The White Horse Final: 100 years on

The legend of the first Wembley FA Cup final and how a policeman and his horse helped avert disaster

When PC George Scorey entered Rochester Row police station on 28 April 1923 he was only after a cup of tea. Little did he know that it would be the beginning of his journey into football history.

Scorey, a member of the Metropolitan Police’s Mounted Branch, had spent that morning on duty in Westminster with his horse Billy.

He had started work at 6am and it had been a largely uneventful Saturday; just the usual London weekend hustle and bustle. The most remarkable thing about the day was the weather, with the Big Smoke basking in glorious spring sunshine.

That was about to change. On the outskirts of the city, a figurative storm was brewing.

Soon after entering the station, Scorey was collared by a concerned-looking inspector. The FA Cup final was on that afternoon and there were reports of trouble with the crowd. The PC was to get over to Wembley as quickly as he could and try to help sort it out.

Moments later, Scorey was back on Billy and heading up towards Edgware Road, all thoughts of that much-needed cuppa abandoned.

A few miles away, at the newly built stadium in the north-west of the city, chaos awaited him…

Scorey wasn't much of a football fan. Even if he had been, you could have forgiven him for knowing little about the two sides contesting the FA Cup final - the 48th in the competition's history - to which he was en route.

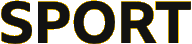

Lancashire club Bolton Wanderers were a founding member of the Football League in 1888 but, barring a couple of runners-up appearances in the cup, had failed to make a significant impact. The first quarter of the 20th century had seen them bounce between divisions one and two.

Bolton had previously lost two FA Cup finals - in 1894 and 1904

Bolton had previously lost two FA Cup finals - in 1894 and 1904

London’s West Ham United had even less notable history, having only entered the league in 1919, although they were on the up, with promotion to the top tier a near certainty to go alongside their cup run that season.

In Wanderers’ ranks was David Jack, who had scored a solitary winning goal in each of the three previous rounds, while the Hammers boasted talented forwards of their own in Vic Watson and Jimmy Ruffell. There were a handful of international caps sprinkled throughout the two sides; a couple for England, a few more for Wales.

Good players, then, but hardly household names.

West Ham competed in the Southern League and Western League before joining the Football League in 1919

West Ham competed in the Southern League and Western League before joining the Football League in 1919

The real draw for fans was Wembley itself. Or, as Scorey knew it at the time, the Empire Stadium.

In the decades to follow, the ground and its iconic twin towers would become synonymous with football and its oldest and most revered club competition in particular, but its original lofty purpose was much more fleeting and wholly unconnected to the beautiful game.

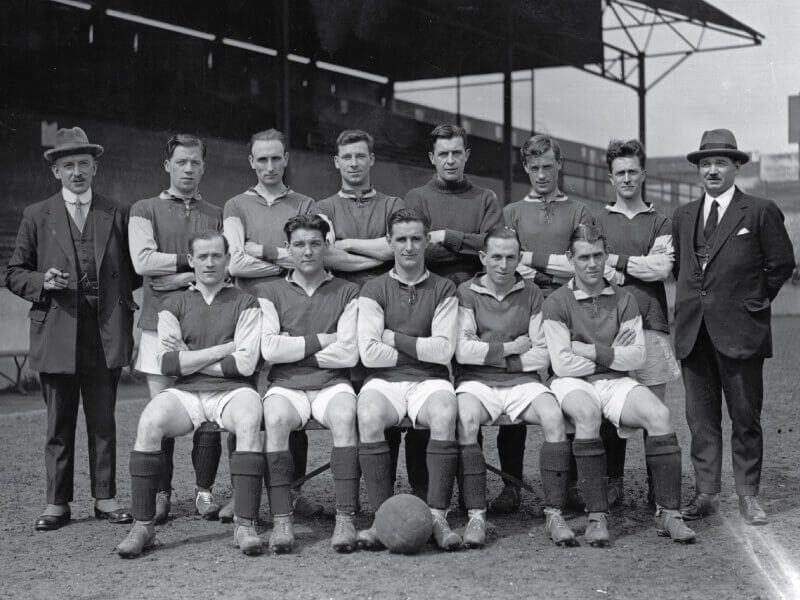

Britain's position in the world was faltering, its empire fading and appetite for its aims on the wane. There were now significant challengers on the global stage in the aftermath of World War One, most notably Japan and the USA.

To arrest this decline and to further the forward-looking ideal of a new commonwealth of nations, the British Empire Exhibition was devised in 1920. To be held four years later, it would showcase British greatness, stimulate trade and strengthen faltering bonds with the dominions. The stadium was to be its architectural and spiritual centre.

London was already littered with monuments to Britain’s perceived might. Along Scorey’s journey to Wembley alone he would pass near to Buckingham Palace and the arch and statue dedicated to the Duke of Wellington. Marble Arch would be one of the final significant landmarks before he pushed on out into open country and on to Wembley.

Furthermore, the site to which he was heading had itself once been the intended home of Britain’s version of the Eiffel Tower. However, issues with construction meant work was halted with this having reached just 47 metres of its planned 366-metre height. It would come to be mockingly known as the 'London Stump' or 'Watkin's Folly' after the driving force of the project, railway entrepreneur Sir Edward Watkin, before being dynamited out of existence in 1907.

A site map of the 1924 British Empire Exhibition

A site map of the 1924 British Empire Exhibition

The Empire Stadium’s pristine, imposing white exterior had been designed to embody majesty and industry, in both senses of the word. Inside, cherished British values of fair play, revelry and the stiffest of upper lips would be showcased through sports, pageants and military demonstrations.

The hope was that such virtues would endure, but there was no such long-term designs for the stadium itself, the original plan being to demolish the vast concrete bowl once the exhibition had ended.

That changed in large part because of an unexpected request from the Football Association.

After struggling in ill-suited stadiums after the war, the English game's governing body needed a more fitting venue for its showpiece event.

The 47 previous FA Cup finals had been held at a variety of grounds, predominantly the Kennington Oval and then Crystal Palace. With the latter still in the possession of the military and in dire need of renovation, the three finals prior to 1923 had been staged at Chelsea's Stamford Bridge but this was woefully inadequate to house the kind of attendances desired.

In Wembley, they spied a timely solution rising from the dirt. A 21-year contract was agreed and a fire lit under construction.

It took exactly 300 frantic days from the first shovel hitting the ground to complete construction, with the final brick laid on 23 April - well ahead of schedule for the exhibition and just five days before Bolton were due to face West Ham.

The cost was estimated to be between £750,000 and £800,000. When adjusted for inflation, this is equivalent to a still pretty reasonable £46m today – not far off the amount Newcastle reportedly paid in January 2023 for forward Anthony Gordon.

Once finished and prior to opening, labourers undertook rigorous testing to ensure the site was capable of standing up to use by crowds, including the placing of sandbag ‘spectators’ in seats inside the ground.

Builders were also employed to march repeatedly around the stadium to test how the 25,000 tonnes of concrete, 1,400 tonnes of structural steelwork and half a million rivets used in the construction would hold up under the expected footfall.

The 'Twin Towers' were the most iconic aspect of the old Wembley Stadium's design

The 'Twin Towers' were the most iconic aspect of the old Wembley Stadium's design

According to an article in The Engineer, dated 6 April 1923, part of the testing involved a group of 1,280 men being marched into the stadium, in companies, and led to fill seats behind the Royal box.

The Engineer article continues: “It was quite obvious that the majority of these men had seen service in the war otherwise we do not think it would have been possible… for them to act in such unison with such wonderful precision.

“Under the command of Captain F.B. Ellison, who, during the course of the work had been the resident architect, the men were put through a series of movements, such as standing up, sitting down, swaying from side to side and backwards and forwards... the men appeared to the onlooker to be wonderfully together in their movements.

“Then the instructions were to shout and jump about and wave the arms frantically so as to produce as nearly as possible the movements of a crowd watching an exciting match.”

The Empire Stadium was designed to house an estimated 125,000 people, with 23,000 of those seated. This was felt to be more than enough capacity to satisfy demand.

But in an early and rare example of a football authority failing to believe its own hype, the FA had vastly underestimated the interest that had been drummed up for the game.

In the hours before Scorey and Billy began their own journey to the ground, a crowd at least twice the maximum capacity had set out for Wembley Park.

On the morning of the game, newspapers reported that 5,000 Bolton fans would be making their way from Lancashire to London, with expectations of 115,000 supporters from the capital and surrounding areas joining them in the stadium. The overwhelming mood was celebratory.

However, the mystique of the new ground, ease of getting to it by public transport and fine weather meant the FA's dream of a packed-out, perfectly staged showpiece quickly turned into a logistical nightmare for organisers.

A report, released in the aftermath by the stadium board of directors, lays out the bare facts.

The turnstiles were opened before 11:30am but within 90 minutes the pressure of the crowd began to tell.

At 1:45pm, with returns showing that all standing tickets had been sold, the gates were shut and London public transport informed that the stadium was full.

Fifteen minutes later, with people still arriving at Wembley Park to add to the huge crowds massed outside, a mounted force was requested from Scotland Yard - around the time Scorey went in search of that cup of tea in Westminster.

Around 2:15pm, the crowd broke through the barriers and began entering the ground, with an estimated 100,000 extra people making it inside.

It is known that 241,000 underground tickets to Wembley Park were sold that day. Some were fortunate to get a spot on a bus to the ground, thousands of others walked from central London.

Fans climbing the walls to gain access to the 1923 FA Cup final

Fans climbing the walls to gain access to the 1923 FA Cup final

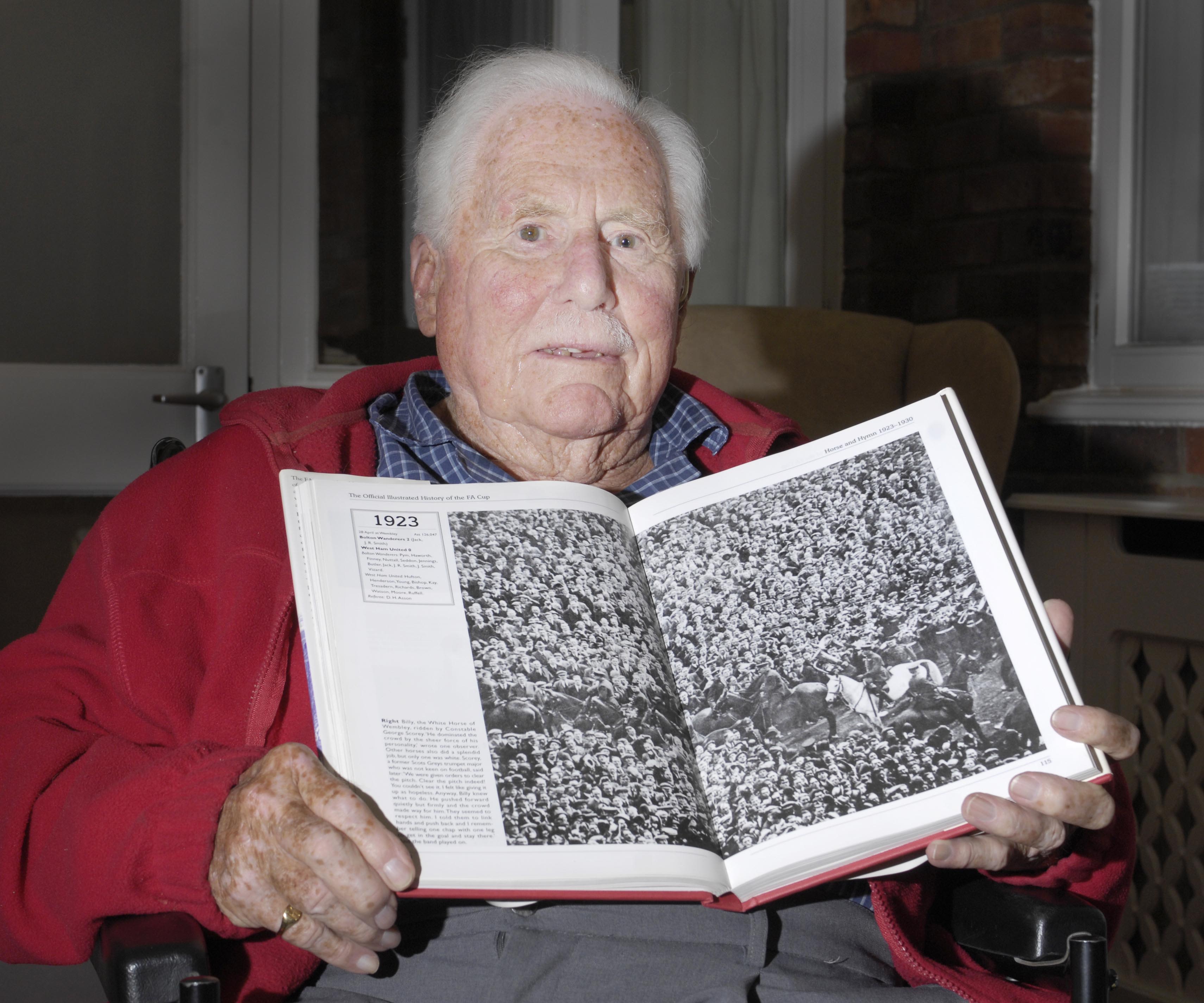

A proper sense of the day comes only from speaking to those who were there and in the very thick of the chaos. Sadly, none are still with us but we are fortunate to have testimony from a number of them, provided for Kicking and Screaming - a 1995 documentary series about football, shown on the BBC.

They speak to a day of high expectations and excitement, of danger and fear; one that brought a unique experience, with unexpected heroes and ultimately which became a showcase for civility and shared passion for the game.

Harry Beattie had just turned 21 and was lured to Wembley Park by the promise of the "marvellous new ground" - one that promised to accommodate all who wished to watch the game.

"My friend and I bought two tickets for the South Stand for this great match," he recalled. "I think they cost us about five shillings.

"The papers of course were giving it every inch of publicity they could and it was going to be an exciting day for us."

A teenage Doreen Prior had travelled to Woking to visit her family's former housekeeper, who suggested a trip to Wembley to satisfy the young Huddersfield fan's love for football.

"She knew I was keen on football and she suggested we went up to Wembley," Prior remembered. "She knew London very well and we went on the tube. It excited us.”

Dr Sydney Woodhouse was another fan in attendance that day.

"I think people got the impression that there'd be room for everybody," he said.

"There were five stations around the ground, rail and underground, and between them they were pouring people in at a tremendous rate between two and three in the afternoon.

"When we arrived at one of the Wembley stations we joined a solid mass of spectators moving towards the entrances.

"People were paying at that time. Those who had tickets were probably mostly in their seats, but thousands were arriving from the surrounds of Wembley between two and three."

Cyril Wilds, a Tottenham fan, said: “It was just a mass of people. I remember my father telling me when you get in a crowd to keep your hands at your side so you can protect your ribs. And always to walk on your toes because you would lose your shoes sometimes.”

One fan climbs a pipe to get access to the 1923 FA Cup final

One fan climbs a pipe to get access to the 1923 FA Cup final

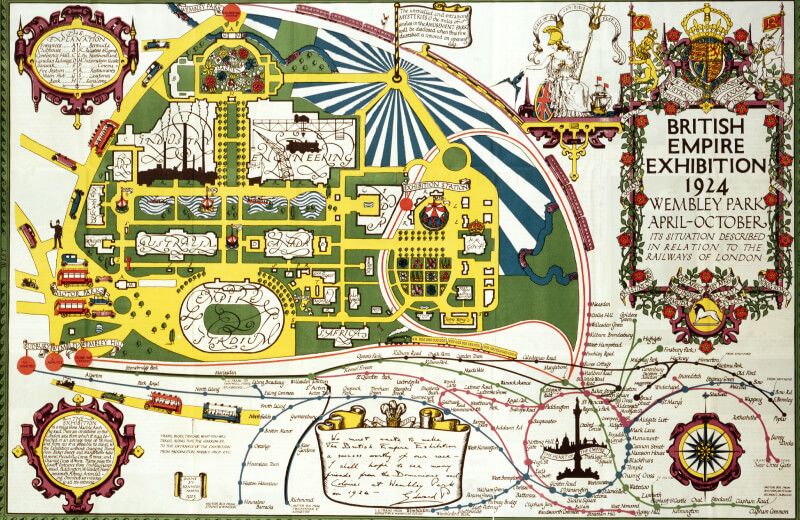

Dennis Higham was just eight years old on the day of the final. In 2007, aged 93, he spoke to BBC Sport’s Match of the Day about his experience.

"There wasn’t very much happening in the world in those days, but I do remember the great building [Wembley] that was going up," he said.

"My father said to me ‘I hear there is a good game this afternoon, let’s try and get in.’ He said: ‘I haven’t got a ticket but maybe we will be able to pay at the door.’

"We got a train from Harrow to Wembley and marched up that long Wembley Way, I think they call it now. When we eventually got up there it was a solid mass of crowd. We just couldn’t get any nearer. My dad, being fairly adventurous, said ‘look, I haven’t got a ticket and neither have they, so let’s try and climb in!’ So we did."

Dennis Higham, pictured in 2007

Dennis Higham, pictured in 2007

Not that many of them had the time or inclination to notice, but in among these supporters was a slightly unusual-looking West Ham fan sporting a moustache and glasses and carrying a suspiciously heavy-looking giant cardboard hammer.

News organisation Pathe had lost out to Topical Budget for the rights to film the 1923 final, but they were undeterred in their determination to get some footage on the ground.

The aforementioned "Hammers supporter" was in fact disguised cameraman Jack Cotter, wearing fake spectacles and a false moustache. Hidden within his cardboard hammer was a camera he used to capture some of the goings on outside the stadium.

Thanks to his cunning, we have some footage of the events, which you can watch on YouTube.

Rights holders Topical were smart enough, though, to have their name plastered across the roof of the stadium to ensure the aerial shots captured by Pathe came complete with the correct copyright.

Meanwhile, inside the stadium, things were getting hairy.

Reports after the game spoke to poor organisation and ill-prepared stewards, although it is hard to see how ready they could have been for the influx of so many people.

Unable to find space in the stands, people began spilling out on to the pitch. With kick-off rapidly approaching, there was barely a blade of grass visible, even to those who had shimmied up drainpipes outside the ground to get a vantage point from the roof of the stands.

“The place looked as though there had been a battlefield or something," recalled Beattie. "We saw people being rolled down over the heads of the crowd. Youngsters mostly I presume they were. They were getting rolled and rolled over and then put by a barrier at the bottom of the terraces.

"Then, very soon, the crowd went over as well, on to a cinder track. It was like waves of the sea coming in. Each wave went a little bit further. Then another wave would come and they'd go a bit further across the track. Then they were on to the green sward behind the goals."

Higham was separated from his dad in the chaos, but was fortunate to find assistance from others.

"I heard a voice behind me say ‘Oh, there is a young lad here, let’s take him in’,” he recalled.

"Another chap said ‘alright, pass him down the front’. I was carried over the top of all these friendly people and deposited somewhere near the pitch.”

Terry Hickey, speaking on BBC’s The Essential FA Cup Final in 1997, was far less calm in the melee.

“To be honest, I thought it was my lot," he said. "And I was only a young man then. I couldn’t see myself getting out. And then everybody started scrambling and invading the pitch, so I went with them."

With little sign of a game anytime soon and the pitch a sea of people with little idea of what to do next, Jack Mellor recalls the choir in attendance doing their bit to calm matters - singing one hymn in particular that would soon become a Wembley staple.

“When I looked about 10 minutes before kick-off you couldn’t see a blade of grass. It was only heads, people," he remembered.

"The choir of St Luke’s, to more or less pass the time on, they were singing Abide With Me. From then onwards it has always been at every cup final. It is part of the tradition now.”

Indeed, since 1927, the first and last verses of Abide With Me have been sung around 15 minutes prior to kick-off at FA Cup finals.

The choir were not the only body providing music as an attempted antidote to the madness of that day 100 years ago, as Beattie attests.

"In the centre of the crowd was a little ring, which looked like a dot to us from the distance," he said. "It was the red coats of the military band.

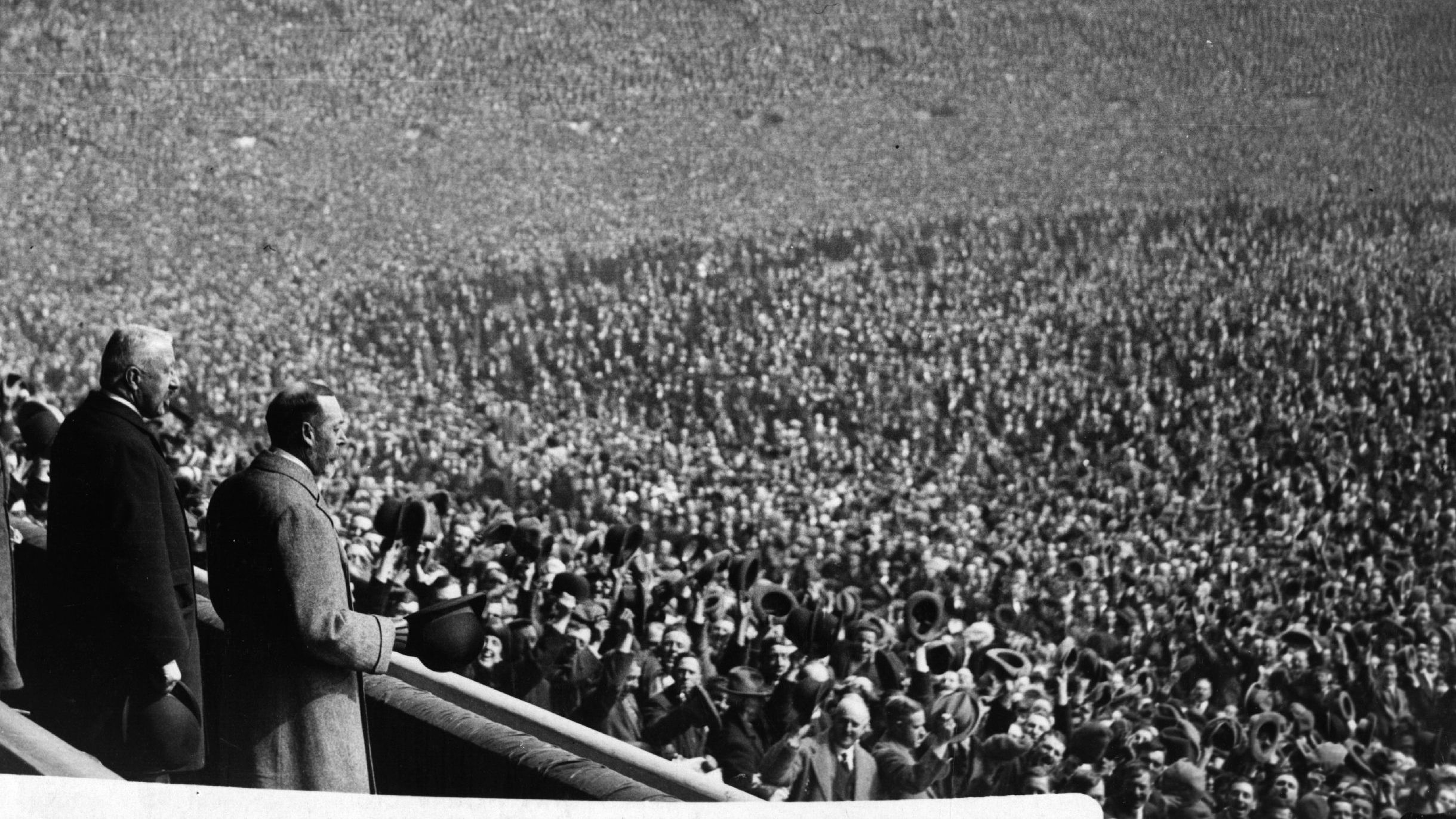

"The King was due to arrive before the match, and I think he arrived because the band played an anthem, and then they marched off and their place was immediately filled."

King George V had indeed arrived at the stadium. He would play a key role in averting disaster and ensuring the final went ahead, all without leaving his seat.

“It meant a lot to see the King and Queen because in those days the mystique was there," explained Wilds. "They didn't eat and drink, they were somehow different, and to see them go by and everybody taking their hat off.

"His presence helped. I think people thought ‘well, he is the head of the country here, we must do something’.”

Thankfully, they had some help from the boys in blue and their equine colleagues.

“The next thing was a policeman came on his white horse. I shall never, never forget that. It was a wonderful experience.”

Doreen Prior

The cavalry had arrived. Mounted police, with Scorey and Billy visible among their number, entered the stadium and just in the nick of time.

Players from both sides had entered the packed field to applause and plenty of back-slaps and handshakes from excited fans, but with the 3pm kick-off time having been and gone there was little sign (or seemingly chance) of the game starting.

As Wilds explained, the players themselves were far from immune to the greater concerns for the welfare of those in attendance.

"I was behind the goal," he said. "The West Ham goalkeeper was Ted Hufton, and he was in the goal area. Everybody was worried and there was one or two people he spoke to and I spoke to him.

"He said, 'I'm worried about my...' - I think he said his wife or his friends - 'that have come. I've looked up in the stand and I can't see them.'

"There must have been at least 5,000 people on the pitch."

A group of West Ham players find space among the crowds on the pitch at Wembley

A group of West Ham players find space among the crowds on the pitch at Wembley

Scorey and his colleagues set to work.

The man himself, in an extremely modest interview with the BBC, described what happened next.

“As my horse picked his way onto the field, I saw nothing but a sea of heads," explained Scorey. "I thought, 'We can't do it. It's impossible'. But I happened to see an opening near one of the goals and the horse was very good – easing them back with his nose and tail until we got a goalline cleared.

"I told them in front to join hands and heave and they went back step by step until we reached the line. Then they sat down and we went on like that.

"It was mainly due to the horse. He seemed to understand what was required of him. The other helpful thing was the good nature of the crowd.”

George Scorey and horse Billy get to work at the 1923 FA Cup final

George Scorey and horse Billy get to work at the 1923 FA Cup final

The general good nature of those in attendance is a theme to which many of those interviewed return. Unlike some of the violent and bad-natured scenes that accompanied the crashing of Wembley by fans ahead of the Euro 2020 final, the supporters on that day in 1923 were largely there just to witness and enjoy a big event.

This overwhelming desire was the root of the problem, but also a big factor in its solution.

“People were everywhere, in a horrible mess," said Higham. "In those days, nobody thought about crowd control.

"That number of people covering a football ground, that everybody wanted to see – that was the point that cleared them as much as the chap on the horse. They all realised that if they didn’t get off the pitch there wasn’t going to be a game.”

"Gradually, there began to be a filter of people going out of the ground," added Beattie. "They were coming and going as if the sluice-gates had been opened.

"I think it was due to the common sense of the people. They were there to see a football match, and they weren't going to see it while they were on the ground.

"It was hallowed territory really, and I think the pressure must have built from the centre outwards. After about half an hour they were right back to the touchlines. In fact, it formed a human rectangle in which play was to take place."

Within this arena, walled on all sides by a solid mass of people, play was finally able to begin, 40 minutes after the scheduled kick-off time.

The show must go on.

In keeping with the events of the day, the game began in frantic fashion.

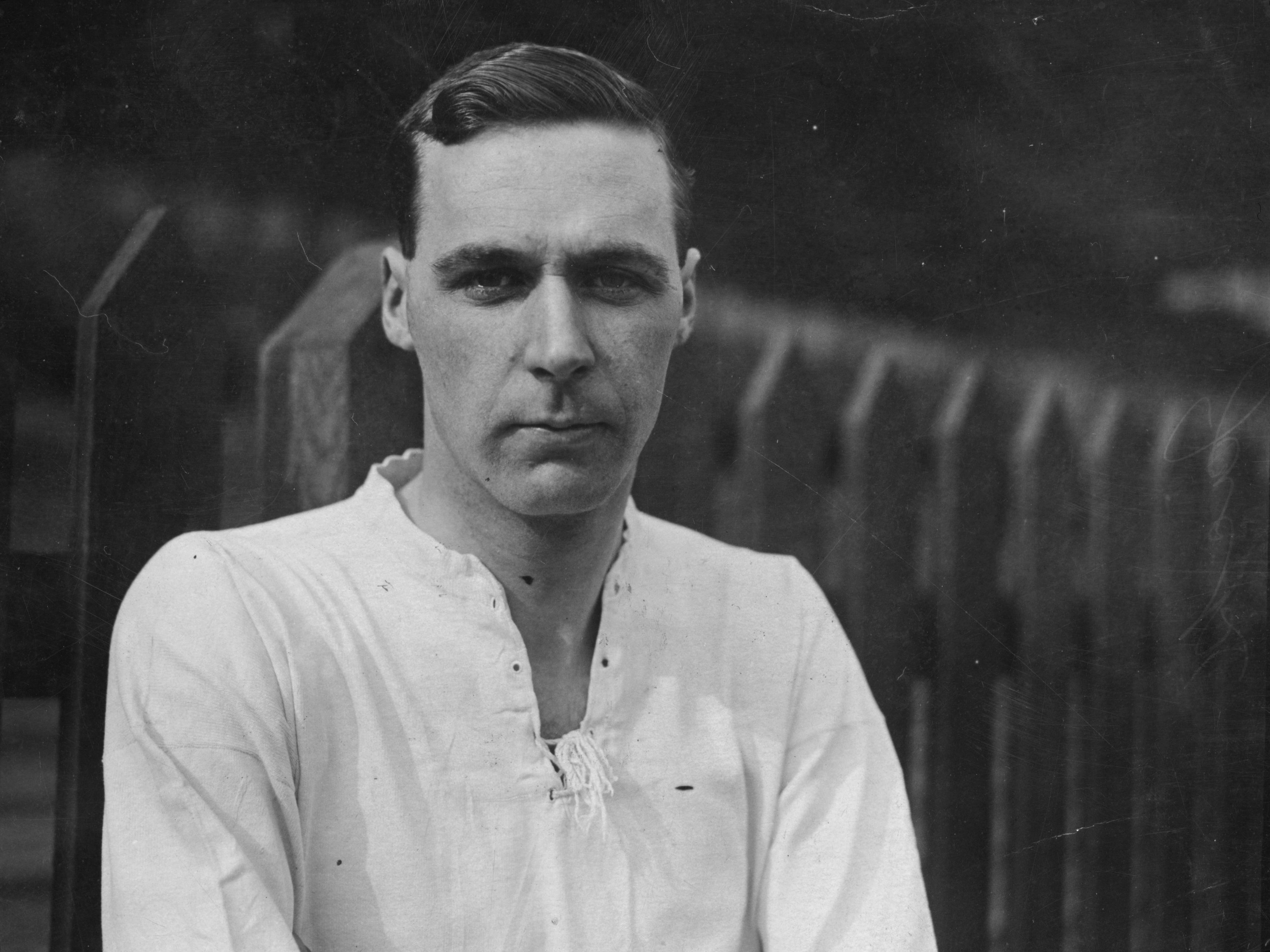

Just two minutes in, David Jack scored the first ever Wembley FA Cup final goal, continuing his scoring run for Bolton in that season's competition with his fourth strike in four games.

It came from a West Ham throw-in from Jack Tresadern which was intercepted by the Bolton forward, who then belted home a shot so fierce it gave no chance to Hammers keeper Hufton nor the supporters who had trampled down the netting behind him. One fan wore the shot with such force that he was thrust into those behind him, setting off a human domino effect.

Poor Tresadern could only watch on following his error, unable to fight his way back through the crowd to return to the pitch to make amends.

Jack's goal is just one of the acts that sealed his status as a Bolton legend. One of three brothers who all played pro football, he scored 144 times in 295 games for the Trotters before moving to Arsenal, becoming the first player transferred for more than £10,000 in the process.

With 113 goals in 181 subsequent appearances for the Gunners, he was the first and still one of only three players to score more than 100 English top-flight league goals for two different clubs, along with Jimmy Greaves and Alan Shearer.

Bolton's David Jack, pictured in 1923

Bolton's David Jack, pictured in 1923

Jack's would remain the only goal of a first half that lasted over an hour because of stoppages caused by sections of supporters being forced over the touchline and on to the pitch.

One particular incident, 11 minutes into the game, saw a lengthy delay because of fans encroaching on to the field and required the return of the mounted police and some medical care for some supporters.

Such close proximity of fans also added a layer of farce to proceedings.

"Touchlines were the human one," explained Beattie. "The ball bounced off them and went on.

"If it went over the top, it was a throw-in, but otherwise the referee got the game through. I think he did a good job under those circumstances."

Woodhouse added: "Even corners, when taken, had to be accommodated by forming a small corridor for the kicker to take a run outside the pitch in order to swing the ball inwards."

And there was the odd malicious interruption too. The game was played out with the added jeopardy for players of a leg being stuck out from the crowd as they ran past.

“I saw the wing man dashing down the wing and all of a sudden there is a foot stuck out and he goes head long," remembered West Ham fan Frank Bishop. "God knows how many occasions going around that touchline it happened, but I thought to myself ‘what a farce for a cup final’. But they carried through with it.”

Best seats in the house - fans watch the action from the touchline and stadium roof

Best seats in the house - fans watch the action from the touchline and stadium roof

Bolton were dominating and believed they had doubled their advantage when John Smith found the net in the 40th minute. However, a linesman's flag for offside put paid to that.

At half-time, with no access route available back to the changing rooms, the players had no option but to remain on the field for a five-minute break before the game resumed.

West Ham improved in the second half but Bolton crucially struck next when a cross from the left wing set up Smith for a volley that flew into the net and bounced out again. West Ham claimed the ball had struck the post but referee D.H. Asson felt differently, believing the ball had been propelled back by a supporter in the goal mouth.

Ted Vizard was officially given the assist although one fan also reportedly had a helping hand (or rather boot) by sticking out his limb to prevent the ball from going out of play as the Bolton player darted down the wing.

Smith is another man who carved his name into Bolton folklore. He was also part of the Wanderers side that won the FA Cup in 1926 and the first of three family generations to play for the club, preceding his son Jack Denver Smith and grandson Barry Smith.

West Ham's Billy Moore receives a pass from team-mate Jimmy Ruffell

West Ham's Billy Moore receives a pass from team-mate Jimmy Ruffell

Sensing the game was now beyond his side at 2-0, West Ham captain George Kay apparently asked referee Asson to call off the game in the second half. His request was met with short shrift, not least from Bolton skipper Joe Smith, who informed the official his side would "play until dark to finish the match if necessary".

Not long after, with victory secured, the Bolton captain and his team had to battle their way through another - albeit smaller – pitch invasion to make their way up the 39 steps to the Royal Box to be handed the trophy by the King.

Joe Smith would be back for another memorable final exactly 30 years later, as Blackpool manager for their Stanley Matthews-inspired 4-3 win over Wanderers.

Now all that remained was how everyone was going to get out of the ground and home. For some, that involved finding lost family and friends.

“My father came from Lancashire and so he obviously supported Bolton," recalled Higham. "I didn’t know at the time because I didn’t know where he was. All I could see was the occasional figure floating past.

"I was left down among the crowd, that were gradually wafting away. I thought to myself ‘well, I’ll never find him so I might as well stay here’. I don’t know how long it was but eventually he wandered into sight.”

Most drifted away quickly and quietly. Many Bolton fans remained to soak up the first major triumph in their history. It would be after 7pm before some could be coaxed down from the stadium roof.

Injuries were suffered that day, with some fans hospitalised - newspapers the next morning wrote of police helping to treat close to 1,000 casualties.

It was a miracle, though, that nobody was killed.

"I never remember seeing an ambulance or seeing anybody pass out from the crowd," recalled Woodhouse. "Had there not been free access to the pitch from the bottom of the terraces, the casualties would have been colossal.

"I think the crowd safety was due to the behaviour of the crowd and the absence of any barrier preventing people getting on to pitch. Otherwise I think hundreds would have been crushed."

The chaotic scenes were discussed in the House of Commons, during which police were praised for the way they handled the situation.

To try and prevent a repeat, recommendations were made to undertake alterations to the stadium to make it more robust in dealing with such large crowds.

More immediately, the FA had to refund £2,797 to ticket holders who were unable to take their seats. This from overall takings of a then whopping £27,776 - comfortably a record amount for a sporting event.

The next final was made all-ticket and it has remained that way since.

The events of the 1923 FA Cup final comprise one of English football's key foundational myths - a legend which has reverberated through the century since.

Wembley became ‘The Home of Football’, its turf hallowed, the twin towers akin to a holy shrine for fans of the beautiful game.

Pele, the greatest player the world has ever seen, said of the stadium: "It is the cathedral of football. It is the capital of football and it is the heart of football."

Even after its destruction in 2002 and resurrection on the same spot five years later - with an arch replacing the towers - the old Wembley lives on in hearts and minds. It remains the scene of England's greatest football high in 1966 and many more crushing lows.

What happened a century ago was a near disaster, yet has become cherished as part of the history of the national game. It is a story that speaks to English passion and pluck, to the nation's sense of civility, chivalry and sporting spirit.

Scorey and Billy are the tale’s unblemished heroes - ones that hark back to even more foundational myths of Englishness. They are the knight and his shining white steed, taming a dragon.

There is one small, awkward historical inaccuracy - Billy wasn't actually white.

The horse was in fact grey and a darkish grey at that. He stood out so prominently on the day because the other horses on duty were even darker, and then in photographs because they were overexposed as conditions that had gradually become more overcast.

When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

In honour of his role that day, Scorey would be offered tickets to every FA Cup final thereafter. He refused them all and never again attended a game.

When Manchester City and Manchester United run out for the 2023 FA Cup final, it will be in a different Wembley Stadium, built on the site of the original but at 1,000 times the cost (not adjusting for inflation).

However, thanks to a BBC Radio 5 Live poll conducted in 2005, the British public have ensured there will be a timely reminder of where it all began.

Much as the hordes of supporters did a century ago, fans will disembark at Wembley Park Station on 3 June. This time though, when they cross the railtracks, they will do so using... the White Horse Bridge.

Credits

Written and produced by Phil Dawkes

Sub-edited by Richard Dore

Images by Getty Images