Now you see her

A story about the competition no football club would host and the trailblazer it inspired

"But she ain't got a clue what she's doing."

The words jarred.

They have always jarred.

They still jar.

Sexist, offensive and disrespectful, but wholly predictable.

Sadly, Mary Phillip, England's first black international football captain and a six-time FA Cup winner, has got used to it, even now as manager of men's team Peckham Town.

"There was one game and the other team's managers turned up and they were like, 'she ain't gonna know the game'. They just proper ridiculed me before the match had even kicked off."

This is 2021.

"We ended up drumming the team," she says. "We annihilated them on the pitch that day - it was fantastic."

A centre-half with 65 international caps, revered for her speed and positional play, Phillip was the first Lioness selected for two World Cup squads - the first of which came when she was four months pregnant.

And her pioneering ways continued beyond a playing career inspired by the Women’s FA Cup, a competition largely dismissed and often ridiculed when the first final was taking place exactly 50 years ago.

After retiring in 2008, Phillip went into coaching and just last year became the first female manager in the UK to lead a senior men's team to silverware at any level, winning the London FA Trophy with Peckham.

"Among Peckham players my gender has never been an issue but opposition teams often mistake me for the physio or a player's girlfriend," adds Phillip.

"It is still perceived as a men's game and I am in men's football. But when you learn to play you are coached the exact same way a man is. The drills and tactics are the same."

Peckham are some way off FA Cup glory, but Phillip's own football journey is inextricably linked with the competition that first roused her into thinking football could be her future.

"I was born in the 70s, fell in love with the game in the 80s, played at elite level in the 90s, became a professional in the early 2000s and a manager in the 2010s," says Phillip.

The FA Cup was central both to her journey and the game's growth.

From a once barely acknowledged event played on a bumpy pitch surrounded by an athletics track, the final has developed into a showpiece occasion beneath Wembley's famous arch, watched by more than 40,000 fans inside the stadium and two million more on television.

Since that first final was held at Crystal Palace on 9 May 1971, the whole sport has changed beyond all recognition. And so have the players - from amateurs competing in parks to household names seen all around the world.

Without the Women's FA Cup, there would have been no Women's National League and consequently no fully professional Women's Super League, now capable of attracting multi-million-pound TV deals.

At 14, Phillip caught a glimpse of people of her own gender kicking a ball about on the television for the first time.

This was 1991.

It would change her life.

In the 1990s, the top level of women's football was still some way off the standard of today. But women had to fight extraordinary prejudice just for the right to play.

The women's game first became popular during World War One, but men remained hostile.

Football Association council member John Lewis, who refereed a match, was far from alone in thinking it was "not a game suitable for women, and if they continue to play during the war I hope they will cease doing so when the peace is declared".

He got his way. Women's football was banned in 1921.

Almost half a century on, 19-year-old Patricia Gregory was with her dad at Tottenham Town Hall to watch Spurs bring home the FA Cup after beating Chelsea in the 1967 final. She realised she had never seen women play, so she wrote to a newspaper to ask why. Several girls responded, eager to join her club.

Gregory didn't have a team, so she set one up and called it White Ribbon.

After she advertised for opposition, a carpenter in Kent called Arthur Hobbs got in touch to tell her about an unaffiliated tournament he ran.

Four years before the Women's FA Cup was launched, air stewardesses were being tasked with modelling kits for the men's World Cup in England.

Four years before the Women's FA Cup was launched, air stewardesses were being tasked with modelling kits for the men's World Cup in England.

There were difficulties, with the FA ban meaning women couldn't hire council pitches or book qualified referees.

But Hobbs' 'Deal Tournament' quickly grew in popularity. In 1969, 47 teams entered and almost unanimously agreed to form the Women's Football Association.

Hobbs and Gregory were among the founding board members.

The FA wrote to the WFA at the turn of 1969-70 to say it had agreed to overturn the ban.

A fledgling national cup followed in November 1970, steadily flourishing ever since to become the Women’s FA Cup we recognise today.

The inaugural WFA Cup was known as the Mitre Challenge Trophy by virtue of a hard-won sponsorship deal with the sportswear manufacturer.

Progress was being made, but in baby steps, not leaps and bounds. By 1971, women were no longer banned, but neither were they welcome.

It was into this 'men only' society that Phillip was born in 1977.

She grew up in Peckham, south east London, where she still lives today. Her father was a bus driver and her mother a primary school teacher. Phillip's time was devoted to the sport she adored.

"Every weekend, every evening, I would have a kickabout with my mates," she says. "Mainly boys but some girls too.

"When we had a break, we would walk up what we called 'Juice Hill' to drink our juice and from there you could see into The Den. You could see Teddy Sheringham and Tony Cascarino playing for Millwall."

Seeing television highlights in 1991 and discovering that Millwall had a women's team too, and there was a cup final for women, "meant everything" to Phillip.

She says: "I always got told 'girls shouldn't be playing football', 'you won't get anywhere in sport' and 'you've got to be a secretary or something like that'."

The naysayers were never going to win.

"It's a passion within that makes you want to achieve something," says Phillip.

Growing up in a multicultural area in a stable family environment helped her tremendously. She simply wasn't aware of some of the barriers so many - including her mum and dad - have encountered.

But, she knows that as a mixed-race couple, her parents had a tough time raising a family in 1970s Britain.

"They don't talk to us too much about it," she says, "but when they got together, you still had signs up saying 'No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs'.

"Well, mum was an Irish woman, dad was black and they had a dog, so they had the full package.

"The sheer fact they are still together in 2021 proves that if you don't let the negativity of people get to you, you can move through things.

"You don't ignore everything, or just accept it, but you don't let it dictate how you are going to live your life.

"I'm black, my brother is white. We've got the same mum and dad.

"I don't think of my brother as white; he doesn't think of me as black. I think of him as my brother. I've just never worried about people's race or gender."

The generation that preceded Phillip's faced even greater prejudice.

Six years before she was born - and just 15 minutes from where she lives in Peckham - that first Women's FA Cup final took place.

Southampton won 4-1 against Scottish side Stewarton Thistle, now known as Kilmarnock, at the Crystal Palace National Sports Centre.

Surviving footage shows grass so long it was more suited to grazing sheep than playing football. But it was a start.

Six years before she was born - and just 15 minutes from where she lives in Peckham - that first Women's FA Cup final took place.

Southampton won 4-1 against Scottish side Stewarton Thistle, now known as Kilmarnock, at the Crystal Palace National Sports Centre.

Surviving footage shows grass so long it was more suited to grazing sheep than playing football. But it was a start.

Coverage and exposure remained limited, condescending and generally full of double entendres. Rare was the male reporter in the 1970s who could resist referring to any error as "a boob".

Phillip isn't surprised when told about how the game was covered back then.

"It's pure ignorance," she says. "Men could just go out and say what they wanted and everyone would agree.

"It still happens, although a lot more men realise it isn't acceptable and there are more male allies."

While the sniggers and sniffy tone remained in the FA Cup's early years, the WFA was at least able to play on non-league grounds.

It took 11 years until a Football League club agreed to let the novelty, nomadic competition take place on their sacred turf.

However, the fact that the most prestigious women's football match was consigned to one of the least popular playing surfaces in the country perhaps tells its own story.

The plastic pitch at Loftus Road was much maligned.

The plastic pitch at Loftus Road was much maligned.

QPR's Loftus Road was notorious for its plastic pitch, feared and despised by visiting teams. In west London, Lowestoft beat Cleveland Spartans - now Middlesbrough Women - 2-0 in the 1982 final.

Because sportswear was made mainly with men in mind, Cleveland had no Astro boots and Lowestoft couldn't find any to fit.

They ran around in oversized men's boots with newspaper stuffed inside. At least the scrunched-up newspaper served a purpose.

The Fleet Street coverage was written exclusively through male eyes. One preview read:

"Twenty-two pairs of well-formed ankles will trip out for the cup final."

Another: "All the Cleveland girls are single".

Linda Curl, who scored in Lowestoft's victory, was described in one match report as "shapely".

"The national papers were like that," says Curl, who to this day remains England's youngest female international, having made her debut as a 15-year-old in 1977.

"It is a bit strange looking back but that attitude was so ingrained in society at the time that you just accepted it."

The 1991 highlights programme on Channel 4 was the first television coverage to register with Phillip, but there had already been some - albeit fleeting - exposure.

The BBC first broadcast the men's FA Cup final in 1938. It was another 64 years before the women's competition was shown live on terrestrial television.

The BBC first broadcast the men's FA Cup final in 1938. It was another 64 years before the women's competition was shown live on terrestrial television.

In the 1970s, the goals from the final were occasionally played into Cup Final Grandstand and the following decade, at a push, you might catch a brief report on the BBC's Breakfast Time or ITV's TV-am the following day.

When the men’s FA Cup final took place, almost the entire day’s output on BBC One was dedicated to the match. From the 1970s through to the late 1990s, it felt like a national event - and television lapped it up.

Channel 4 did, in fact, broadcast the first dedicated women's FA Cup highlights show two years prior to the programme Phillip viewed as a 14-year-old. They were rewarded with a five-goal thriller as Leasowe Pacific, who morphed into the present-day Everton, beat Friends of Fulham at Old Trafford.

The following year, the channel showed highlights again as Doncaster Belles beat Friends of Fulham 1-0 at Derby County's old Baseball Ground thanks to a fabulous winner from Gillian Coultard.

Coultard won 119 caps for England, scoring 30 times.

Coultard won 119 caps for England, scoring 30 times.

If you could only name one women's footballer in the late 1980s or early 1990s, it would likely be Coultard.

She was a genuine superstar, only a few curls of hair above 5ft tall but always a towering, effervescent presence.

Creative, technically outstanding and a modest leader, Coultard would go on to become the first woman to win 100 caps for England and lifted the FA Cup five times with Doncaster Belles.

Her talents made quite the impression on Phillip, long before they became international team-mates.

"I always remember her and Lou Waller of Millwall in the middle," Phillip says. "I didn't know their names but I was watching them, their passing and the battle that went on.

"It is not the same as you'd see today but those are the little memories I have of women playing football.

"They were playing football to the standard that you were going to sit and watch."

Visibility was growing but, shamefully, secondary schools did not cater for girls' football.

With so few women's clubs around, many saw their passion for playing snuffed out in their teens.

The early years of the cup were dominated by Southampton, who won eight of the first 11 competitions. Two of those came against QPR in 1976 and 1978 but QPR won 1-0 in 1977.

One of the goals in the 1976 final was a stunning free-kick scored by QPR's Paddy McGroarty, who had spent time as a nun prior to her footballing days. It was a peach of an effort with the outside of her right boot that went in off the far post.

Yet you've probably never seen it.

Nor will you have witnessed Alison Leatherbarrow's magnificent curling effort into the top corner for Fodens in 1974, Hilary Carter's fierce shot for Southampton in 1981, the screamer with which Sheila Stocks (later Edmunds) put Doncaster ahead in 1983, nor Coultard's own effort in 1990.

Men's goals in the same competition, over the same period, transcend generations.

From Ricky Villa's mazy dribble in 1981 to Steven Gerrard's dramatic thunderbolt for Liverpool in 2006 and many in between, before and after.

By the late 1980s Coultard's Doncaster had assumed Southampton's mantle as the strongest team in the land. They reached all but one of the 12 finals played between 1983 and 1994, winning six.

League football remained regionalised until the introduction of a Women's National League in 1991-92. While the early rounds were often organised geographically, the latter stages of the FA Cup provided a chance for the country's top teams to meet.

"The final meant everything," Coultard says. "It was the only time the media or any of the public paid any attention. It was the only time you would take on the other truly great players and teams."

In 1991, Coultard was among the players on show in the final as Phillip watched on from her living room.

It was a chance encounter with a youth worker that opened the door to Phillip's own playing career.

"I was just throwing a ball around with my friend in the street, not even kicking it, just throwing it, and this youth worker called Audrey spotted us," Phillip explains. "She asked if we liked football and if we'd want to play for the girls' team at Patmore Road Youth Club in Wandsworth."

To get the opportunity to play with other girls meant a trip from south east to south west London three times a week, as well as at weekends for matches.

"I am so grateful to Audrey and to my dad. He wasn't really a football man," says Phillip. "He loved his cricket, snooker and boxing."

As Phillip watched the 1991 final in awe, among the Millwall players celebrating on screen was a woman who would soon become a team-mate and one day also her England manager - Hope Powell.

"I learned so much from Hope," says Phillip. "Hope was one of the older heads.

"Training at Millwall was really disciplined," adds Phillip. "It felt organised, it felt challenging. I'd never have got my England chance without that grounding."

Phillip's England chance arrived in 1995 - but that wasn't to be the only arrival that year.

Aged 18, and four years after the 1991 television coverage fomented her love for the game, she became pregnant.

She'd already been to a World Cup by the time she found out.

"I didn't know I was pregnant with my first child when I went to the World Cup in 1995," Phillip says.

"I was ignorant to the changes I was going through and thought it might just be that I was training so hard to get in the squad."

Phillip describes the support she got from Millwall Lionesses when she discovered she was pregnant as "fantastic".

"I trained up to eight and a half months," she adds. "The club were so open to me coming in and working. I was doing simple ball work and running.

"I was about four months pregnant at the World Cup. I wasn't showing at all.

"I was doing cartwheels and roly-polies and everything we were doing for our training drills.

"Every pregnancy is different. Some people get terrible sickness all the way though. I was very lucky and had a straightforward one. When it's like that, the female body is amazing. You can do stuff when you are pregnant and your body adapts to you.

"I didn't make it off the bench in Sweden but just being part of the camp, taking in what went on, experiencing the big-tournament atmosphere was all so important.

Katie Chapman helped England finish third at the 2015 World Cup.

Katie Chapman helped England finish third at the 2015 World Cup.

"I know later on in my England career, Katie Chapman had three children while playing, but other than that I can't tell you another female footballer who has had children and played at elite standard in England.

"Many people said I wouldn't be able to play football and be a mum, that it had to be one or the other. People said I had a big decision to make but I couldn't see why I couldn't tie it all together.

"There is a lack of understanding about how much some women can do.

"When I had my first child at 18, I was told I wasn't going to play football and that was my career done, but I proved people wrong.

"When I had my second child at 22, I was being told 'you're never getting back into the England squad, you can forget about that'. But I not only came back, I also became captain."

"After a child, your life doesn't have to stop."

By the mid-to-late 1990s, the women's football landscape was changing.

The first Women's FA Cup final Phillip played in - in 1997 - looked and felt different to the first one she watched in 1991.

There had been three key changes.

First came the creation of the Women's National League in 1991-92. And then the WFA handed over the running of women's football to the FA prior to the 1993-94 season, which ended with the first final to be televised live.

Sky showed it as part of the build-up to their Super Sunday offering of Blackburn v QPR in the Premier League (or Premiership as it was then known).

Coultard's Doncaster won 1-0 against Knowsley United, who became Liverpool Ladies within weeks of the final.

UK Living later stepped in as tournament sponsors and televised the 1997 final 'as-live' on the evening of the game.

That year, Phillip and her Millwall Lionesses team-mates stepped out in front of 3,000 fans at Upton Park - home of West Ham United.

They were 1-0 winners over Wembley, who evolved into the present-day London Bees.

"It felt like a real occasion," says Phillip. "To be in a men's Premier League stadium and to go out on the field and for there to be people there who weren't just your mum and dad.

"My main memory is of being in the dressing room afterwards and my first born Jordan, who was two by then, being on one of the girl's shoulders as we all jumped around singing a song that was really popular at the time - How Bizarre by OMC.

"That song became our anthem because of just how mad things seemed to be at the club at that time."

Chapman was in the Millwall Lionesses midfield that day - aged just 14.

By the time she retired in 2018, Chapman had won the FA Cup with five different clubs, played in seven victorious finals and become the first captain to lift the trophy at Wembley with Chelsea in 2015. And, like Phillip, she had proved you could do it having had children.

In 2000, Chapman and Phillip embarked on another adventure together when they were among the first 16 women players in England to turn professional.

That year, the FA voiced ambitions of establishing a women's professional league within three years.

When it failed to materialise, an FA spokesperson explained why...

"We've come a long way in women's football but we're a participation sport, not a spectator sport.

"We have looked into the viability of a professional league but we have no date set."

That date for a professional league, it turns out, was 2018.

But, some 18 years previously, Fulham owner Mohamed Al Fayed, fresh from having bankrolled the club's return to the top flight in the men's game, set up the first professional women's team in Europe.

Chapman asked Phillip to join in for a trial, because Fulham were looking for defenders.

"The contract I was offered was £16,000 a year," Phillip recalls. "I could have made more working in my local supermarket but how could you possibly turn down the chance to be a professional footballer?

Mohamed Al Fayed took over at Fulham in 1997.

Mohamed Al Fayed took over at Fulham in 1997.

"It also made my life a lot easier. You would go to training for 10 and get home by five and it was still daylight. I had time with my young children before bed time.

"The three years at Fulham were amazing."

Despite being the only professional team in Europe, Fulham were in the third tier in 2000-01 and had to work their way up to the National League.

Women's football royalty in the form of Norway's 2000 Olympic gold medal winners Margunn Haugenes and Marianne Pettersen joined the revolution.

Double figures were often reached as opponents were swatted aside on the way to promotion. Their only real tests came during the FA Cup, in which they reached the 2001 final to take on the mighty Arsenal.

The Gunners had followed Southampton and Doncaster in dominating the women's game. They started the 2000-01 season having already won three league titles and four FA Cups and ended it with the second treble in their history.

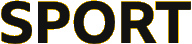

Fulham, with Katie Chapman at the heart of their midfield, took on Arsenal in the 2001 final.

Fulham, with Katie Chapman at the heart of their midfield, took on Arsenal in the 2001 final.

There has quite possibly never been a national cup final anywhere in the world in which the underdogs, in terms of league placing, could also be regarded as favourites. Fulham's professional status meant that was what they were in the eyes of many.

A competition record of 13,000 were watching at Selhurst Park with the final now back live on Sky.

Fulham lost 1-0 to an Angela Banks goal. It might have been different had Haugenes not seen her penalty saved by Emma Byrne just before Banks struck.

"At the time, losing that final was the biggest disappointment in my career because of the hype and massive crowd," says Phillip. "It was a cruel way to lose, but it galvanised us.

"Turning pain into determination for better days is one of the most important things you need to learn in football."

In 2002, Fulham and Phillip were back in the final, this time as a second-tier side.

The match was at Selhurst Park again and Fulham were once more favourites against an amateur team from the division above, Doncaster.

In the first final to be shown live on terrestrial television, Rachel Yankey's superb free-kick helped the Cottagers to a 2-1 victory.

It felt as if women's football had finally reached the big time.

In 2002, Fulham and Phillip were back in the final, this time as a second-tier side.

The match was at Selhurst Park again and Fulham were once more favourites against an amateur team from the division above, Doncaster.

In the first final to be shown live on terrestrial television, Rachel Yankey's superb free-kick helped the Cottagers to a 2-1 victory.

It felt as if women's football had finally reached the big time.

At the time, the significance of the mainstream exposure on BBC One was lost on Phillip and her team-mates.

"We just wanted to win it because of what had happened the year before," she recalls.

"It was probably only after, when people started getting recognised walking to the shops, that we realised the game had a big impact."

Prior to the 2002 final, women's football had also hit the mainstream with the recent release of Bend it Like Beckham in British cinemas.

The romantic comedy charts the struggle of a young British Indian Sikh woman who pursues her love of playing football despite the disapproval of her parents.

The goal with which Fulham took the lead was a case of Bend It Like Yankey, who would hang up her boots in 2016 having won the cup a record 11 times.

"That goal was straight out of the Beckham textbook," says Phillip.

"The funny thing is that we were actually in Bend it Like Beckham too. They used Fulham as one of the opposition teams and at the end of the film in the credits they showed us all dancing."

Fulham's players would be dancing again that season, backing up their FA Cup win by reaching the top flight.

That summer, their beaten opponents Doncaster Belles and several other leading clubs stepped up to semi-professional status. But, by the following year, the professional dream was in tatters.

Phillip and Fulham swept aside all before them in 2002-03, their first season in the top flight, as they won a treble of league, League Cup and FA Cup, retaining the latter with a 3-0 win over Charlton.

But, in the same season, Al Fayed announced it would be Fulham's last as a pro team. With no other clubs having followed suit, it was no longer economically viable.

Having to return to juggling work, childcare, training and playing, Phillip's life became "very complicated".

"I found work as a play assistant, which I loved," says Phillip.

"I joined Arsenal in 2004, who were professional in all but name. The training there was as good as it had been at Fulham but you had to work in the day and train in the evenings."

Arsenal's semi-pro status was an improvement on Phillip's early England days in the mid-1990s.

"My first England shirt was an extra large men's shirt.

"I still have that and I look at it and I go 'wow, I was 18 and I pulled that shirt on'. I can't imagine what I looked like in it.

"The first time we had kit cut for us was at Arsenal. It was a female size 14 shirt. It was designed for us, which was fantastic."

Women's football was becoming less of an afterthought.

Arsenal were already developing into one of the greatest sides ever to grace the game in England.

And Phillip became a big part of it.

By the time she retired in 2008, she had played a key role in four of Arsenal's five successive league title-winning seasons, as well as appearing in three consecutive FA Cup final victories.

Arsenal were already developing into one of the greatest sides ever to grace the game in England.

And Phillip became a big part of it.

By the time she retired in 2008, she had played a key role in four of Arsenal's five successive league title-winning seasons, as well as appearing in three consecutive FA Cup final victories.

The crowning glory came in 2007 when Arsenal became the first British team to win the Champions League - then the Uefa Cup - and won every competition they entered.

"The FA Cup was the final part of the quadruple," says Phillip. "So there was real pressure. We went behind but beat Charlton 4-1."

Twelve months after Phillip won the Champions League, another fine footballer from Peckham did likewise.

Manchester United's Rio Ferdinand, born just a year after Phillip, had seen his talents recognised by the riches afforded to the best male players on the planet.

Ferdinand had commanded in excess of £50m in combined transfer fees and was one of the highest earners in the Premier League, where the average weekly wage had reached £30,000. Women, though, didn't even have the opportunity to play professionally.

The 2007 FA Cup final, in which Arsenal clinched the quadruple, was the first of two consecutive finals to be held at Nottingham Forest's City Ground.

A crowd of 24,529 in 2007 grew by a handful to 24,582 when Phillip and Arsenal beat Leeds 4-1 in 2008.

That figure remained a record until the final moved to Wembley in 2015, which was the making of the modern-day Women's FA Cup final.

A Women's FA Cup final at the national stadium allowed the FA to tie up what was, at that point, its biggest sponsorship deal as utility company SSE signed on.

More than 30,000 fans saw Chelsea beat Notts County 1-0, a figure which has risen nearly every year since, reaching a record of 45,423 as Chelsea beat Arsenal 3-1 in 2018.

Phillip's one-time 14-year-old Millwall Lionesses' team-mate Chapman became the first female captain to walk up the famous Wembley steps in 2015 when she collected the trophy for Chelsea, a feat she repeated in 2018 in her final match before retirement.

"Seeing Katie do that was extraordinary," says Phillip. "People ask me if I wish I had started playing 10 years later but the time you get is the time you get."

From success on the pitch to success in the dugout.

When the manager's job became vacant at her local club Peckham Town in the summer of 2019, the Kent County League side realised there was no-one better suited to the role than Phillip.

She had played at the highest level and knew as much about the club as anyone, having filled various coaching positions during a 20-year association.

In 2020, her first season, she led Peckham to their first-ever silverware.

Last August - in a final delayed by Covid - Peckham beat AFC Cubo on penalties to win the London Senior Trophy.

Phillip called on all her FA Cup final experience to inspire her players.

"I just told them these are the days you play for, the days you remember forever," she says. "Give your best, don't let the occasion pass you by. Leave everything out there. And they did.

"Taking my local club to their first trophy as a manager means as much as the FA Cups and England caps I won as a player."

Returning home after a kickabout with her friends outside Millwall's old Den and switching on the television to watch highlights of the Women's FA Cup final is Phillip's first memory of women playing football on TV.

Phillip sometimes wonders if life would have been different if she hadn't chanced upon that coverage of Millwall Lionesses beating Doncaster Belles 1-0 at Prenton Park.

"'Oh my days, it's Millwall, they're in a cup final, and they're women'. I just remember thinking that was incredible," Phillip recalls. "It's so true - visibility is key."

"If you don't see it, you can't be it."

The fact that she reached the age of 14 before catching a glimpse of people of her own gender playing football on TV shows how far away acceptance was.

From a total ban and being barred from men's grounds, to borrowing men's boots and having to wear hand-me-down shirts, the evolution of the women's game has been considerable.

Phillip embodies just how far it has come since that first FA Cup final in 1971, but also just how wide the inequalities remain.

Sitting, as they do, in the 11th tier of men's football, Peckham Town are one level below being eligible for the FA Vase, the FA's secondary cup competition for non-league men's clubs.

If they were to achieve promotion and go on to win it, the club would net £30,000 in prize money - that's £5,000 more than Manchester City Women collected for lifting the 2020 Women's FA Cup.

Progress has been made, but there's still work to be done.

Credits

Writers: Chris Slegg, Owen Phillips

Producer: Brendon Mitchell

Commissioning editor: Chris Osborne

Sub-editor: Mike Whalley

Images: Rex Features, Getty Images, The Football Association, Mary Phillip, Pat Chapman, Sheila Edmunds, Lori Hoey, Rob Avis - Avis Action Images, Gavin Powers Urban Prowler

Main graphic: Bex Grimble

Publication date: Friday, 7 May 2021