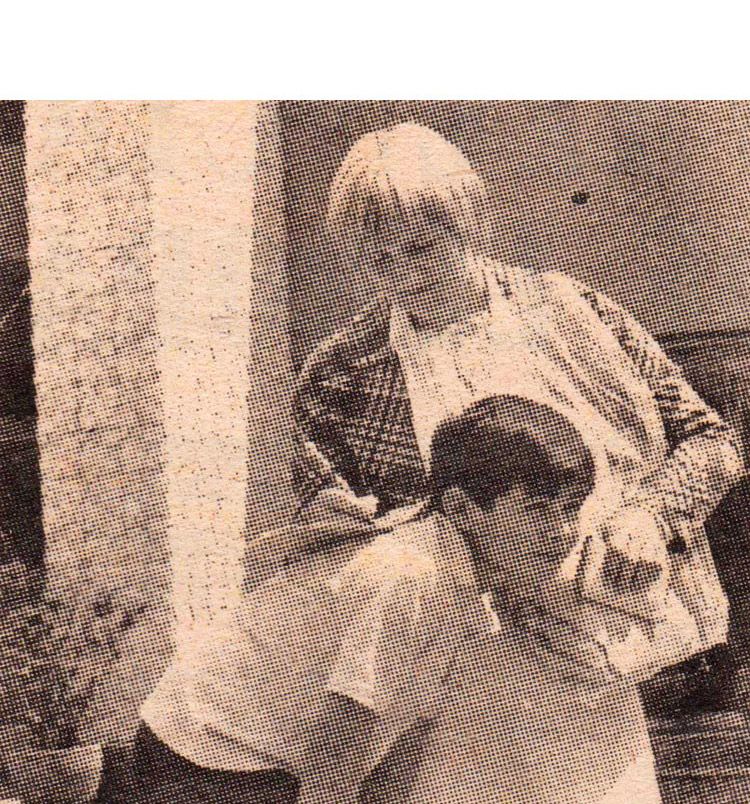

Harry and June Batt's son Keith with the sign made by a Mexican fan

Harry and June Batt's son Keith with the sign made by a Mexican fan

Denmark went on to win the tournament, beating Mexico 3-0 in the final with a hat-trick from 15-year-old Susanne Augustesen in front of a 100,000-strong crowd.

In the UK, much of the press coverage focused on the battering the British team took. There were headlines like “Soccer girls limp home to a rumpus” and “Football mayhem as women are hurt”. The Luton MP even pledged to investigate the injuries.

A couple of weeks later, the Luton Saturday Telegraph carried a double-page spread about the “Soccer girls who won hearts of the Mexicans”.

But in a tone that was typical of English press at the time, they were billed as “footballing beauties”, and readers were told: “Don’t laugh – one day there may be a female Arsenal.”

The article quoted Harry Batt as saying he wanted women’s football to be taken as seriously in England as it was in some other countries.

He hoped to use his team's experiences in Mexico, and lessons from the success of the tournament, as a launchpad for taking women’s football to the next level of professionalism and popularity in England.

Big plans and fading dreams

“He had this dream of women’s football,” Keith Batt recalls of his father.

“He talked about it for as long as I can I remember. ‘Women’s football,' he said, ‘it’s going to be the future’. Those were his words: ‘It’s going to be the future.’”

Harry and June Batt’s eyes had been opened by the professional women’s league in Italy, and they didn’t see why the same couldn’t happen in England.

Before the Mexico trip, Harry told a local paper he hoped to find a sponsor for Chiltern Valley Ladies within two years.

In another article, June said: “I am certain that in the future there will be full-time professional ladies’ teams in this country, and we are hoping to be one of the first.”

But that wasn't the WFA’s plan, and Harry’s relationship with the governing body had already broken down by the time he took his team to Mexico City.

The WFA felt he was trying to pass his team off as England. He was accused of luring players with the promise of “a place in the England team” and of using headed paper declaring himself the “England manager”.

Also, the WFA couldn’t consider any moves towards professionalism because its only meagre funding was a small government grant reserved for amateur sport.

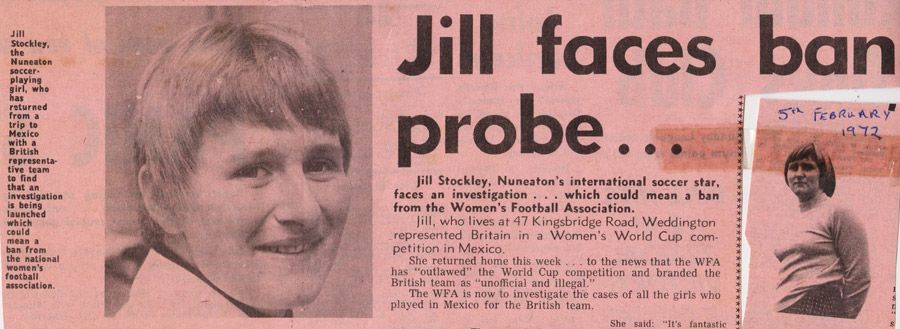

Two months before the Mexico trip, the WFA committee declared it would not recognise any team Harry or June Batt were involved with. The Batts were blacklisted.

That also meant Chiltern Valley had to be broken up. If the WFA found out that any Chiltern Valley players were applying to register with other clubs, they were banned for three months – unless they could prove they didn’t realise they had broken WFA rules by travelling to Mexico with the Batts.

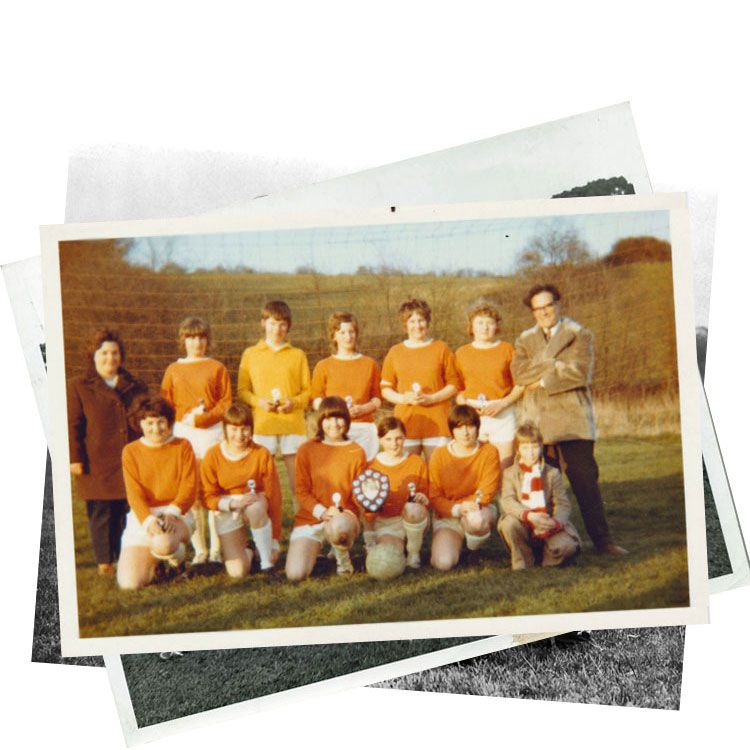

At that time, the WFA was working towards setting up its own official England women’s team. Unlike Harry Batt’s more ad hoc approach of inviting selected players to join girls from his club side, the WFA organised a series of nationwide trials.

Patricia Gregory had become the WFA’s honorary assistant secretary and went on to be its secretary and chairman. “We had a fledgling organisation. We were trying to do the best we could for everybody,” she explains. “And that relied on being fair to everybody.

“You couldn’t have anybody being rogue and taking a team, whatever the team was, and calling it something it was not entitled to be called. It wasn’t fair to all the other players that we were trying to represent and look after.

“He didn’t just do it once. He went to two Italian competitions [as well as Mexico]. I still think it was right to stop somebody portraying a team as England that wasn’t England, or even Great Britain. That was not fair on everybody else.”

The official WFA-backed England team was assembled by November 1972, beating Scotland 3-2 in their debut match in heavy snow in Greenock.

The first official England women's squad in 1972

The first official England women's squad in 1972

Harry Batt was a shrewd and persuasive operator who successfully put his team on the world stage. Whether he really could have organised and raised the profile of women’s football in England on a wider scale - beyond his team's own exploits - is another matter.

But after Mexico, he was involved in another plan that could have catapulted women’s football to the big time.

Ted Hart, who had worked as a PR man for England during the 1970 men's World Cup, approached Batt with the idea of holding another women’s World Cup at Wembley in 1972.

The crowds in Mexico had proved such a tournament could be a success. Hart had the backing of 1966 heroes including Bobby Moore and Geoff Hurst, and a pledge of £150,000 sponsorship.

Hart suggested that two England teams could take part - an A team assembled by the WFA and a B team put together by Batt. The two factions would have to bury their hatchet first, though - but there was no way the WFA would let that happen.

The WFA voted on whether to host the World Cup – on two conditions. Batt could not be involved, and nor could any teams connected to FIEFF, which had by then been banned by Fifa. The FA warned the WFA off, saying the plan was an attempt at “blatant exploitation” by the sponsors.

The WFA committee was split. In a vote, the idea was initially passed 6-5. But the vote was controversially re-run twice, eventually ending in a 6-6 deadlock. WFA chairman Pat Gwynne used his casting vote to reject the plan. A vote of no confidence was called by those unhappy with how the process had been handled. That ended 5-5. Deadlock.

Ted Hart later wrote to the WFA in dismay that they had spurned the opportunity to “put women’s football firmly on the map” and “convince the television millions that the women’s game, played at its highest level, is both skilful and entertaining”.

Maybe the plan did come too soon. The World Cup was to have taken place before the WFA had even assembled its first official England team. The WFA suggested staging the Women’s World Cup in 1973 instead, but by then the sponsors had pulled out.

Hart and his backers then proposed sponsoring the top teams to form a breakaway superleague, from which they would select an England team to play in another World Cup in England. But not enough teams were prepared to take the risk.

Later in 1972, Harry Batt asked to be allowed back into the WFA fold once more, but to no avail. In the end, it would take decades for women’s football to get close to the profile he had hoped for.

Trudy McCaffery thought her dream of playing for a professional club was about to come true when she was told a couple of Italian teams were interested in signing her.

She had been spotted while playing in Batt’s side at one of the tournaments in the country in 1970, and was approached by a scout.

“I thought, how amazing is this?” she recalls. “I can probably actually make a career out of this. I will be able to play football in the way I’d wanted to.”

Trudy phoned her parents straight away. Her mum didn’t share her enthusiasm.

“She went, ‘Well you can’t do that. Your exams are coming up. You need to get home.’

"I wouldn’t say she was horrified, but she was absolutely determined that this was not going to happen. If it had been a boy, they probably would have said, ‘Fantastic, you have to go for this.’”

As far as her parents were concerned, women weren’t professional footballers. To be fair, it wasn’t until Trudy and her team-mates went to Italy that they contemplated it as a career option either.

“We had no idea until we got there how big ladies’ football was everywhere else apart from England.”

After the Mexico trip, and after her O-Levels, Trudy and her family moved to Lincolnshire, where her father – an RAF flight sergeant – had been posted. After playing to 90,000 in the Azteca Stadium, Trudy went back to turning out for a school team.

“To go from the level we were playing [at before Mexico] – what we were used to – and to be catapulted straight up and straight back down again, that was just a shock to the system.”

Trudy McCaffery went on to become a prison governor.

Harry Batt died in 1985. His last job was working in the kiosk at Luton bus station.

He was never the same after being forced out of women’s football, according to son Keith.

“That was probably the turning point in his life. He stopped being a dashing, handsome, full-of-life man and became an older man and seemed to lose his passion and drive.

“My dad didn’t show his emotions. In my life I saw tears in his eyes a handful of times but that was one of them. They hurt him.

“And in doing that they didn’t just hurt him, they set women’s football back 30 years.”

Patricia Gregory insists the WFA was doing the best it could, as fairly as possible. It was trying to organise and regulate clubs and leagues around the country as well as putting together an inclusive and representative England team - all on a shoestring, and run largely by volunteers.

Harry Batt did things his own way, and the Mexico players remember him fondly. “He just made things happen,” says Trudy. “On his own."

What if?

Where would women’s football be now if the FA hadn’t banned it in 1921? Or if progress had moved faster in the 70s?

Asked whether a professional league could have worked in England in the early 70s, National Football Museum curator Belinda Scarlett replies: “Well, it was possible in other countries so I don’t see why it wasn’t possible in England.

“Maybe it just needed people who were a little but braver, like Harry, to push for it, rather than people working within the structures of the FA. The WFA were very important, but they were a ‘safe’ organisation.”

Professor Jean Williams of Wolverhampton University, another authority on the history of the women’s game, says the Mexico tournament demonstrated its commercial potential.

“There were professional women’s leagues in Italy, so the economic argument was there,” she says. “They were backed by businessmen, they drew large crowds and they were played in major stadia.

“It was very possible. And that’s why historians of women’s football love the story of 1971, because it kind of proves it.”

Fifa records show that the first official Women’s World Cup took place in 1991 in China. In England, the FA took over the WFA in 1993. In 2000, it announced that there would be a professional women’s league by 2003. Fulham Ladies became the first professional club in 2000.

But Fulham went back to semi-professional status three years later and it took until 2018 for the Women’s Super League to go fully pro.

Big strides have been made, but the status of women’s football remains below that of the men’s game.

This year’s Women’s World Cup, which takes place in France in June and July, is likely to be the most high-profile tournament yet, and England's Lionesses are among the favourites.

They will be watched by tens of thousands at the grounds and by millions of people at home, with all games live on the BBC in the UK. With today's facilities and funding, they will certainly be better prepared than England’s original World Cup superstars.

But no matter what they achieve, not much can compare to the moment when a group of inexperienced teenagers ran out on to the Azteca Stadium turf in front of 90,000 deafening Mexican fans.

Thanks to all the Mexico 71 players, Keith Batt, Patricia Gregory, Prof Jean Williams and the National Football Museum.

Written & produced by Ian Youngs

Photos: El Heraldo de Mexico, El Sol de Mexico, Cine Mundial Archivo, El Nacional, Ovaciones, Excelsior, Val Hyde, Gill Sayell, Leah Caleb, Trudy McCaffery, Patricia Gregory, Ian Youngs, Getty Images, Luton News, Shutterstock

Video: Val Hyde

Sub-editors: Peter Scrivener & Jamie Strickland

Editors: Anna Thompson, Howard Nurse & Philip Dawkes

Translations: Carlos Este