Challenger, champion, change-maker

The real Lewis Hamilton story

Lewis Hamilton set the world on fire on his very first serious run in a Formula 1 car.

At Silverstone, in September 2006, a 21-year-old Hamilton was given an evaluation test by McLaren as the team pondered his promotion to F1 the following year.

McLaren’s then race driver Pedro de la Rosa was there as a benchmark. The engineers preparing the car knew Hamilton had talent - the team had been supporting his career for the past eight years - but they were expecting him, like most other drivers, to need time to adjust to the extreme demands of a grand prix car.

They were wrong. After a couple of familiarisation runs, Hamilton was given a set of new tyres, and immediately he was matching De la Rosa’s times.

“Just looking at the data for a couple of seconds,” De la Rosa recalls, “I realised we had a massive problem - me and all the other drivers on the grid.

“When I saw the strength of Lewis, I realised this guy is on a different level.”

The test team reported back to the factory that Hamilton was “incredible”, and before long his place in the team for 2007, as team-mate to double world champion Fernando Alonso, was confirmed. It was, says Martin Whitmarsh, McLaren’s chief executive officer at the time, “one of the easier decisions”.

Formula 1’s greatest debut season followed. Hamilton was unlucky not to win the title, but made amends a year later as one of the most dramatic finales in sporting history made him - at the time - the youngest ever F1 world champion.

Year after year, Hamilton has gone on producing moments that have been carved into F1 legend. Jaw-dropping qualifying laps and remarkable race drives continuing through the campaigns with McLaren and his later move to Mercedes, where he has not only dominated on track for the past seven years but become a global icon with a reach far beyond his sport. There have been a few controversies along the way, too.

According to many of those who have shared the journey with him, Hamilton is fair, generous, respectful, honest and honourable, but also ruthless, focused, self-obsessed and ultra-competitive; insular and intense but also warm and open.

And now, he is the most successful driver in the history of F1. He broke Michael Schumacher’s record of 91 wins last month, has equalled the German's record of seven world championships - and has every chance of adding an eighth next year.

This is how he did it.

Part one: The kart racer...

... unlike any other

Hamilton’s road to unprecedented success started at Rye House, an unassuming little go-kart track tucked between a supermarket distribution centre and a nature reserve at the junction of two railway lines just off the A10 in Hertfordshire.

It was there Hamilton went aged eight, with his father Anthony and a second-hand kart, and took his first step on to the motorsport ladder.

He immediately stood out. Not only because he was good - and he was - but because he did not look like any of the other kids he was racing.

Motor racing - like many sports that require financial input or attract the wealthier members of society - is notoriously undiverse. Formula 1 had never had a black driver.

Hamilton’s family were neither wealthy, nor white. His grandparents came to the UK from the Caribbean island of Grenada in the 1950s. Anthony grew up in west London, married a white woman, Carmen, and they had Lewis in January 1985, but spilt up when he was two.

Anthony lived in a council house in Stevenage and worked in IT for the railways. He took on extra jobs to supplement his income to find the money to support Lewis’s racing - selling double glazing, washing dishes, putting up ‘for sale’ boards for estate agents and so on.

“I had to buy a trailer to put the go-kart on and spare tyres, this, that and the other,” Anthony recalls.

“The credit cards were all maxed out.”

Money was not the only problem. The Hamiltons were usually the only black people at races, and there was racial abuse.

“The first time it happened,” a young Hamilton told the BBC at the time, “I felt really upset and told my mum and dad. I felt like I needed to get revenge, but lately, if anyone says anything to me, I just ignore them and get them back on the track.”

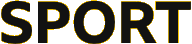

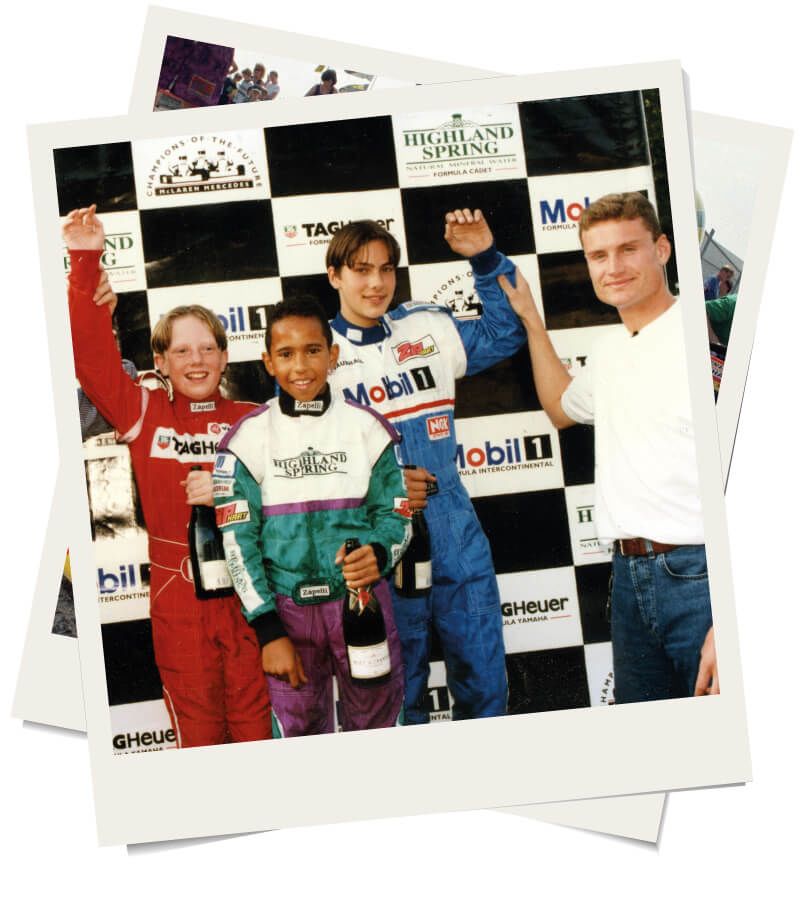

Aged 10, Hamilton became the youngest ever winner of the British cadet kart championship. That year, in 1995, he attended the Autosport Awards, the motorsport industry’s end-of-season shindig. He walked up to Ron Dennis, the boss of McLaren, introduced himself and said: “One day, I want to be racing your cars.”

Three years later, after Hamilton had won his second British kart championship, Dennis signed him up to McLaren’s driver development programme. Whitmarsh was put in charge of overseeing Hamilton’s career.

“He had this youthful, naive, warm personality about him. You wanted him to make it,” Whitmarsh recalls. “I don’t know whether I could have said back then that he was going to be a multiple world champion, you just saw that he was a really likeable kid who came from a modest background, had a pretty pushy father.

“He wasn’t arrogant or cocky. There are a few things he’s done in his life where from afar you think, ‘Oh, God, Lewis…’ but actually he’s not bad. He’s got a sincere humility about him. That lad came up and you thought, ‘There's something here. It’s got to be worth a punt.’”

Before long, success started to come - but not, at times, fast enough for either Hamilton or his father.

Hamilton won the UK Formula Renault Championship in 2003, and after finishing fourth in the Formula 3 Euroseries the following year, he and his father wanted to move straight up to GP2, then the final category before F1.

Whitmarsh disagreed. He thought Hamilton would learn more by staying in F3 and dominating the championship in 2005.

“We had a huge row,” Whitmarsh recalls. “I was accused of ruining his career by holding him back in F3. By that time, Lewis was getting a bit of traction and his father felt there were other options. In the end, I took the contract out and tore it up.

“I freed them. I said, ‘I don’t want you here under duress. We want to work with you. This is what I really want you to do. If you don’t want to do it…’

“It was about six weeks before Lewis rang me and we re-signed.

“I look back now and think, ‘I could have been the person who tore Lewis Hamilton’s contract up and never got him back.’ I was so lucky, really.”

Hamilton did what was asked of him, dominating European F3 in 2005 before moving up to GP2 in 2006 and driving one of the most impressive seasons the championship - now known as Formula 2 - has ever seen. F1 beckoned.

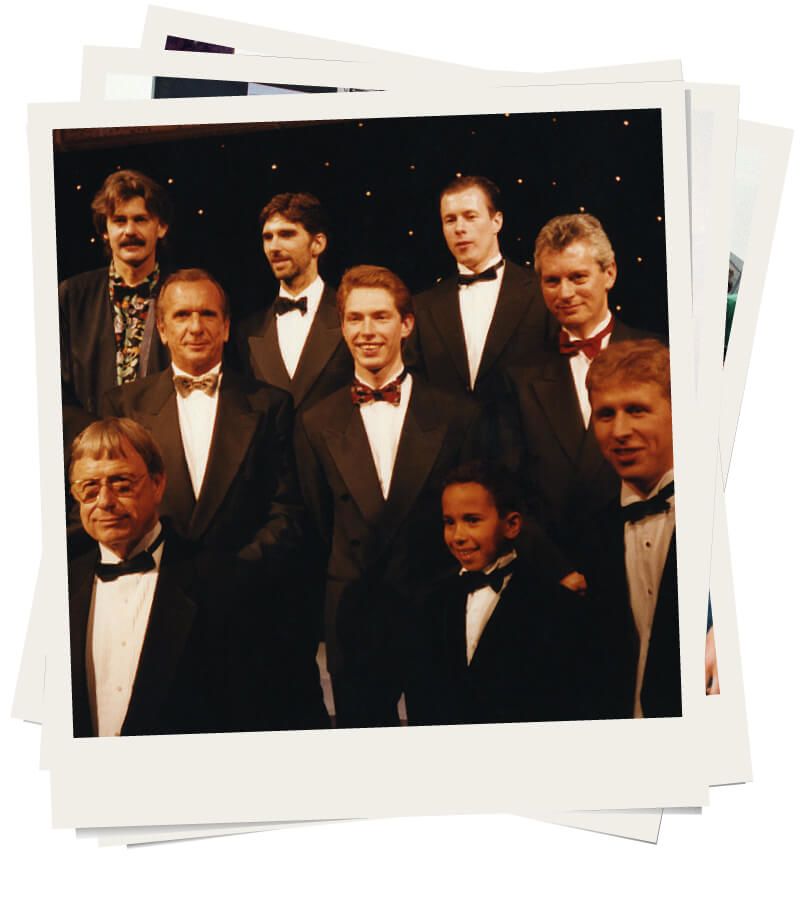

Alonso, who had joined McLaren for 2007 after winning two consecutive titles with Renault, was unimpressed when he was told his new team-mate would be a novice.

Whitmarsh says: “Fernando was, ‘Well, why are we doing that? If we’re going to try to win the championship, we don’t need a kid in the car, we need someone experienced. I need a strong team-mate; we don’t need a rookie.’ But it turned out to be quite a different story.”

What followed was a dramatic, tumultuous season in which arguably the strongest driver pairing ever put together in F1 came close to tearing McLaren apart.

Part two: Taking part...

... and taking over

Hamilton was on the podium for his first nine consecutive races, and won his seventh. The Italian media took to calling him ‘Il Fenomeno’ - the phenomenon. At McLaren, the tension was rising.

As the man who had ended Schumacher’s domination of F1 with Ferrari, Alonso had established himself as the sport’s leading driver. Although it wasn’t in his contract, the Spaniard felt his status demanded he be McLaren’s team leader and designated championship contender. Hamilton had other ideas.

At the first race of the season, Alonso qualified second and Hamilton fourth, but at the start Hamilton pulled a move that set the tone for what was to come. He passed his team-mate around the outside of the first corner and ran confidently ahead of him for two thirds of the race.

In the end, Alonso finished second behind Ferrari’s Kimi Raikkonen, with Hamilton third, but the ‘kid’ had left a huge impression. And it just kept growing.

“He turned out to be the best rookie there has ever been,” says Paddy Lowe, then McLaren’s technical director. “Because actually, more remarkable almost than seven championships and the most wins, his first half-season is just the most extraordinary in history.”

Hamilton first led the championship after the fourth race of the season, taking it away from Alonso at the Spaniard’s home grand prix. The problems that led to the team unravelling began at the next race in Monaco.

Alonso dominated the race from pole, building a sizeable lead over Hamilton. After both drivers had made their final pit stops, Alonso backed off to cruise to the end. Both had been told to be wary of overheating rear brake calipers.

But Hamilton closed up to his team-mate and started pressuring him. With a one-two in the bag, and no prospect of Hamilton passing Alonso, the team ordered Hamilton to slow down. He refused, and after the race made a point of revealing his disgruntlement to the world.

“It started to go wrong there,” Whitmarsh says. “Lewis should have on that occasion heeded the instructions of the team not to take excessive risk.

“But in fairness to him, he hadn’t had a win at that stage and he was hungry to have one.

“If he had been the subservient instruction-obeyer, he wouldn’t be the Lewis Hamilton who’s won seven world championships, would he?”

Hamilton’s maiden win did follow soon after, in dominant fashion at the very next race in Canada.

Through that long, tense summer, the advantage swung back and forth between him and Alonso, with Raikkonen and his Ferrari team-mate Felipe Massa also in the mix for the championship.

Adding to the pressure, the title battle took place against the political backdrop of the ‘spy-gate’ case, in which McLaren’s chief designer had been found in possession of 780 pages of confidential Ferrari technical information.

The next flashpoint was the Hungarian Grand Prix.

What was meant to happen was for Alonso to run first on track ahead of Hamilton during qualifying. McLaren had been alternating which of their drivers would benefit from a complex 2007 rule relating to fuel loads, and it was Alonso’s turn.

Instead, Hamilton went out ahead and refused repeated requests over the radio to let Alonso through. This put Alonso at a disadvantage in the fight for pole. Alonso worked out what was going on and made sure he came into the pits first before their final laps.

As Alonso’s new tyres were being fitted, Hamilton was waiting behind for his. With the work quickly finished, Alonso then held his car, having calculated how long he would need to block Hamilton to make sure he wouldn’t be able to start his final lap. When he was certain Hamilton was out of time, only then did he pull away.

All hell broke loose. Dennis threw his headphones down in disgust and went over to remonstrate with Alonso’s trainer, who he wrongly believed was involved. The drivers were called to the stewards, who also received a visit from Anthony Hamilton. Alonso was given a five-place grid penalty.

The next morning, still furious, Alonso met Dennis and threatened to go to the FIA with information pertaining to the spy-gate case unless the team disadvantaged Hamilton in the race.

Alonso later withdrew the threat, but it was too late. His relationship with McLaren was now irrevocably broken. A contract that had been meant to run for three years would be terminated by mutual consent at the end of the year.

“Lewis didn’t co-operate with the team or Fernando and that was straightforward disobeying,” Whitmarsh says. “He impetuously wanted to win.

“When thinking about signing a driver, having a daughter as I do, I’d think, ‘Would I be happy for my daughter to bring him home?’ If the answer was yes, you’d say, ‘OK, I don't think I want to sign him.'

“You wanted a driver who if your daughter brought them home, you’d think, ‘Oh, God, she’s going to get hurt,’ because they’re so selfish and self-possessed.

“As much as I love Lewis to death, would I be happy for my daughter to bring him home? No. As part of the complex equation of talent, intensity, focus, they also have to have a bit of ruthlessness.

“Lewis had that and he was bloody young. Would he be any different today? Probably not. And that was it, just bloody minded.”

Hamilton won that race, but finished off the podium in both Turkey and Belgium, either side of a second place behind Alonso in Italy.

A brilliant win in Japan followed, in torrential rain that caused Alonso to crash, and Hamilton went to the penultimate race in China with a chance of clinching the title in his debut season.

Instead, McLaren “just got it wrong”, in Whitmarsh’s words. Hamilton led from pole on a drying track, but the team left him out for too long on worn tyres. When he was finally called into the pits, tyres down to the canvas, he slid off the track in the pit lane and was beached in a gravel trap. Raikkonen won from Alonso. That left Hamilton leading the championship by four points from Alonso and seven from Raikkonen going into the decider in Brazil, in October 2007.

It should have been enough, but Hamilton’s hopes disintegrated. After qualifying second behind Massa, his first lap was messy. He lost places to Raikkonen and Alonso in the first couple of corners, then ran off the track trying to pass Alonso around the outside of Turn Four, dropping to eighth.

Hamilton was up to sixth within four laps, but then his car suffered a problem with a hydraulic valve. It was blocked for 25 seconds, during which time the car was stuck in fourth gear. The blockage flushed through but by then Hamilton had dropped to 18th place.

Massa dominated the race but Ferrari held him at his final pit stop long enough to gift Raikkonen the victory. It was just enough for the Finn to take the title, with Hamilton and Alonso one point behind.

Had Massa won, as he would have without team intervention, Hamilton would have been champion on results count back. With Raikkonen winning, Hamilton needed fifth place. He finished two positions short.

Looking back now, Hamilton says: "I remember the build-up to those races at the end and the pressure was there. That was not needed. If I knew then what I know now, I would have easily won that championship, I think. I have learnt not to add pressure that’s unnecessary."

The heartbreak of losing was countered by the knowledge that nobody had ever performed better in a debut season.

And everyone knew there was much more to come.

Part three: A first title...

... and many tests

A year later, Hamilton was back in Brazil, with another championship on the line, Sao Paulo native Massa his rival.

Memories of the championship slipping through their fingers a year before were still fresh and painful at McLaren. And then, at a public appearance the night before the race, someone threw a toy black cat on to the stage in front of Hamilton.

“It really spooked Lewis,” Whitmarsh recalls. “I remember going up to see him in his room on the Saturday night. Closing out the championship, after what had happened the year before… That was a time I felt we needed to be a little bit gentle and supportive.

“Most of the time, you didn’t need to - Lewis knew what he was capable of, and quietly had that self-belief.”

It was an agonising weekend. McLaren, knowing Hamilton needed only to finish fifth to clinch the title even if Massa won, took an overly conservative approach, Lowe admits. It led to one of the most spectacular finishes the sport has ever seen.

Hamilton qualified fourth and in damp conditions kept that position at the start as Massa led through two sets of pit stops on a drying track. Late in the race, there was more rain. Most of the drivers stopped for wet-weather tyres, but Toyota’s Timo Glock did not and that vaulted the German up the field, with Hamilton dropping to fifth.

The rain came down more heavily with two laps to go, and Hamilton ran wide, letting Sebastian Vettel’s Toro Rosso slip ahead into fifth place. Now the title was in Massa’s hands.

Hamilton fought to re-pass Vettel but couldn’t. As they went around the final lap, it appeared as if it was all over. Massa was about to win and Hamilton, one place short of the minimum result he needed, was on the verge of missing out for the second year in a row.

“I don’t know what Lewis was feeling in the car,” Lowe says, “but we just couldn’t believe we were having a repeat of the previous year. It was like, ‘God, what do we have to do around here to win a championship?’”

As Massa crossed the line, Hamilton was still sixth. In the Ferrari pit, they celebrated what they thought was the world championship. But out on track Glock was struggling in the wet on his worn slick tyres and Hamilton was catching, catching. He passed the Toyota as it slithered, gripless, out of the final corner, to take the fifth place he needed to clinch his first title.

As the celebrations abruptly halted in the Ferrari pit, at McLaren they went wild, Hamilton’s family - father Anthony, half-brother Nicolas and pop star girlfriend Nicole Scherzinger - with them.

“That was quite a moment for me and him and everybody in the team,” Lowe says. “For two minutes I was going to give up F1.”

Hamilton had made history, at the end of an up-and-down year that provided a number of standout moments. One in particular remains to this day one of his finest victories.

The British Grand Prix in 2008 was wet and Hamilton was out of this world, in a league way beyond anyone else on track that day.

As conditions ebbed and flowed, Hamilton was at times lapping five seconds faster than any other car. He won by a minute and eight seconds. Massa spun five times. Only two other drivers finished on the same lap. Hamilton’s team-mate, Heikki Kovalainen, who finished fifth, was not one of them.

It was a performance to compare with some of the greatest wet-weather drives in history - Jackie Stewart winning by four minutes at the Nurburgring in 1968; Ayrton Senna’s maiden victory in Portugal in 1985; Schumacher’s first win for Ferrari in Spain in 1996.

Hamilton has produced many similar performances over the years, where he is on another level beyond his rivals. How does he do it?

Driving an F1 car involves skills that most ordinary people find difficult to comprehend. After braking at the very latest point possible, the driver is balancing on the edge of adhesion at all times during cornering, in an exercise that could perhaps be likened to walking a tightrope at 100mph down a steep hill around a corner in high wind.

It is an activity that, in the words of Mercedes technical director James Allison, requires “sublime delicacy and unbelievable levels of concentration and precision”.

As McLaren’s test driver from 2007-9, De la Rosa witnessed Hamilton’s abilities closer than most. Having worked with both, he rates Hamilton and Alonso as the two best drivers he has ever seen first hand - including Schumacher.

Where they differentiate themselves from the rest, he says, is in the entry phase of a corner.

“Where they are special, Lewis and Fernando, is how much speed they can run into the apex and still have a decent exit speed,” he says. “It is very easy to say; it is very difficult to do.

“Most drivers, over one lap, when the rear tyres are at their peak grip, can do that. So if you look at [Hamilton’s current Mercedes team-mate Valtteri] Bottas, for example, over one lap many times he is matching Lewis.

“The problem comes when the rear tyres drop off. That’s when they are so much better than the rest. They still keep the speed going in.”

Lowe says an ability to control his car in this way not only “makes you go faster in the moment, but also allows you to set the car up to be nearer the limit, so it is inherently quicker”.

These skills also explain why Hamilton is often so much more effective in races than Bottas, when it comes to key techniques such as following another car closely, overtaking or keeping tyres in optimum condition.

“Some drivers cannot get that close to the car in front,” De la Rosa says. "But Lewis and Fernando, always, when they’re behind they’re nearly touching the gearbox.

“You can see they are following in a different manner, in an aggressive manner, in a way that is not comfortable at all for the car in front.

“You lose a lot of grip when you are following - especially with these modern F1 cars - but this type of driver knows how to compensate by balancing with speed and brakes.

“It doesn’t really matter if the car is understeering or oversteering, they will sort the balance out with their feeling. They don’t know why they are doing it. They just know it’s faster. And that’s all talent - pure, raw talent.”

Ability, though, is not all it takes to win in F1. If an inferior driver has an inherently superior car, there is nothing even someone as good as Hamilton can do about it.

Over the final four seasons of Hamilton’s time at McLaren, from 2009 to 2012, the machinery did not always match his standard, as Red Bull embarked on four years of domination with Vettel.

On top of that, Hamilton was growing up in the public eye, and personal problems at times affected his professional life.

In 2010, Hamilton told his father he no longer wanted him to be his manager, and the two didn’t speak for a while.

“It was the worst time of my life,” Anthony says. "It’s difficult to explain it. I think I probably was too much of an ogre. It was, ‘Lewis, do this, do that.’ And it was, ‘Come on, Dad, I’m a grown man.’

“That’s probably when he rebelled. He didn’t do it when he was 15. He did it when he was a world champion and it was all my fault because as a parent I forgot how to let go. And Lewis said, ‘Do you know what, Dad? I have to go and do my own thing.’”

Then, in early 2011, Hamilton split with Scherzinger. “He was very upset about that,” says Matt Bishop, then McLaren’s communications director. “He did love Nicole.”

Hamilton was destabilised, and in 2011 he made an uncharacteristic series of mistakes, many of them crashes with Massa.

At the time, it seemed that perhaps no incident better summed up Hamilton’s anguished state of mind than what happened in Monaco, where he finished sixth after being hit with two penalties for incidents during the race.

”It's an absolute frickin' joke," he said afterwards. "I've been to see the stewards five times out of six this season.”

Asked why he thought that was the case, he replied: “Maybe it's because I'm black. That's what Ali G says.”

The remark caused a storm. Chief steward Lars Osterlind and FIA president Jean Todt took offence at the implication Hamilton’s skin colour had been an influence in the decisions. For a while there was a chance Hamilton might be banned from a number of races.

In the end, McLaren officials convinced Hamilton to issue a statement saying he “never meant to offend anyone”, and the matter was quietly dropped.

Looking back through the prism of what Hamilton has become, the racial abuse he suffered early in his career, and the anti-racism stance he has taken this year, the incident takes on a different light. It’s clear now that the fact Hamilton is F1’s only black competitor has never been far from the front of his mind.

His Mercedes team boss Toto Wolff says:

“He asked me once, ‘Have you ever had the active thought that you are white?’ And I replied, ‘I have never thought about it.’ He said, ‘I think about it [the fact I’m black] every day.’

“That was a year or two ago, and it triggered a profound reflection within me, because we as a majority white people in European countries, you never think about it.

“Imagine you enter the paddock and you are the only white person and how difficult that would be. I guess it would make you think about your skin colour every day. And if you add abuse and racism to the whole equation, it becomes unbearable. This is what he and many others around the world are facing every day.”

Whitmarsh, who has been appointed as one of the members of the commission Hamilton has set up to look into the lack of diversity in the UK motorsport industry, points out that a very similar incident to Monaco 2011 almost happened at this year’s Russian Grand Prix, when Hamilton accused F1 bosses of “trying to stop me” after he was given a penalty for two illegal practice starts.

“One of the learnings I’m having right now,” Whitmarsh says, “is that I have gone through life not taking racism seriously enough. Because it hasn’t affected me; I haven’t witnessed it close hand.

“And I therefore do think that if you have experienced racism in your life at any point - and sadly if you’re black or not white in a predominantly white society, you have probably experienced it more than people realise - it must then subconsciously be in your mind as to why people appear to not be giving you the rub in critical situations.

“Lewis is super-competitive and super-ruthless. It really deeply hurts him if he doesn’t win the race on Sunday afternoon, and he is going to look for reasons - within himself, the team, the tyres, the officials, whatever. He is going to be looking for that reason because he has that passion, that strong desire, that will and that need to win.”

In the end, the lack of a second championship at McLaren got to Hamilton and he started looking for a move away. From early 2012, he was courted by Mercedes, then led by team boss Ross Brawn and commercial director Nick Fry.

At the time, McLaren had a faster car, and Mercedes had struggled in the three years since they took over the title-winning Brawn team at the end of 2009. Few expected Hamilton to make the jump. But jump he did.

At the time, Hamilton talked of needing a change, a fresh challenge and his belief in Mercedes’ chances of success in the future, and he gives the same reasons now. All of that was true, but there was more to the decision, too.

Late that summer, Hamilton had a massive falling out with Dennis, who had made some damaging personal accusations about his driver to Daimler boss Dieter Zetsche in a vain attempt to stop Mercedes signing him.

When Dennis’ actions made their way back to Hamilton via intermediaries, he was furious, and his relationship with Dennis was, in his mind, over. It remained that way for a long period; only in recent times have they extended olive branches to each other.

Hamilton, then aged 27, felt loyalty to McLaren, but much of him now wanted to get away.

Fry tells of an exhausting few days as negotiations over the detail of the Mercedes contract reached their critical point over the weekend of the Singapore Grand Prix, in September 2012.

Mercedes were initially some £3-4m short of the £30m fee Hamilton and his then manager Simon Fuller were demanding. They had to lean on title sponsor Petronas for more funds. There was a negotiation over the use of Hamilton’s image rights.

Hamilton led the race in his McLaren, only for his gearbox to fail, gifting victory to Vettel. He had a final meeting with Mercedes non-executive chairman Niki Lauda in his hotel room. By the end of the weekend, a deal had been put together on which all parties had agreed.

Hamilton flew to Thailand for a holiday before the next race in Japan. The contract was sent over to him from Mercedes via his lawyer, Sue Thackeray. There was silence for a few days. And then he made his decision. He called Whitmarsh to tell him he was leaving.

“That was one of the most difficult moments,” Hamilton says now. “I have been a very loyal person, I had been with McLaren since I was 13, so to decide to leave a team that had given me a place in the sport and to call your boss and tell them you’re leaving was damaging and emotionally difficult.”

Whitmarsh says: “He was very cosseted at McLaren, very controlled by two individuals he wanted to divorce himself from [his father and Dennis]. They had contributed to his growth but then ultimately limited his growth. I think he had the belief that he had to become his own man, and he had to be able to survive and grow further without those two dominant characters.

“It was the most difficult decision of his life. He was emotional about it. But at the time, I sensed it was the right decision for him, and subsequently it’s proven to be just that.”

Part four: A new home...

... domination...

... and personal evolution

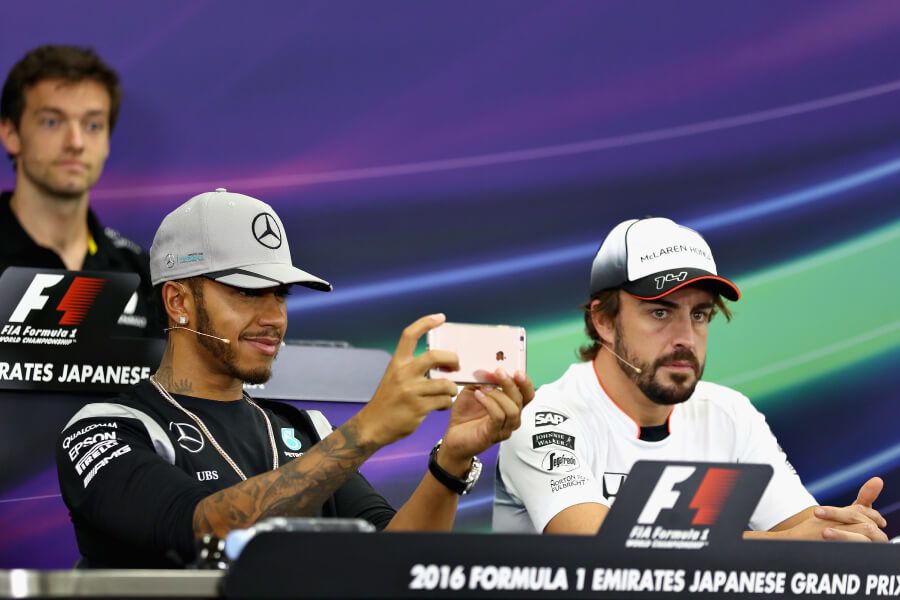

On a grey and humid Saturday afternoon at Japan’s Suzuka circuit, Hamilton’s 2016 championship hopes were unravelling before the world’s eyes.

A couple of hours before, his Mercedes team-mate Nico Rosberg had beaten him to pole position by 0.013 seconds. Now, the F1 media filed in to Mercedes’ base in the paddock to hear Hamilton’s thoughts.

They would hear them, but not in the way they expected. Hamilton made a short speech, in which he talked about a lack of respect, revealed his lack of enthusiasm for any questions, and walked out.

To explain why, we have to rewind a little.

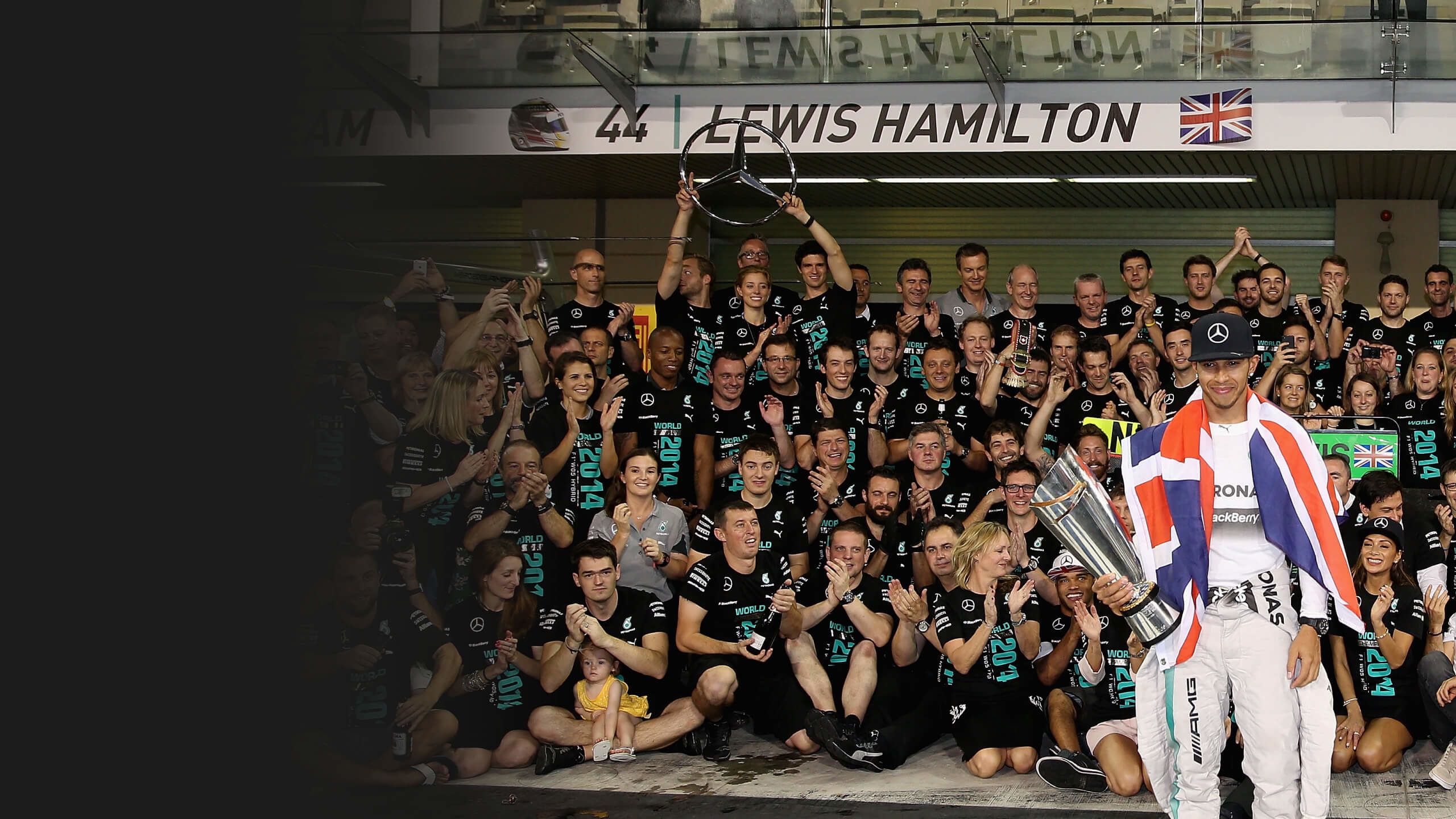

Hamilton’s move to Mercedes had paid off better and earlier than he ever expected. After a building year in 2013, the advent of F1’s hybrid engine regulations brought immediate success, and a car miles clear of the rest of the field. Hamilton won the championship in 2014 and 2015.

In 2014, he did it the hard way, three times overhauling a points advantage built up by Rosberg while Hamilton suffered problems. In 2015, he won his third title at a canter, dominating from the start and clinching the championship with three races to go.

It looked like there was no stopping him, but 2016 turned into a repeat of 2014 - only worse.

A bad start at the opening race of the season followed by engine failures in qualifying at two of the next three grands prix put Hamilton on the back foot, 43 points behind Rosberg after just four races.

Just as two years before, Hamilton clawed it back. There were hiccups along the way - a bad start here and there, an off weekend in Azerbaijan - but by late summer he was in the championship lead, only for a grid penalty at the Belgian Grand Prix, a legacy of earlier engine failures, to knock him back again. Then another difficult weekend for Hamilton in Singapore - where he just never seemed to get it together - put Rosberg back in front.

But as Hamilton led the next race in Malaysia, Singapore was behind him. Winning would give him a comfortable lead, one he was sure he could hold on to for the remainder of the year. And then his engine went bang. Again. “Oh no,” he screamed over the team radio, before kneeling down beside the smoking car, helmet in his hands.

Hamilton just couldn’t believe it. Why were all these problems happening to him? Not long after getting out of the car, he said to the television cameras:

“Something or someone doesn’t want me to win this year.”

Was he alluding to a conspiracy theory within Mercedes to allow Rosberg to win? An hour or so later, he clarified what he meant: “A higher power. It feels right now as if the man above or a higher power is intervening a little bit.”

A couple of days later, he took to Instagram with a series of posts praising the team. After arriving at Suzuka, he cut a distracted figure at the official news conference before the Japanese Grand Prix, refusing to engage with questions, repeatedly referring journalists back to his social media posts, and spending his time posting pictures of himself and fellow drivers on Snapchat using the animal-face filter.

The British newspapers were not impressed, and there followed a series of pieces criticising Hamilton’s behaviour. “Snap prat” was the headline in the Sun.

Shortly after the news conference, Rosberg bumped into a journalist, who informed him of what had gone on. “Did he?” said the German. “Good.”

Rosberg sensed an opportunity. The maths of the championship were clear - if he could win in Japan, he would have enough of a lead to finish second behind Hamilton at all the remaining races and still win the title. Which, given the size of Mercedes’ advantage over the field, should be relatively easy, reliability permitting.

Rosberg was fastest throughout the weekend, and just held off Hamilton for pole. Which brings us back to Hamilton’s post-session news conference.

“I’m not here to answer your questions, I’ve decided,” he said. “The other day was a super light-hearted thing, and if I was disrespectful to any of you guys, or if you felt I was disrespectful, it was honestly not the intention. It was just a little bit of fun. But what was more disrespectful was what was then written worldwide.

“I don’t really plan on sitting here many more times for these kind of things. So my apologies, and I hope you guys enjoy the rest of your weekend.”

The next day, before the race, Hamilton fussed over a damp patch on the track near his grid slot, and made a bad start, finishing only third behind Rosberg and Red Bull’s Max Verstappen.

Rosberg’s lead was out to 33 points and there were four races left. All Hamilton could do now was win them all, and hope that some misfortune befell Rosberg in one of them.

Hamilton did win them - but it wasn’t enough.

At the final race in Abu Dhabi, Hamilton made it difficult for his team-mate, putting him under pressure by backing him towards Vettel’s Ferrari, but Rosberg held on to seal the championship.

“I saw Nico when he got back to the garage and we were sort of out of sight,” Lowe says. “He just hugged me and burst into tears and said, ‘That was so terrible. It was so difficult.’ It was Lewis’s mastery of the situation, without being unsporting.”

After the race in Abu Dhabi, Hamilton wasted no time in pointing out that he had lost the championship because of the skewed reliability record between the two, but in the garage Lowe - who had moved to Mercedes at the same time as Hamilton - sensed his defeat would prove to be bad news for the rest of the grid.

“What he has learned and become better at, and now unbeatable because of, is to be always present at 110%,” Lowe says.

“I’m sure it’s a 10-year process. But 2016 was a very significant turning point.

“I remember at the time thinking, ‘Well, that’s just never going to happen again. Lewis is now unbeatable because he’s gonna turn up at maximum performance for every event.’”

That season finished Rosberg off. It had taken so much effort, focus and commitment to beat Hamilton to the championship, even with all the luck that had gone his way, using every trick he knew, on-track and off, psychological games and more, that he decided he couldn’t face going through it again. His lifetime ambition achieved, he quit at the end of the season.

Rosberg knew he wouldn’t beat Hamilton again. The question now was, who could?

Part five: The record-breaker...

... and the statesman

When he came back in 2017, with a new team-mate in Bottas, Hamilton never again brought up the engine failures and reliability issues when he was discussing 2016, only his own errors. A lesson had been learned, never to be forgotten.

Since then, his driving has risen to a new level.

The speed remains, now married to a new solidity and consistency. He has been unstoppable, even when he has not had the best equipment.

Hamilton has identified what he sees as his weaknesses - the bad starts and off weekends in 2016, the comparative struggles at times in qualifying of 2019 - and worked on them, while retaining all the strengths he has always had. It has become hard to pick any flaws in his game.

“His ability to question himself and to develop is really amazing,” Wolff says. “It is not something you see very often in champions.

“I guess many other people who become world champion or win a great title there are several risks - a sense of entitlement, a certain complacency which kicks in, which is perfectly understandable.

“The great champions don’t stop pushing themselves further and further and further. This is what I see from the driver Lewis Hamilton and from the person Lewis Hamilton.”

The driving force behind what Wolff calls this “relentless push for perfection” is Hamilton’s intense hatred of losing. His former team-mate De la Rosa saw it up close.

“Every winter we went to Finland for a week’s training camp,” De la Rosa recalls of their time together at McLaren. “He was so competitive, man. It’s unbelievable.

“No matter what sport we played, Lewis always had to win, and he was so good at everything. He’s just naturally talented for any sport. If we were climbing, he was the best from the team. Whatever we did, it was, ‘Man, Lewis again winning.’ It was a bit embarrassing.

“The only sport I beat him in was tennis. It was the only thing I have ever beaten Lewis at, and only in one game, because he realised he had no chance against me, so he never, ever wanted to play against me again.”

Mercedes chief engineer Andrew Shovlin adds: “You can’t ask Lewis to be happy when he’s lost a race; that’s not how he works. But he loses really well if you want someone to come back and win the next one.

“He’s actually better at losing than most I’ve seen because of how diligently he goes through the block of work of understanding what he needs to be better, where did he miss the opportunities. He doesn’t enjoy it, but it’s about the result at the next race, not whether he’s smiling or giving a nice interview.

“Lewis has natural talent in abundance, but his work ethic and ability to continually develop and improve means that, for drivers trying to beat him, he’s a bit of a moving target.

"The thing with Lewis now is his bad days are so few and far between and even on his bad days he’s as good as the others. That’s what’s brought him to the level he is. It’s the consistency. And when he’s at his best, the level is just phenomenal.”

Allison has worked alongside Schumacher, Alonso, Vettel and Hamilton in a 30-year career. He says: “Useless parlour game though it is, I personally think Lewis is the finest of them.

“As a racing car driver, I think he’s the fastest and most likely to win any championship between the world champions I’ve been lucky enough to work with.

“But it’s not just that. The thing I find remarkable about him is he’s as much of a carnivore as the rest of them in his dogged need to win. But he’s got a line, and it’s a line all the rest of us would want to admire in the way he handles himself as a sportsman and the way he interacts with us as a man. That’s what sets him apart in my mind and why I think I’ll always have a soft spot for him.”

The combination of the greatest F1 team ever assembled with one of the fastest and best drivers of all time, both of whom share an unquenchable desire to push on to the next level, has led to unprecedented levels of success at Mercedes. And the more Hamilton has had, the more he has had his eyes opened to what he can do with it.

Over the past few years, Hamilton has become increasingly vocal on causes that matter to him. It started with environmentalism, then veganism, which grew out of his concerns for the health of the planet. Then, as the death of George Floyd at the hands of US police sparked a global outcry in the summer of 2020, Hamilton found the voice to speak out on the horrors and injustices of racism, systemic and otherwise.

It has not been easy going. He has been central in F1’s decision to promote a pro-diversity agenda this year, but the messaging has left something to be desired.

The fact seven F1 drivers have chosen not to take the knee alongside Hamilton at the regular pre-race demonstrations, for example, has contrasted awkwardly with the more united message coming from athletes in sports such as football and basketball.

But Hamilton’s determination to speak out has not been affected, and he is not shy of pushing the message to a point where some feel uncomfortable, or feathers are ruffled, such as his decision to wear a T-shirt highlighting another case of police brutality, the killing of Breonna Taylor, on the podium at the Tuscan Grand Prix in September.

At the same time, he has won plaudits around the world for his stance on such important issues. Accompanying his naming as one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people of 2020 was a tribute from Nascar driver Bubba Wallace, the only black competitor in a form of motorsport with perhaps even more of a diversity problem than F1.

Wallace wrote that Hamilton’s “activism has moved the world”, adding: “Lewis’s mental preparation, his aura, his ability to capitalise on every opportunity to use his platform to drive out racism are more than just a model for race-car drivers and other athletes - he’s an inspiration for everyone."

Wolff says: “He’s almost philosophical about certain things. He spends a lot of time thinking. He is someone who hasn’t built his whole life on one particular pillar. It all circles around his driving. He is the F1 world champion. But now he is the F1 world champion and he’s a fighter for diversity, a fighter against racism. These are topics that go far beyond the racing driver.

“The topic of racism was always there and we discussed it. Every single year we discussed how we could increase the diversity within the team and he flagged that to me also - look at how many black people are in the team, it’s a super-minority and it is something none of us are really proud of.

“Starting with Colin Kaepernick and then the terrible killing of George Floyd, Black Lives Matter and the global movement to fight against racism, for somebody like Lewis Hamilton, with the visibility and recognition he gets from outside, he felt it was important to use his voice.

“Just trying to fight against racism in your closed environment wasn’t enough anymore. It was about raising your voice and changing the tonality as well, to make himself heard, to make racism a topic nobody could ignore any more, even if it polarises or it’s controversial. It’s just the right thing to do.”

Hamilton’s unwillingness to simply be an F1 driver rubs some people up the wrong way, and he receives criticism from various quarters for a number of different reasons - he’s too outspoken, he’s contrived, he’s too opinionated, too much of a poseur; whatever.

But those who have been close to him along the way paint a very different picture.

“We spent a lot of time together, travelling,” De la Rosa says. “I remember being in Malaysia testing after the race in 2007. We were having dinner and suddenly a British married couple was sitting next to us and they recognised Lewis.

“Back then, he was not really well known. They wanted to take a picture and he said: ‘Do you know me, or do you know Pedro?’ And they said, ‘No, no, we know you. We don’t know Pedro.’

“He was a bit surprised. He was so modest. He invited them to our table. We were having a coffee together and I am pretty sure for that married couple it was the best present for their honeymoon, you know?

“That was Lewis when he came into F1. He was truly refreshing. He was really nice. I’m not in contact with him on a regular basis now because I am not attending the races. But when I see him, I feel that it is the same Lewis, and he is the sweet boy I met when I was at McLaren and he was a kid.

“From the guy who was having dinner in Malaysia, he has changed. He would not do that now. But he has had to change. And that is what people have to understand.

“Lewis is one of the icons of sport worldwide, and that’s something we all have to accept. But his heart is in the right place, and his heart does not forget, and that’s really nice.”

Hamilton’s father says he still can’t quite believe what the boy from the council house in Stevenage has become.

“I sit in admiration and awe of Lewis for everything he has done,” Anthony Hamilton says.

“It’s a fantastic thing. I’m thinking, ‘Wow. You’re not just a race driver. You’ve become a statesman, a spokesman, a champion of causes for other people.’

“You shouldn’t be frightened to speak your mind. And what you see with Lewis is a young man, a son, who has a heart, who has feelings, who cares for other people.

“When I see people criticise him for whatever lifestyle he may have led, well, they don’t really know him. What they see is his public persona. They see that he has money, gold chains and other bits and pieces, but that’s nothing.

“What you see on the outside is not what people are; it’s what’s on the inside. And what’s on the inside is a young man who had a dream when he was eight years of age, worked hard, worked diligently, became the best in his field, honestly; is very kind, a very good son, a very good brother. And is enjoying life.”

Hamilton is 36 in January. His contract with Mercedes runs out at the end of this year, but while he said after the Emilia Romagna Grand Prix at the beginning of this month that there was “no guarantee” he will stay in F1, on the same day he also said that he wanted to “continue to make history together” with Mercedes.

So a new contract seems inevitable, and he will start next season as hot favourite to win an eighth world title and move even further clear in the record books.

“He is most aware he is a certain age where you can see the effects on performance,” Wolff says.

“But the way he is living his life, the way he looks after himself, the veganism, the training that is constantly adapting to his age, the people he surrounds himself with, all this makes it possible for him to stretch his ability for top performance beyond an age where you would normally think about ending your career. I think he has many more years in him to perform at the top level.”

Allison adds: “I hope his future is with us and glorious for a little while longer because it works for us and I know he enjoys being part of this.

“But he’s a person who is interesting and interested in lots of different things, and is sufficiently driven that I imagine he will pop up somewhere else doing something interesting.

“When he stops doing this - racing, that is - I very much doubt it will be the last the world hears of him.”

Credits

Author: Andrew Benson

Photo editor and producer: Philip Dawkes

Editor: Patrick Jennings

Sub-editor: Jamie Strickland

Photos: Getty Images, Rex Features, PA Images