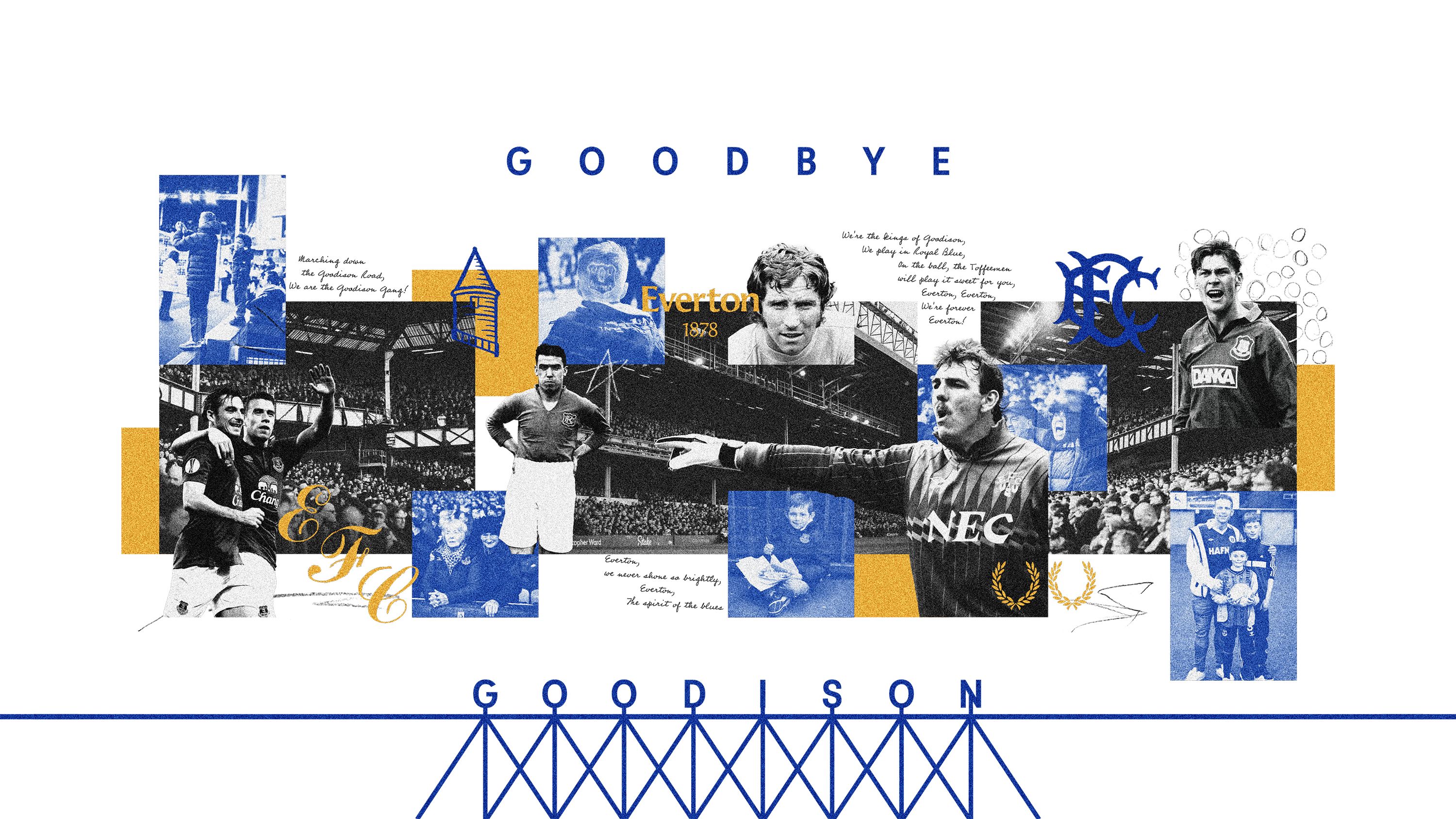

Goodbye Goodison

"Everybody used to stamp their feet, even for a corner. It was like a rumble of thunder, a roar of anticipation. Anybody who goes to the match and supports a club knows that excitement. It's hard to describe. It's just, 'yeah, this is where I belong now'."

Everton fan Frank Keegan's connection with Goodison Park - home of the Toffees for 133 years - stretches back more than a century.

His grandfather first started watching Everton play there after coming over from Ireland in the late 1800s. His father became a regular in the early 20th Century, and now Frank sits with his son Chris and five grandsons. Five generations of one family connected by a stadium built in the Victorian era.

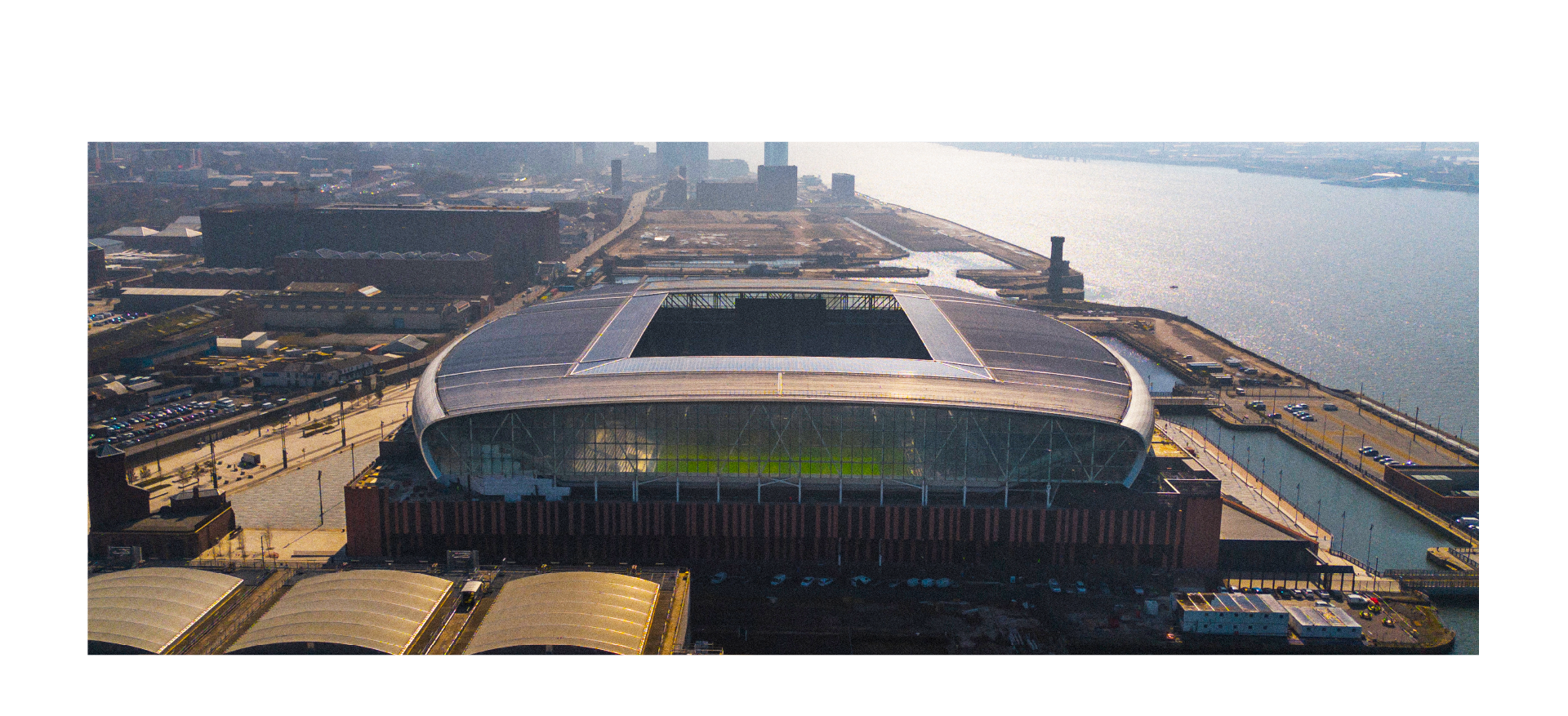

But now, with the men's team moving to their new ground on the city's waterfront at Bramley-Moore Dock, that connection will be severed for many. Although the stadium will remain, and from next season become the home of the club's women's team, new chapters in a story created over generations will be written two miles to the west.

Nicknamed the 'Grand Old Lady', Goodison is steeped in history. It was the first purpose-built football stadium in England and has staged more top-flight games than any other. It has also hosted FA Cup finals and internationals, including a World Cup semi-final. In 1924 it even hosted an exhibition baseball match between the Chicago White Sox and the New York Giants.

Its story is intertwined with Liverpool's growth as an industrial powerhouse during the Victorian Industrial Revolution, driven by the sprawling docks along the waterfront that at one stage saw 40% of the world's trade pass through it.

But as the 20th Century wore on and Liverpool's status as an industrial force declined, so too did Goodison.

"Goodison is now looking a bit worn and shabby, whereas I remember it being majestic," Frank told BBC Sport. "I'll be really sad, but I am excited about the new ground. I think the way football is, we've got to move on."

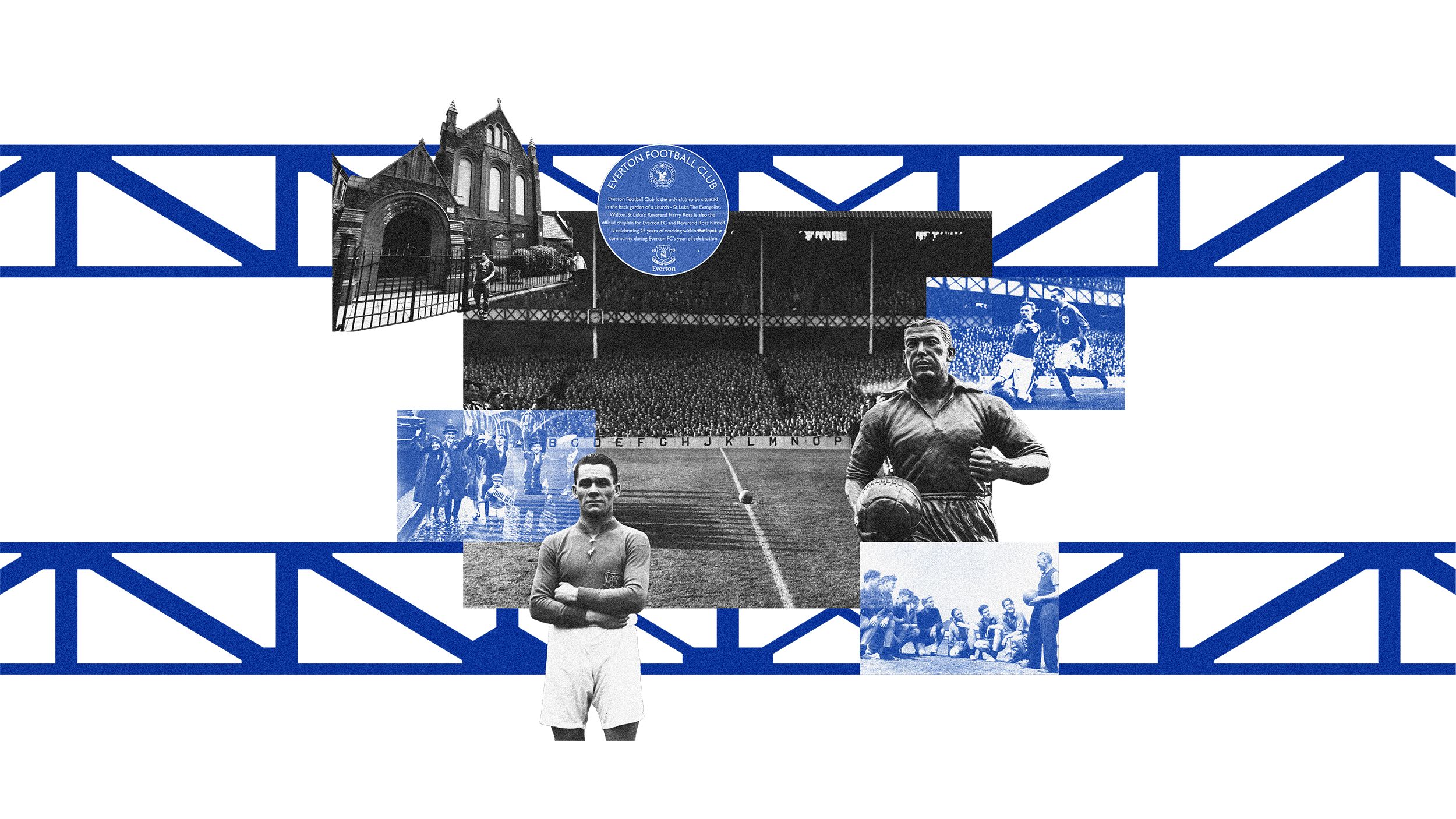

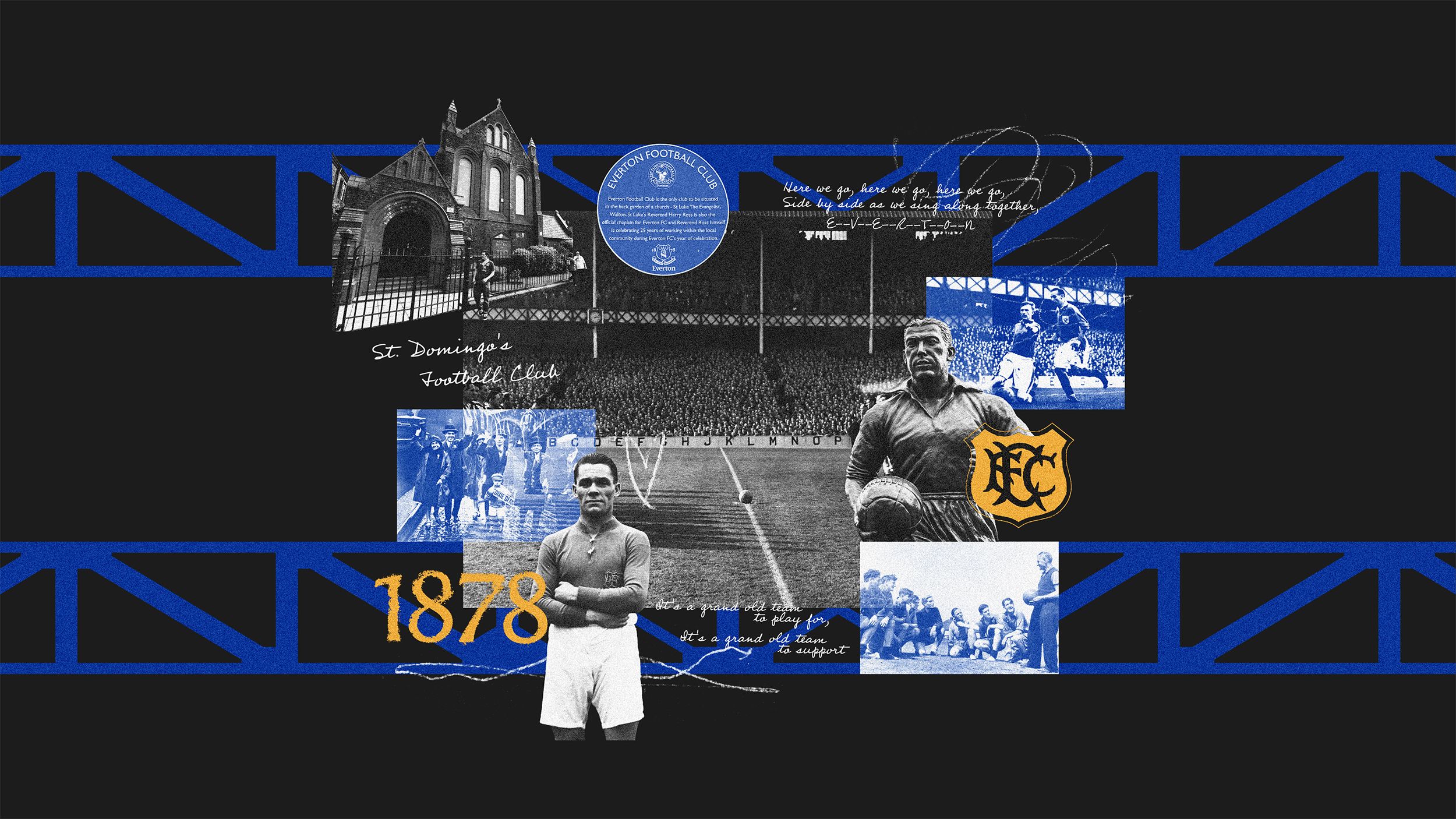

The beginning

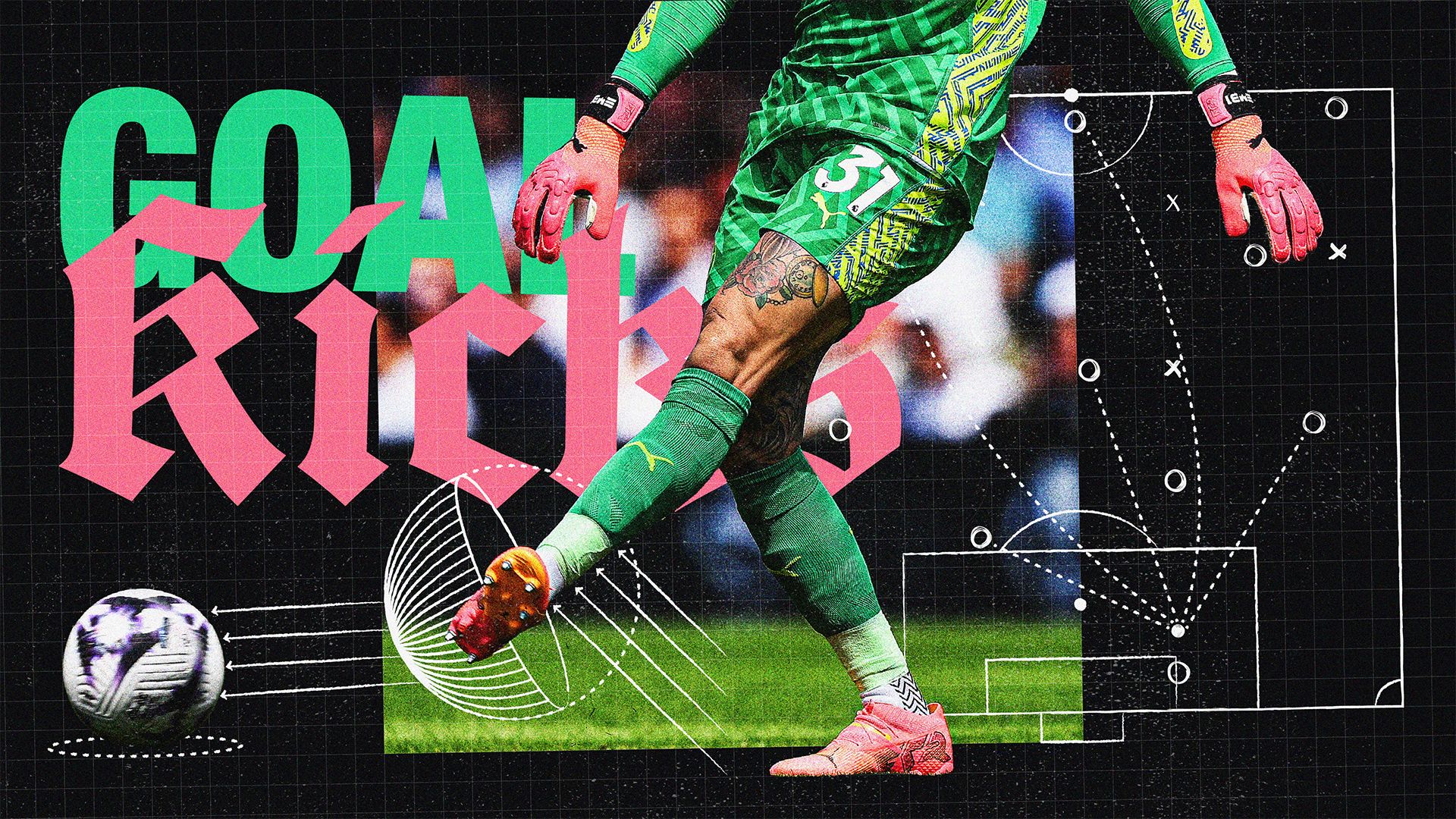

Everton were founded as St Domingo's FC in 1878, named after the nearby St Domingo Methodist Chapel, to give members of the congregation the chance to play sport all year round, not just cricket in the summer months. But as an empowered working class began to enjoy more leisure time, football also became a spectator sport.

"It was the people in the church trying to get the local village folk involved in sport to give them some good, healthy Christian exercise instead of being down the pub," Rob Sawyer, a member of the Everton Heritage Society - a voluntary group researching and chronicling the club's history - told BBC Sport.

"Within a few years, people would start to come and stand on the touchline at Stanley Park, where the team was first playing, and it soon caught the imagination."

The Toffees moved to Anfield in 1884, winning the first of their nine league titles there in 1891. But a dispute with landlord John Houlding saw the club move across Stanley Park to Goodison, with Houlding forming a new club - Liverpool FC.

Going to the match soon became a weekly ritual - red or blue - offering a distraction from the difficulties of everyday life, particularly during the docks' decline in the early 1900s, the trauma of two World Wars and the economic recession of the 1970s and 1980s.

'It’s your great escape, isn't it?" said Rob. "If you're somebody who's working a very hard 60-hour week on the docks, on a shipyard or in a factory, it was the great leisure pursuit, the great escape from the hardship of work.

"Then as the industry and maritime trade decreases, with high unemployment, it was again an escape from the doldrums that you might find yourself in, and brought some pride to the city.

"There was always that connection with the fans, who were from predominantly, but not entirely, a working class background, in the areas of Anfield and Walton and the wider north Liverpool area. Those areas saw a lot of hardship, but you've got these two beacons of light [ Everton and Liverpool] divided by the park."

Like Frank, Sawyer also has deep links with Everton. His great grandfather Bob Sawyer was club secretary towards the end of World War One and later joined the board. His grandfather Bill Jr founded the Everton Supporters Federation.

"I have been going to Goodison for more than 40 years, so it's that connection to the people who go with you. I went with parents knowing that my grandparents and great grandparents have been there.

"With my great granddad and my granddad being involved with the club in different ways, I take pride in the links they had to the ground every time I set foot inside Goodison."

'One of the finest in the land'

Reminders of Everton's history are everywhere you look. At the Park End sits the imposing statue of Dixie Dean, a legendary forward who scored 383 goals in 433 appearances for the Toffees, including a record 60 league goals in the 1927-28 season.

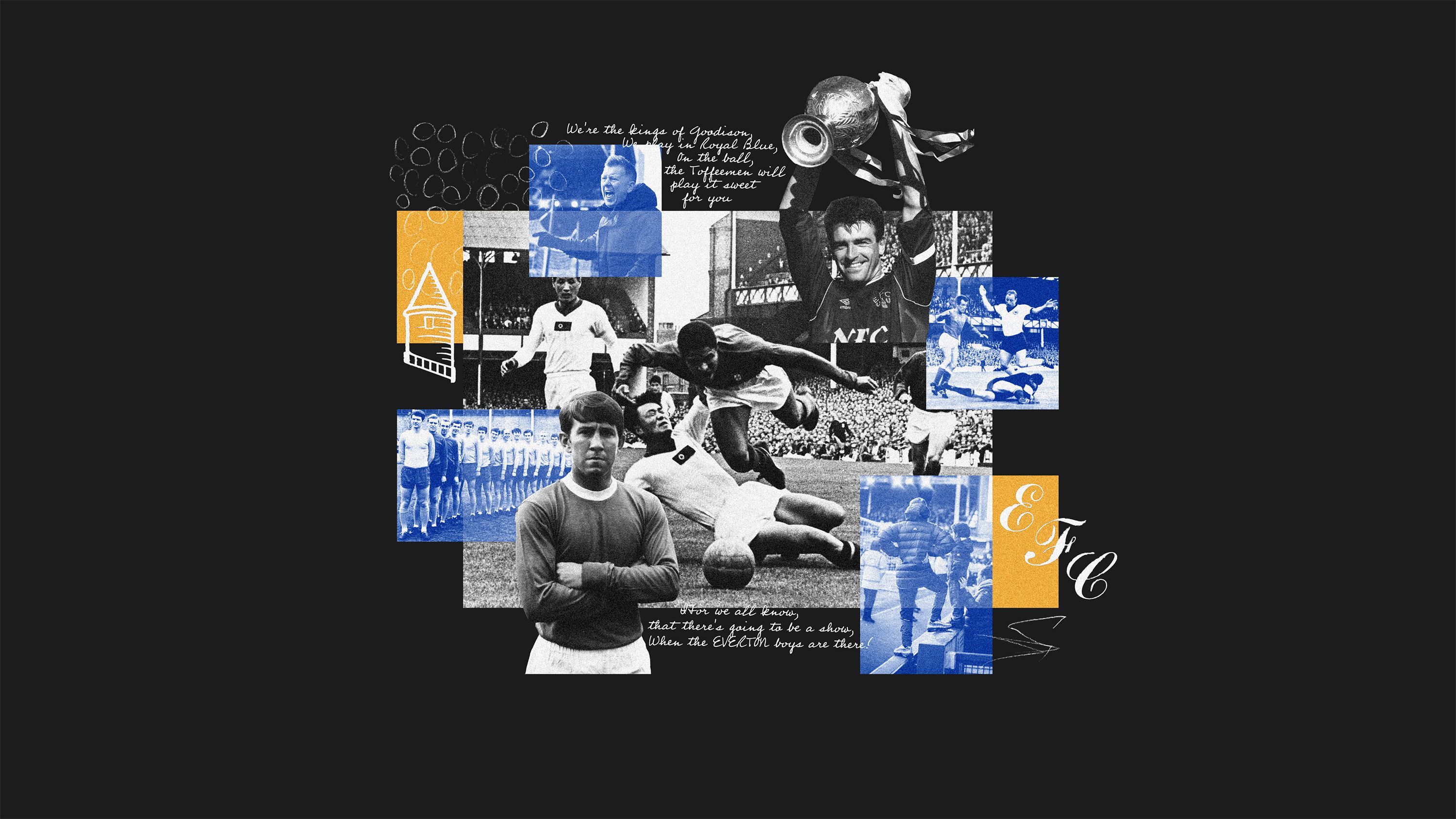

At the other end of the ground is Everton's 'Holy Trinity' - Howard Kendall, Colin Harvey and Alan Ball - who were central to Everton’s 1970 title-winning side. Kendall would go on to become the club's most successful manager, winning two league titles, an FA Cup and a European Cup Winners' Cup during the mid-1980s.

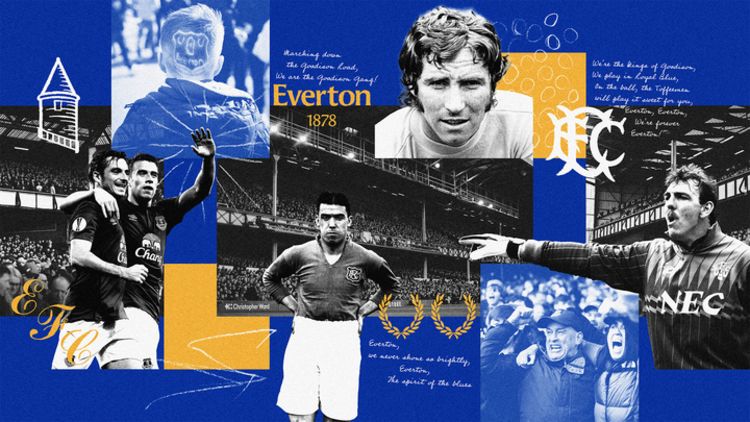

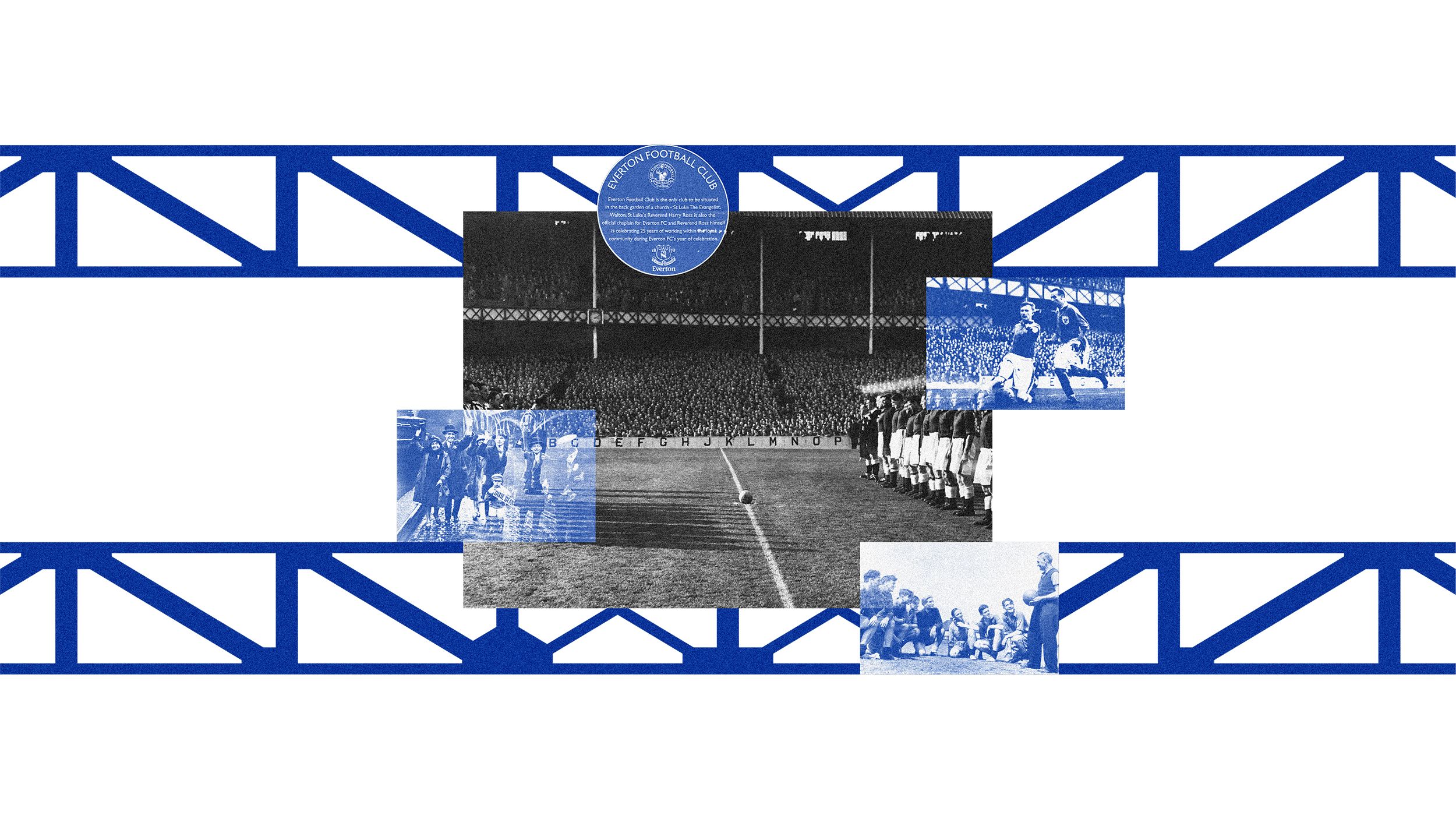

The Bullens Road and Gwladys Street Stands, completed in 1926 and 1938 respectively, still bear the trademark latticework design of renowned Scottish architect Archibald Leitch, who designed some of Britain's most famous football grounds at the start of the last century, including Rangers' Ibrox, Celtic's Celtic Park, Scottish football's national stadium Hampden Park - all three in Glasgow - and Manchester United's Old Trafford.

A photographic timeline featuring iconic images of Everton's past stretches round three sides of the ground. It also features an image of the 1966 World Cup semi-final between Franz Beckenbauer's West Germany and Lev Yashin's Soviet Union.

Goodison hosted five matches at the tournament, more than any other club ground, including Pele's Brazil against Eusebio's Portugal in the group stage.

"It was widely regarded as a pioneering ground and also one of the finest in the land. That continued beyond World War Two and very much into the 1960s," said Sawyer.

"Eusebio would go on to say that it was the greatest stadium he has played in. That says everything about Goodison at its peak."

The people and the memories

Goodison is not just players, grass, bricks and mortar. It is also about people. The matchday ritual. Walking up streets of tightly spaced Victorian terracing; meeting friends and family by Dixie's statue; chips at the Goodison Supper Bar; a pint in the Winslow Pub in the looming shadow of the triple-decker Main Stand; perusing the memorabilia, old programmes and vintage shirts upstairs in the Church of St Luke the Evangelist, home of the Heritage Society, which is nestled between the Gwladys Street and Main Stand.

"I started going every week in late 1961. My mother said I had to follow my dad and be an Evertonian. I was dead excited to go," said Frank.

"I started going with a lad I used to play with at the end of the road and his dad. They had a minivan and they'd come round to our house and pick me up with about four or five other people, all packed in the back of this van.

"The first sight of the ground was the floodlight pylons, then getting up close to it, it was the sheer amount of people, the excitement of it.

"When people move house there's some memories that you leave behind. But you can also take memories with you, and I'm just going to try and do that as much as I can."

For Chris Keegan, it is that sense of belonging that makes going to the match so special.

"Some of the best days of my life have been at Goodison," he told BBC Sport. "With my dad, with friends. And it is the fact all my boys go as well, the seven of us together.

"But it is also the people around you. The guy who sits behind us with his grandson has sat there since 1968, he must be in his 80s. There's another guy who has sat in the same seat with his son since we first started sitting in our seats. There was a fella behind my dad, Albert, he was going well into his 90s. Unfortunately, he's passed away now. But you remember these people."

Rising from the ashes

The emotionally-charged decision to let go of the past to embrace the future is a familiar one in English football. Eight of the 20 Premier League teams have moved to new stadiums in the past 25 years, including the London trio of Arsenal, Tottenham and West Ham. In March, Manchester United announced plans to knock down Old Trafford and build a new stadium, while Newcastle are considering leaving St James' Park for a new ground in nearby Leazes Park.

Leaving will not be easy, but Evertonians reluctantly accept they have to move.

Proposed moves to the outskirts of the city or retail parks were fiercely resisted, but the fans have embraced the opportunity to move to the waterfront and reconnect with the city's industrial past.

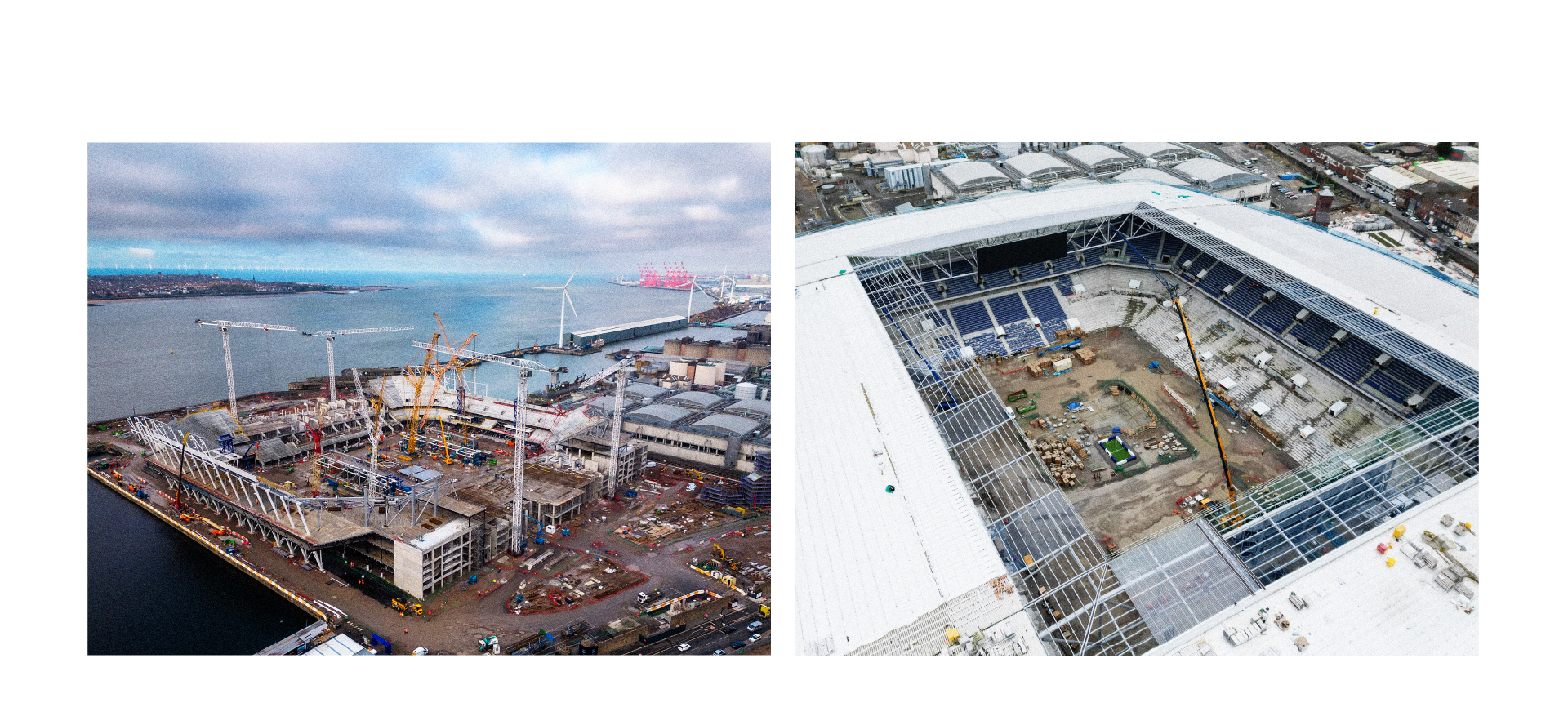

Over the past four years Everton have taken the disused Bramley-Moore Dock and turned it into a spectacular arena. It has everything a modern stadium needs - stunning views, corporate spaces, the ability to host concerts and other events all year round.

But the club has also acknowledged the area's past. Heritage aspects of the site, including the Grade II listed hydraulic tower and engine house, built in 1883, and the old dock railway track, have been restored.

"The derelict dock, that hasn't been used since about 1988, was very much representative of the decline of not just the city but the wider de-industrialisation of the north," said Rob.

"It's almost like Everton rising from the ashes a bit and also the city of Liverpool itself. Without sounding dramatic, it is a sort of rebirth."

Running along the South Stand of the stadium will be 'Everton Way', a line of personalised engraved stones purchased by fans, many including names of people who have passed away.

It is a reminder that not every Everton fan will be making the move from Goodison.

"It's hugely emotional, isn't it? The connection and memories with people no longer with us, like my great grandfather, grandfather, both my parents and my sister. It's going to be very hard to leave behind those first-hand shared memories of being in there," said Rob.

"We've all had hard times in our lives but Goodison was a place of sanctuary and happiness. So when it comes to the last day, I'm a bit in denial. But it's becoming, very, very real."

For Frank, the day Everton's men's team leave Goodison will be tinged with sadness, but it is something he feels they have to do.

"It's been my life going there," he said. "I look across from my seat to the Lower Bullens and the Upper Bullens Stand and you see ghosts of your mates that used to go to matches.

"But another part of me thinks that the Goodison Park I remember growing up, as a ground, went a long time ago. We've got to move with the times.

"But it's not about me, it's about individual supporters. You've got your memories of the ground, but the ground is just a place that held them. And you can think back and remember them fondly."

Credits

Words by Tom Mallows

Subbed by James Standley

Design by Andy Dicks

Images by Getty & Adam Rosenbaum