Euro 2000: The French Revolution

- Published

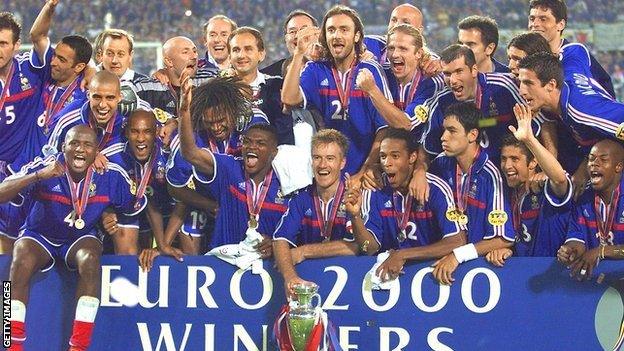

Euro 2000 was awash with orange, but ultimately the tournament was all about Les Bleus.

The streets and stadiums of the Netherlands, co-hosts along with Belgium, were dominated by the brightly adorned hordes of the Dutch Oranje Army, but on the pitch Roger Lemerre's France were dominant.

Having won the World Cup on their own turf, external two years previously, the French came into Euro 2000 with a single aim: to set a football precedent by adding the Henri Delaunay Trophy to their global crown. They did not disappoint.

Former Arsenal, Barcelona and Chelsea midfielder Emmanuel Petit, a prominent member of the French squad at the turn of the millennium, told BBC Sport: "Euro 2000 was a big target for us because it meant we could print our name on football history.

"Winning the World Cup is a huge achievement, but when you can complete the double you can put your name in the football hall of fame. We wanted to make history."

France's Euro 2000 squad was stronger and more experienced all-round than their World Cup-winning one, built around Laurent Blanc, Marcel Desailly and Didier Deschamps and the excellence of a peaking Zinedine Zidane.

In 1998, it was widely accepted Aime Jacquet succeeded without a world-class striker at his disposal, but two years later Lemerre had three to choose from - Thierry Henry, David Trezeguet and Nicolas Anelka.

"We had unity. We were all connected. We had knowledge from the players in terms of movement and how to adapt in different situations. There was solidarity between us," explains Petit.

"If you look at the first XI at that time, I suppose eight of those players were the best in the world in their position. But it was all about the team, not individual players.

"One of the most important things was the players in the squad played for some of the biggest clubs in Europe, so we got used to the pressure and the expectations - it gave us the strength mentally to reach our targets.

"Everything was in place at the right time to give us a chance to win the World Cup and then Euro 2000."

On home soil in 1998, France hoped for success, but in 2000 it was expected. This was something the squad had to shoulder and, as Petit explains, ultimately turned to their advantage.

"We had a strong pressure on our shoulders but it was also a good pressure," he said.

"All the French people wanted to make history so we felt their wind at our backs. We were given their love, which is one of the strongest things they can do for us."

Euro 2000 was a tournament that deserved a quality winner.

Major international football events very rarely live up to the hype - but this delivered in full, as attacking philosophies largely came to the fore in a flurry of goals and entertainment.

There were poor teams but very few poor games.

England and Germany were two of the worst on show. The former, led by Kevin Keegan, registered a rare victory over the latter in a dour encounter in Charleroi,, external but both deservedly failed to make it beyond the group stages.

Portugal beat both en route to a semi-final exit at the hands of the French and were rightly applauded for their attacking intent, as were Yugoslavia, whose accompanying defensive frailty was ruthlessly exposed by arguably the tournament's real flair side, the Netherlands, in a blistering six-goal display in the quarters., external

The Dutch side and their fervent support lit up the event, and they were the only side to beat an admittedly weakened France, external in the competition, but their seemingly relentless journey to the final was halted by a semi-final penalty shoot-out defeat to Dino Zoff's methodical Italy,, external who then came within a whisker of ensuring pragmatism ultimately won out over flair.

However, it would be wrong to vilify the Italians, whose defensive organisation demonstrated a different kind of admirable beauty and heroism, especially in the semi-final, when they successfully repelled the potent attack of the home nation with 10 men for effectively 90 minutes including extra-time following the dismissal of Gianluca Zambrotta after 34 minutes.

The football in the final, external was not quite as brilliant as much of what had gone before, but it was certainly breathless and the conclusion was pure drama.

With 90 minutes played, Italy looked set for glory thanks to Marco Delvecchio's 55th-minute finish, but France would not be denied and substitute Sylvain Wiltord struck to send the game to extra-time, during which David Trezeguet rifled in a golden goal to ensure France's place in football history.

"I thought we were going to lose that game," admits Petit, who was forced to miss the match through illness.

"Our experience helped us a lot. When you're losing 1-0 to the Italians you know they are going to close up the game and it is end of story. But because we were used to playing under such big pressure and some of the players at that time were playing in Italy as well, we were able to keep our nerve.

"I think the Italians dropped off a little bit. They thought they were winning the tournament, but obviously the game is not done until the whistle is made."

When the whistle was decisively blown in Rotterdam, it heralded the right result as a glittering golden goal provided a fitting finale for one of the most colourful tournaments in living memory.

- Published17 May 2012

- Published12 May 2012

- Published12 May 2012

- Published12 May 2012

- Published12 May 2012

- Published12 May 2012

- Published12 May 2012