Why are fans staying away from Brazil's championship?

- Published

- comments

A month or so ago I was making my way back on the train after a game involving Rio de Janeiro club Fluminense when I overheard a supporter talking about the death of his father a few months earlier.

His dad had passed away on the same day that Fluminense faced Boca Juniors of Argentina in a big game in the Copa Libertadores, South America's Champions League.

Despite that, said the fan, "I still went to the game. It's what he would have wanted. My dad was a fervent Fluminense fan. I could imagine him saying "son, it's too late to do anything for me, but you can go and give the team a hand."

The story, which I shall retain and roll out the next time someone tells me that football does not matter, illustrates the depth of the bond that exists between the fan and the club, the individual and the collective.

I feel sure that this fan (and spiritually speaking, his father) was present in Rio's Engenhao stadium for Fluminense's home match on Sunday - as long as he was able to get a ticket. Supporters queued for hours last week to ensure their presence for the match against Cruzeiro - even though there was nothing resting on the game.

Away to Palmeiras the previous week, an 88th-minute goal by centre-forward Fred had given Fluminense a 3-2 win and ensured,, external with three rounds left to play, that the title was coming back to Rio. Sunday's game against Cruzeiro, then, was little more than a giant celebration.

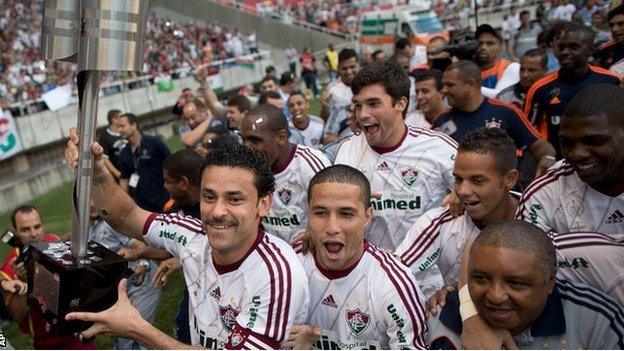

It hardly mattered that the hosts lost 2-0. The match was no more than a 90-minute prelude to receiving the trophy and performing the lap of honour. It seemed that every Fluminense fan wanted to be there.

It is a shame that they were not always quite so keen to turn up during the course of the campaign. Before the Cruzeiro game Fluminense's average home crowd had been just over 12,000, a few hundred below the (very disappointing) overall average for the Brazilian Championship.

The full house for Sunday's game is evidence for the view, expressed to me by many insiders, that Brazilians are more interested in victory than they are in football. Andre Rizek, presenter of a local TV show on which I make regular appearances, argues that Brazil's national sport is cheering the winners.

It would be simplistic to isolate one reason for the fact that crowds in Brazil are lower than those in the United States Major League Soccer. Specifically in Rio there is the issue of the Engenhao stadium, which will play host to the athletics in the next Olympics. It is unpopular and seen by many as poorly located. Crowds will increase once the Maracana (and other 2014 World Cup venues around the country) are ready.

But this is far from the only issue. Sao Paulo FC, for example, have a huge stadium, the Morumbi, which on Sunday attracted the biggest crowd of the entire campaign - some 62,000 watching them clinch their Libertadores place with a 2-1 win over Nautico.

But before that their home average was just over 22,000. I was present for their first home game of the campaign, which less than 10,000 paid to see. In a giant bowl of a ground with no roof (one is being constructed) the atmosphere was like a reserve game.

The calendar is badly organised, the cost of tickets has risen too much, pricing many out of the game, and people of all income levels are preferring to watch the games on TV either at home or in bars. The timing of games does not help - 21:50 at night is too late and in the big cities, 19:30 on a midweek evening is too early.

But for all the blame that can be heaped on the organisation and the facilities, the mentality of the fans themselves is also part of the problem.

The previous game at the Engenhao stadium featured a Botafogo side who are really showing promise. Clarence Seedorf, external has been successfully assimilated into the team, and his presence is proving inspirational to an exciting group of youngsters.

Left-footed centre-back Doria, just turned 18, is an exceptional prospect, young midfielders Jadson and Gabriel are interesting and recent signing Bruno Mendes, a teenage centre-forward, has made such an impact that he is being compared to former international star Careca.

At the time of the game, at home to Portuguesa, Botafogo's late season surge had put them in with a slight chance of grabbing a spot in next year's Libertadores. But just 3,870 turned out to watch them - and many of those were mainly concerned with yelling abuse at the coach. It is hard to find a justification for a crowd figure that low.

I questioned a veteran journalist and a staunch Botafogo fan about it when we did a TV programme together on Sunday night. His explanation, apart from complaints about the stadium, was that Botafogo fans are tired of not competing for titles.

There are two possible answers to that; one is that the support given now can help consolidate the team as it builds towards fighting for trophies next year. The other is that winning is not the only, or even the most important thing. Football is all about feeling represented by your club - win, lose or draw.

I get the feeling the Fluminense fan I overheard on a train (and his late father) would probably agree. Brazilian football should clone him.

Comments on the piece in the space provided. Questions on South American football to vickerycolumn@hotmail.com, and I'll pick out a couple for next week.

From last week's postbag;

Why does Conmebol (the South American Confederation) decide to schedule Copa Libertadores matches for Wednesdays and Thursdays, as opposed to the Tuesday/Wednesday schedule favoured by UEFA for the Champions League? Myles Rivera Flam

You are slightly misinformed. Libertadores matches are scheduled from Tuesday to Thursday. The reason for this is that the main source of income is TV money, and so there are staggered kick off times to ensure that TV gets maximum return from showing all (or nearly all) of the matches to all of the continent.

I'd like to ask you about Edinson Cavani, the Uruguayan and Napoli striker. Having seen him in a few games, especially last year's Champions League and this year's Europa League, he seems a force to be reckoned with, and yet he still doesn't play in a top European team. What do you think is the reason behind that? He also doesn't seem as comfortable with Uruguay. Roberto Branca

Perhaps his experiences with Uruguay help explain why he's happy at Napoli. With the need to accommodate Diego Forlan and Luis Suarez for his country, Cavani has most often been used as a wide player, frequently dropping back into midfield. He'll do it - he is by no means a selfish player - but it takes him a long way from where he wants to be, which is as close as possible to the opposing goal.

In midweek against Poland Uruguay dropped Forlan, and Cavani shone in his favourite position, scoring one and forcing a Polish defender to turn another into his own net. But the years spent playing second fiddle with his country must make his Napoli status as top dog all the more enjoyable.

Tim Vickery is a regular guest on BBC Radio 5 live's World Football Phone-in, which is available to download as a podcast.

- Attribution

- Published26 September 2012

- Published11 August 2012