Olympic fencer and model champions body positivity

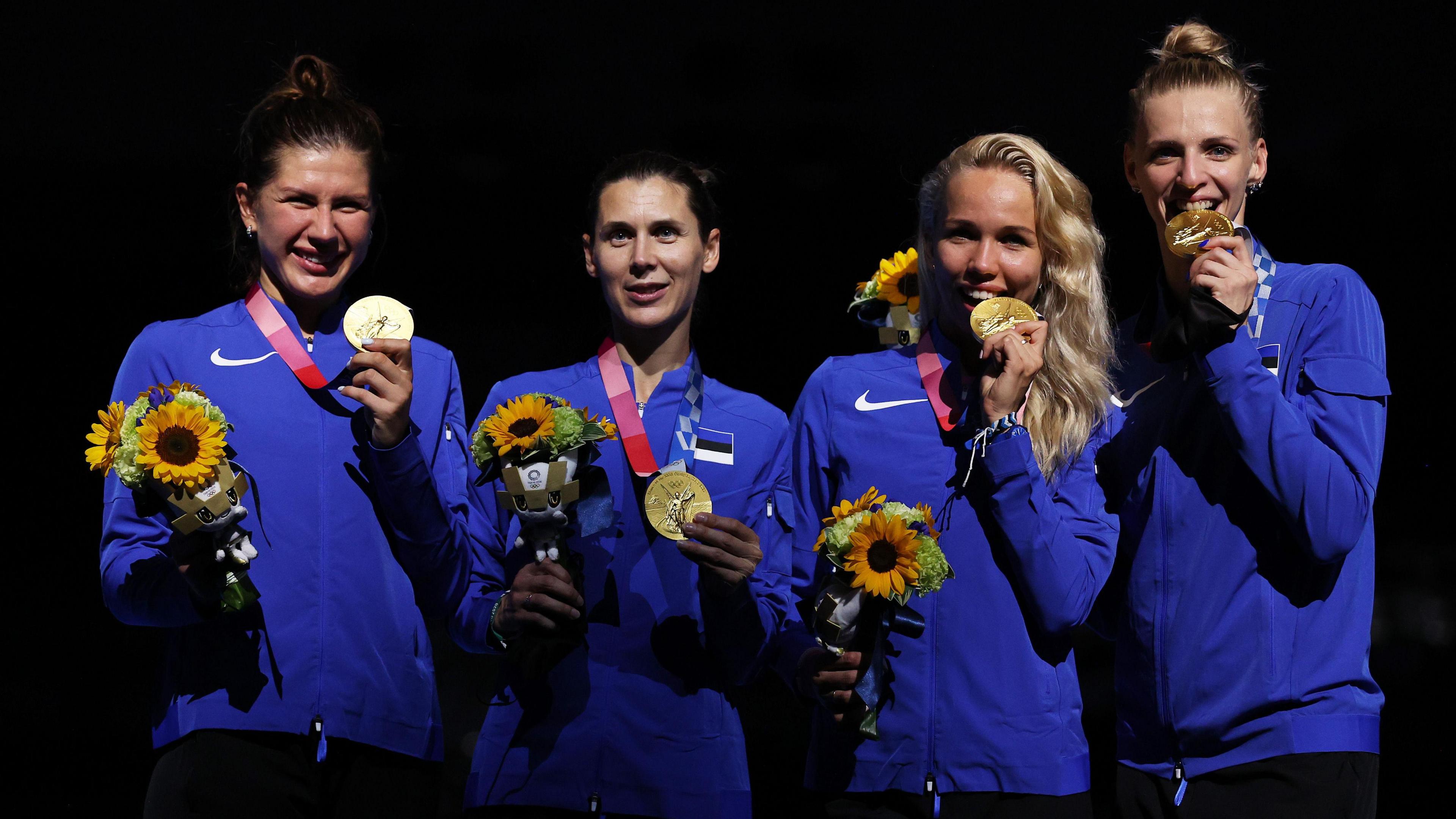

Kenyan fencer Alexandra Ndolo won silver at the 2022 World Fencing Championships when representing Germany

- Published

Not many athletes have switched from competing for Germany to Kenya, but then Alexandra Ndolo – a former military veteran-turned-model who is eyeing Africa’s first Olympic fencing gold medal – is not one to take the easy option.

Add in the fact that she’s trying to perform well enough in Paris to ensure she receives funding from Kenyan authorities to continue competing, and it’s clear the 37-year-old has plenty to focus on as her childhood Olympic dream finally materialises.

The first Kenyan fencer to compete at the Olympics, she will take to the piste in epee as a serious contender, having won a World Fencing Championships silver medal for Germany in 2022.

Just two months later, she stunned many by switching allegiance to Kenya in honour of her late father, who was raised in the East African nation.

“I feel like even when it has been hard, he's with me every step of the way,” Ndolo told BBC Sport Africa.

“I know he would be proud of me, and [I believe] he's watching.”

Africa has won just two Olympic fencing medals, with Egypt’s Alaaeldin Abouelkassem taking silver in 2012 in the men’s individual foil before Tunisian Ines Boubakri won bronze in the women’s foil four years later.

“I don't see it as a burden, I see it as a chance to bring some joy and pride to the continent,” Ndolo said.

Ndolo – who also has a silver and bronze from the 2017 and 2019 European championships respectively – also wants to shine in order to spread a message dear to her heart.

Having suffered as a mixed-race girl growing up in Germany, Ndolo is desperate to boost body positivity among the next generation with African roots.

“I hope that I will reach an even bigger audience with the Olympics – and that I will inspire not just East African black and brown girls, but black and brown girls all over the world.”

Identity issues

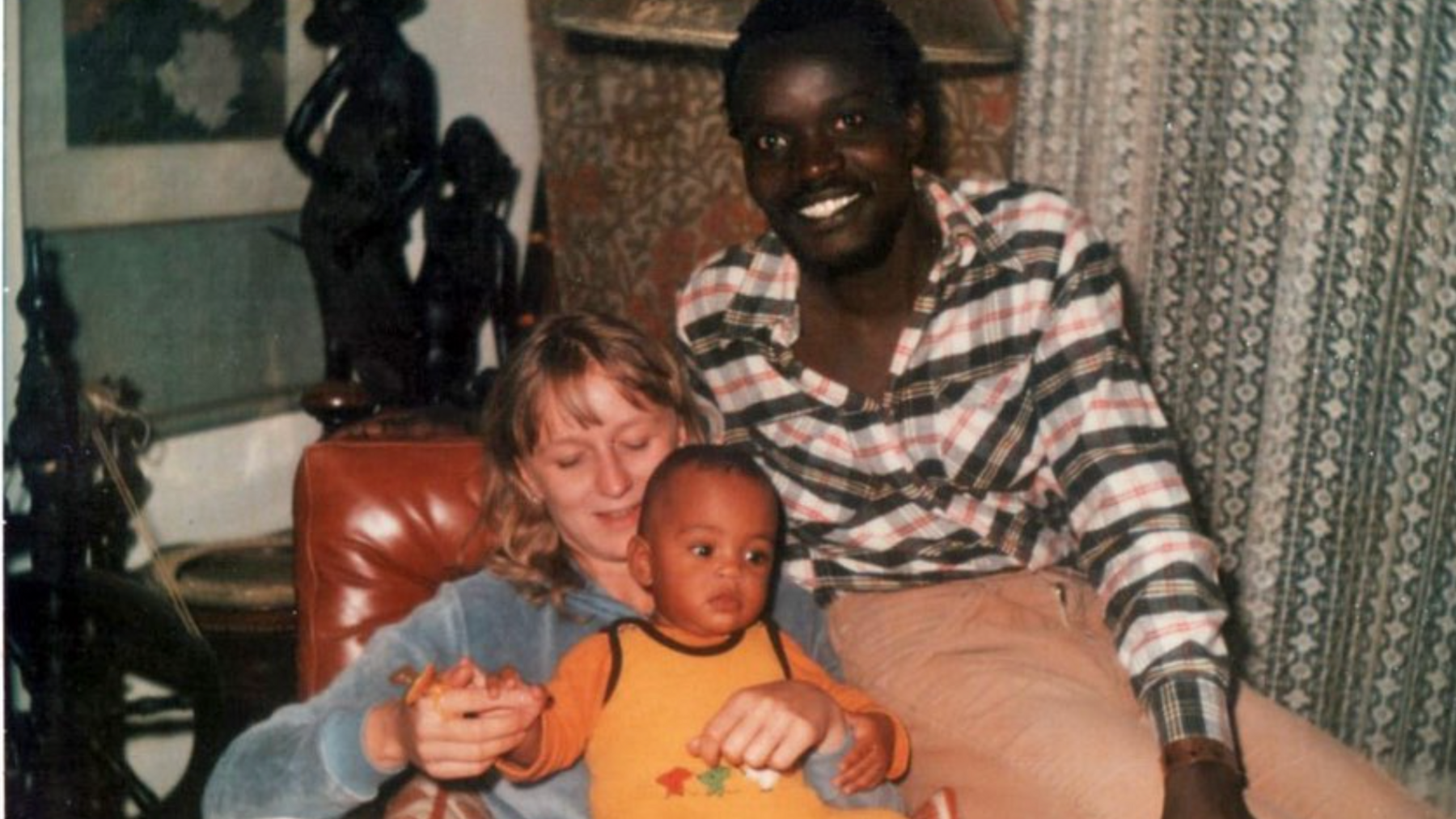

Born to a Kenyan father and a Polish mother, Ndolo grew up in a conservative town in Germany

When Ndolo appeared on the front cover of the Playboy Olympic magazine for Tokyo 2020, as a woman proudly displaying her African roots it was a major stop on an ongoing journey.

For growing up with a white Polish mother and an African father in a country where neither had roots, Ndolo found herself considering her identity early on.

Seen as a black woman in Germany but often identified as white in Kenya, she has long struggled to escape the beauty standards projected on her by the two cultures she inhabits.

“In Kenya, we have a beauty standard with more curves so I might be not slim enough for the European beauty standards and not curvy enough for the Kenyan beauty standard,” she explained.

“That's where I'm like: ‘Can we just accept our bodies the way they are?’”

Ndolo says she started experiencing body shaming as she reached her teens in Germany, when she realised she did not have a popular look with the boys while some girls badly bullied her.

“They were zooming in on my hair, my skin, the shape of my nose – it was basically an everyday campaign for a whole school year, telling me that I was not pretty.”

Hair raising

Ndolo has been posting revealing photos online - in an 'artistic way', she hopes - in a bid to boost body positivity amoung younger women

Two decades on, Ndolo became the first black athlete to appear on the Playboy Olympic cover.

During the shoot, she insisted on having her hair natural – as many Africans would have – and not straight.

“I made the conscious decision to have my hair curly,” she recalled.

“I wanted young adult women to see someone looking just like them on the cover of such an important magazine. I want black women in general to know they are beautiful just the way you are.”

“I want them to know it's not important what the Western world might think is beautiful and that they don't need to chemically change their hair or skin to be lighter to be beautiful.”

“Your body is not a trend, it should never be a trend.”

Playboy aside, Ndolo has also posted nude photos on social media, in what she hopes is an artistic way, as she continues her messages of empowerment.

She has received her fair share of negative comments but, after 11 years in the Germany military, has the mental resilience to ride it out.

“I do it because I want other women to see that body positivity in an African sense exists, and I'm so happy when I get messages from women thanking me for representing them.”

Kenya believe it?

Ndolo won her second successive African title in Morocco earlier this year

The military drills Ndolo undertook over the years also helped her adapt to the 2022 switch from the relative pampering and lifestyle of a European athlete to the financial hardship of an African one.

“I left this really strong, secure German support system where basically I just had to come with my bags packed to the airport and everything was ready,” she explained.

“That's very different to my situation now because I'm booking everything, with my mum and I paying for 99% of the things. There were some nights I was really crying and [wondering] how to get through the next month.”

She estimates that it has cost at least $50,000 (£38,700), most of which was provided by her mother, to qualify for Paris 2024.

“We said she’ll help me until the Olympics but afterwards things need to change because I can't keep going like this – you can't ask your retired parents to pay to raise the Kenyan flag.”

Whether or not she medals in Paris, there seems every chance she will leave a mark on Kenyan fencing.

“I would like to have a fencing club in every county and want to see fencing in high schools and universities,” said Ndolo, who would also like to see fencing integrated into the Kenyan army.

A founding member of Kenya’s fencing federation in 2019, Ndolo has helped open fencing schools in the capital Nairobi, where some athletes receive scholarships to study coaching courses in South Africa.

A Kenyan gold in Paris would push the sport even further.

“I want to be remembered as a trailblazer. I can't wait to raise the Kenyan flag high.”

Related topics

- Published22 May 2024